di Clovis WHITFIELD (with english text)

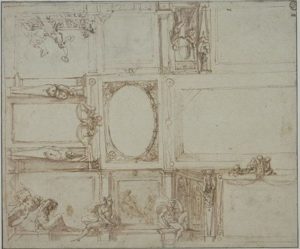

Ci sono molti esempi di disegni che sono stati spostati ad Annibale nell’attribuzione, e soltanto una completa revisione dell’opera grafica renderà possibile individuare le varie identità artistiche dei molti che frequentavano la bottega dei Carracci. Però questi disegni a penna e inchiostro potrebbero essere la chiave per capire il ruolo di Agostino, dal momento che molti di essi sono dedicati ad elementi architettonici, e sembrano come fuori scena oppure accennano ad una composizione generica. Per contro, gli studi dal vero di Annibale si preoccupano di rappresentare figure individuali, con un’eccezionale maestria nel realizzare il chiaroscuro ottenuto con carboncino e lumeggiature di biacca, e raramente hanno un margine definito. Questa divisione ricorda quanto riferito da Cavedone quando spiega l’accordo sul ruolo artistico che i due fratelli avevano stipulato: se Annibale era la star, tuttavia aveva bisogno del fratello per definire lo spartimento della volta, e che sempre Agostino gli fornisse l’impianto e la divisione spaziale e architettonica dell’intero spazio della volta. In seguito all’elogio che aveva ricevuto per le cariatidi di Palazzo Fava, si può dire che Agostino usò tutta la sua inventiva per giungere alla realizzazione di un’incredibile varietà di pose per queste figure portanti, che poi costituiscono la maggioranza della volta Farnese.

In esse ci sono citazioni dall’antichità della collezione Farnese, e si potrebbe ben affermare che fu lui il responsabile di questa ricerca iconografica che è invece di solito attribuita a suo fratello. Le fonti ci danno l’impressione reale che Annibale avesse poca urgenza di studiare in questa direzione: fu Agostino a visitare per primo Roma (all’incirca nel 1581) quando suo fratello stava ancora a Bologna. Ciò è perfettamente in linea con la grande familiarità di stili diversi che frequentò, essendosi confrontato con molti altri artisti di altre scuole e avendo inciso i loro lavori, un tipo di esperienza che portò al riconoscimento di quello che più tardi sarebbe stato chiamato l’eclettismo dei Carracci. Malgrado il famoso poema che celebrava Niccolò dell’Abate sia stato molto ridicolizzato per l’idea di un incontro/miscuglio di culture che per tanto tempo è stato associato con i Carracci, a loro svantaggio, noi faremmo bene a ricordare come la curiosità di Agostino per altre culture e stili fu il segno distintivo della riforma dei Carracci, qualcosa che portava ben oltre la solita tradizione della bottega di famiglia. I disegni giunti fino a noi non offrono l’idea completa della relazione simbiotica che esisteva tra i due fratelli, illustrando di contro il modo in cui funzionasse la loro collaborazione, perché il disegno finale spesso dimostra la creatività indipendente del pennello di Annibale, che aveva bisogno di guida e contenimento ma non tanto della preparazione. Il tipo di indagine stilistica intrapresa da studiosi come Ann Sutherland Harris e Diane de Grazia è vitale perché sta mettendo ordine, partendo dalla confusione che esisteva almeno dall’inizio, ad alcune delle caratteristiche dei loro stili.

Molto spesso questi disegni, se hanno un soggetto che si riferisce a dipinti reali, si possono riferire come “prima idea” ad Agostino ritenendo che una posa diversa entri in gioco in altri studi e siano da mettere in relazione solo indirettamente con il prodotto finito della Galleria.

Certamente non è sufficiente sottolineare la preferenza di Agostino per la penna e l’inchiostro, perché ci

sono anche disegni a carboncino, che è invece il medium preferito da suo fratello, e molti esempi dove il suo uso dell’acquerello è abbastanza libero. A poco a poco comunque alcuni disegni sono stati recuperati, come la maggior parte degli studi per la Tazza Farnese, e lo stile grafico del fratello maggiore è stato molto meglio definito, soprattutto grazie alle ricerche di Ann Sutherland Harris. Un gruppo importante, intorno a una tarda incisione di San Girolamo, dà un’idea chiara dei suoi tentativi ripetuti per arrivare a una invenzione adattabile, e questa reiterazione è evidente anche nei disegni per gli affreschi del Palazzo del Giardino in Parma, principalmente quelli per la figura di Galatea. Non è questo il luogo per provare a rivedere l’intera gamma di studi che sono stati probabilmente attribuiti in maniera erronea, ma possiamo però almeno dare un’occhiata ad alcuni di questi per cercare di avere un’idea più precisa.

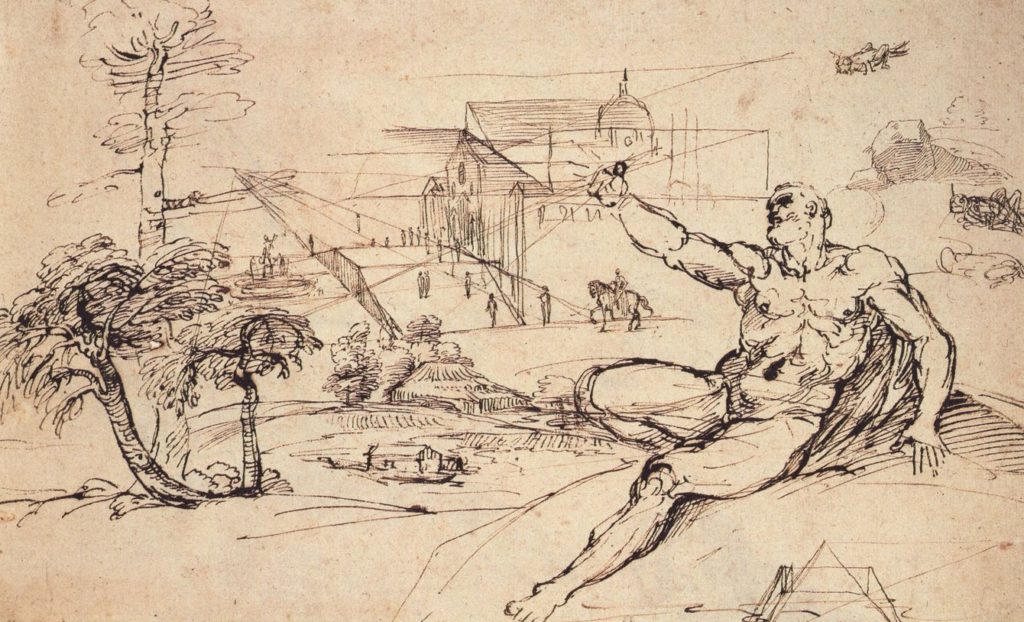

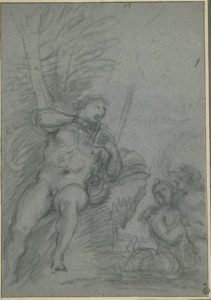

Il foglio del Louvre (Inv. 7210, Loisel n. 470) con alcuni studi per la Morte di Ercole, presente su uno degli architravi del Camerino, forse perché molto vicino alla sua realizzazione ad affresco, è stato a lungo considerato uno studio di Annibale e, tra l’altro, di particolare interesse per la presenza del paesaggio e degli schemi prospettici. Questo trattamento dell’anatomia è però estraneo ad Annibale, ed alcune caratteristiche come le cavallette, le rocce sfaccettate, gli elementi del paesaggio come il fogliame sono molto compatibili con molti disegni, compreso quello del Louvre (Inv. 7126, Loisel n. 718) che è molto vicino alla Festa Campestre di Marsiglia (ora universalmente riconosciuto come di Agostino) ma che è stato identificato da Ann Sutherland Harris come un episodio della storia di Giasone e Era, indiscutibilmente realizzato nel periodo della decorazione di Palazzo Fava. La Harris ha dimostrato in maniera abbastanza enfatica che questo stile a penna e inchiostro è caratteristico di Agostino, e allora noi dobbiamo tornare agli schemi prospettici e allo staffage di figure presenti nel suo studio di Ercole per capire che qui egli mostra il suo lato pedagogico, come avrebbe potuto fare con uno dei suoi studenti dell’Accademia degli Incamminati per insegnare loro come realizzare figure a distanza e fuori scala. Benché ci possano essere delle analoghe ragioni perché li facesse anche suo fratello, è ipotizzabile che questo tipo di articolazione spaziale fosse invece intrinseca nel linguaggio di Agostino, tanto che lo ritroviamo ripetutamente in tutti i suoi paesaggi. Realmente sembra che lo studio per il Camerino fosse stato pensato in un momento in cui, come ricordato da Agucchi, i due fratelli stavano lavorando in armonia su ciò che, a qual tempo, era un progetto interamente condiviso.

Un altro disegno, associato con Bellerofonte e Chimera del Camerino (Inv. 7204, Loisel n. 473), non fu realmente utilizzato per la decorazione, ha una diversa ragione per essere di Agostino: la bestia mitologica si basa sulla Chimera scoperta negli anni ’60 del Cinquecento a Arezzo, e può considerarsi una raffinata citazione antiquariale e il paesaggio con i suoi archi che regrediscono e che portano a un castello turrito è invece di un tipo che può essere riferito alla mano del fratello.

Sembra come se fosse stato prodotto un diverso disegno per varie scene, in collaborazione con l’antiquario Fulvio Orsini, e alcune vennero o no adottate. Ma abbiamo subito l’impressione che il suo ruolo fosse quello di fornire alla narrazione una gamma di soggetti mitologici che poi avrebbero potuto dare alla mano del pittore un guizzo da purosangue, fornendo idee, spesso a penna e inchiostro, che venivano poi rifinite nella seconda fase del progetto. Potrebbero esserci stati altri contribuii di Agostino al complesso iconografico del Camerino, perché sembrerebbe che questo progetto sia stato completato effettivamente durante un periodo di interruzione dei lavori della Galleria, invece che immediatamente dopo l’arrivo di Annibale a Roma nel novembre 1595.

In tempi recenti, nella divisione del lavoro abbiamo seguito la tradizione secondo la quale Annibale aveva fatto l’intera volta: ‘le reste de la voute, entreprise enorme, est de la main d’Annibal, alors qu’Augustin semble avoir été seulement chargé de taches insignifiantes comme le dessin de divers blasons’, come scrisse Charles Dempsey nel 1988.

Siamo spinti a vedere la sua mano anche in Glauco e Scilla e in Cefalo e Aurora. Questo è il periodo della serie di dipinti Love in the Golden Age di Vienna, incisi da Agostino e considerati come rappresentativi del suo stile pittorico, mentre ora si pensa siano molto più vicini allo stile di Pauwels Franck (Paolo Fiammingo) e soltanto incisi da Agostino. La gran parte della connoisseurship del XVII secolo e dell’età moderna ha teso ad etichettare lo stile dei disegni e dei dipinti di Agostino come un lavoro di secondo livello, malgrado l’ammirazione mostrata per le due scene sui due lati del Trionfo di Bacco nella Galleria.

La maggior parte dei disegni associati in qualche maniera alla Galleria erano automaticamente attribuiti ad Annibale, e l’entusiasmo per la cultura classica, che era l’elemento distintivo della personalità di Agostino, è stato dato invece al primo. Esisteva un patto tra i due, come suggerisce l’ aneddoto raccontato da Cavedone: Agostino rimaneva un passo indietro nella reale esecuzione dell’opera. Noi però dovremmo guardare l’impatto che ebbe, nel dirigere il tutto, la sua personalità che fu sicuramente molto maggiore di quanto finora ipotizzato. Ovviamente nulla è tolto ai meravigliosi dipinti e ai magici disegni realizzati da Annibale nel corso dell’esecuzione del lavoro. Ma, certamente, con il procedere dell’opera, Annibale non aveva più veramente bisogno di disegni preparatori, e la vasta crescita apparente di produzione per esempio di disegni di paesaggio rappresentata da una produzione grafica commerciale, è abbastanza estranea a ciò che conosciamo del suo triste declino anche mentre la volta stava per essere completata. In verità, fu la preoccupazione di Agostino per una pianificazione complessiva del lavoro, che fece di lui non solo l’architetto del complesso apparato decorativo, ma anche l’inventore della formula compositiva come, per esempio, le cariatidi che dividono lo spazio in segmenti, e il progetto del paesaggio che ebbe un ruolo molto importante nelle decorazioni eseguite e Bologna. Se accettiamo il principio che Annibale era un pittore intuitivo che raramente permetteva a se stesso di essere distratto dalla prospettiva geometrica, da motivi ornamentali architettonici, non saremo lontani dalla realtà della sua geniale capacità di essere in grado di lavorare con un’eccezionale facilità all’interno di un contesto realizzato da altri. E in più dovremmo ammettere che la sfida della volta della Galleria Farnese era così complessa che richiedeva molto più dell’abilità di un pittore di talento per una rappresentazione che fosse avvincente, malgrado la spesso riconosciuta abilità per fare questo lavoro senza disegni preparatori – ‘poiché faceva di sua fantasia senza tener il naturale davanti’ -, come ci dice Mancini (op. cit., 1956, I p. 219). Ecco perché ci sono meno disegni per le figure di quanti se ne aspetterebbero per un progetto di questa importanza.

Già nel 1964 Walter Vitzhum, pubblicando a Madrid due importanti affreschi per la Galleria Farnese, capì che il gruppo di studi a penna e inchiostro, realisticamente associati alla fase preparatoria della Galleria, fosse difficilmente associabile allo stile di Annibale, dicendo che questi erano ‘much softer, not to say weaker’ (‘molto più tenui, per non dire più deboli’, ndt).

“Sono possibili dei confronti con i disegni per la Tazza Farnese, e con alcuni della fase pre-romana; alcuni disegni a penna e inchiostro, attribuiti a Annibale, lasciano spesso lo spettatore impreparato di fronte alla leggendaria qualità degli studi a carboncino della Galleria Farnese”.

In realtà, questi disegni a penna e inchiostro sono il risultato delle riflessioni e delle ricerche iconografiche di Agostino, e ciò che rimane delle prove dei suoi disegni per la struttura della volta. Senza giungere alle conclusioni che stiamo cercando di raggiungere, Vitzthum ‘found a neat stylistic separation between Annibale on the one side, and Agostino and Ludovico on the other …frequently reduced to the question as to which of the two is graphically the more vigorous’ (‘trovò una netta separazione stilistica tra Annibale da una parte, e Agostino e Ludovico dall’altra… frequentemente ridotto alla domanda di chi tra i due fosse più vigoroso dal punto di vista grafico’, ndt). In questi studi si ha l’impressione che Agostino stesse costantemente provando ad affinare i contorni, anche ripetendo profili e pose, cercando in effetti di offrire al fratello soluzioni per le figure e per le strutture architettoniche.

Ritorna quindi il patto raccontato da Cavedone sull’implicita collaborazione di Agostino: questi doveva necessariamente giocare un ruolo secondario pur essendo il reale regista di tutta l’opera.

Esiste una differenza sostanziale tra il sostenere che Agostino fosse il responsabile dell’intero apparato iconografico della Galleria Farnese, e di qualche dipinto, e che fosse semplicemente presente a Roma per un breve periodo. Questo periodo dovrebbe essere compreso tra il luglio del 1599, quando arrivò a Roma dopo aver finito un ritratto a Parma, e il 20 agosto 1599, quando Bonconte inviò al padre a Bologna la descrizione generale del superlavoro di Annibale a Palazzo Farnese. Chiaramente non conosciamo tutte le soste che Agostino fece nel suo viaggio verso Roma; ma certamente il suo ruolo deve essere stato molto diverso da quello di suo fratello, che per quanto avesse bisogno di lui, non gradiva la sua direzione, così che la presenza di Agostino potrebbe essere stata intermittente. Come uomo di corte e letterato Agostino non era legato a un numero specifico di ore di lavoro manuale, e quindi aveva la possibilità di viaggiare più frequentemente. Dovremmo ipotizzare che, malgrado fosse arrivato tardi e Roma e i suoi continui allontanamenti dalla città, l’artista fosse strettamente coinvolto nella progettazione e nell’esecuzione dei dipinti della Galleria, come per l’appunto dimostrano sia i disegni che gli affreschi e, come ricorda Agucchi quando racconta dell’armonioso rapporto di lavoro tra i fratelli, almeno all’inizio dell’opera. La maggior parte dei problemi risiedono nel fatto che da subito si è ritenuto Annibale il solo responsabile dell’intero progetto, idea che in qualche maniera fu incoraggiata e diffusa dallo stesso Annibale ma anche, indubbiamente, dall’attrazione che hanno da subito provocato i suoi fantastici affreschi. È ancora abbastanza difficile distinguere le due mani, e per quanto siamo molto vicini a capire il tratto a penna di Agostino, è altrettanto vero che fu anche abile nell’usare il carboncino nero con lumeggiature di biacca, tecnica nella quale il fratello eccelleva. È abbastanza utile considerare come Agostino disegnasse i paesaggi, i paesaggi con le figure, e anche come realizzasse gli ornamenti, le cariatidi, le maschere, i bassorilievi; non solo ricorreva a una gran quantità di pose differenti, incastri di arti associati tra di loro (scorci di gambe, braccia e visi) ma era anche in grado di far prendere loro forma di una modanatura architettonica, come se fossero stemmi.

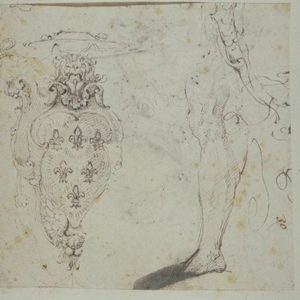

Da queste osservazioni, Ann Sutherland Harris ha recuperato il disegno di un cartiglio per un fregio, ora nelle Gallerie Nazionali della Scozia, Progetto per un Fregio con Ignudi in un paesaggio che è sufficientemente vicino ai disegni di Agostino che incise per i frontespizi tanto da non lasciare dubbi che sia lui il suo autore.

Le figure di supporto sono frequenti sulle pareti di Palazzo Fava tanto quanto sono familiari le numerose tavole incise dal catalogo di Diane de Grazia delle incisioni di Agostino. Il paesaggio è un caratteristico piccolo sketch con un arretramento a scalare di una serie figure dal più vicino cavaliere, un linguaggio composto che torna di volta in volta. Ora possiamo vedere che l’altro disegno spagnolo pubblicato da Vitzthum nel 1964, nella Biblioteca Nacional, uno Studio per due pannelli ovali e Cupidi associati è tipico delle fantasie scultoree di Agostino, come gli stemmi che vediamo nell’ Epithelia del 1600 per il matrimonio Farnese/Aldobrandini o negli Stemmi del Cardinale Facchinetti (De Grazia 1996) o per gli Stemmi di un Cardinale, De Grazia 2001); e la scrittura che definisce le dimensioni dei telai e il soggetto è della stessa mano del poema sul retro del paesaggio di Agostino al Louvre, Inv 7120 (verso).

Come notato da Vitzthum, le dimensioni contrassegnate nei medaglioni sono vicine a quelle reali nella Galleria, anche se l’annotazione del soggetto (La caduta di Fetonte) non si incontra nella volta stessa; ciò suggerisce che Agostino forniva una serie di temi che potevano essere scelti. Abbiamo già visto la predilezione di Agostino per i cupidi intorno a cornici e alcune di queste invenzioni devono essere dietro quelle che circondano gli emblemi sulle pareti della Galleria, provenienti, dopo che egli ebbe lasciato Roma, dai disegni del suo studio. Non è il principale avanzamento che dallo studio di Edimburgo, che non è legato a una particolare decorazione, porta al disegno di un gruppo di cariatidi del Louvre (Inv 7419) che Martin riteneva (n. 41) “probabilmente un’idea precoce per a Galleria Farnese “. Il gruppo paesaggistico brevemente indicato è in realtà una abbozzo che Agostino ha usato molto, con certe caratteristiche, ciascuna disegnata al minimo: dalla coppia di tronchi d’albero, alla coppia di figure disegnate a testa in giù come punti escalmativi, dal paesaggio che si allontana con cinque segmenti di linee curve che trasmettono la distanza. Martin stava pensando evidentemente a questo come precedente alla progettazione molto più evoluta della penna e inchiostro dell’Ecole des Beaux-Arts con gli schiavi michelangioleschi e gli Ercole Farnese dietro, giustamente associati alla Galleria stessa. Questo è strettamente legato alla illustrazione del Prado, (Inv. 138, (IV), pubblicata da Vitzthum nel 1964),

che ha anche cornici architettoniche e una scultura fittizia a corone che stanno in cima a una balaustra. Entrambi i disegni richiamano le sculture classiche, a Parigi con l‘Ercole Farnese in una nicchia, a Madrid con le Tre Grazie in un’altra.

Naturalmente fu Agostino che incise quel soggetto nelle sue stampe (De Grazia 183, Bartsch 130), ma lo inserì anche in un medaglione ovale nell’incisione del Fan (De Grazia 193, Bartsch 193) un’idea che ci ricorda la predilezione dell’artista per forme elaborate e volute che questi disegni presentano. Un altro studio di questo tipo è l’elaborato progetto del soffitto al Louvre (Inv. 7416), con cui condivide molti pensieri riguardo all’architettura e alle modanature, ai cartigli e anche agli stemmi che noi giustamentepensiamo come il territorio di Agostino, e agli stessi gigli che si trovano nell’indiscusso disegno di Agostino al Louvre (Inv. 7137), con il suo cartiglio con il giglio Farnese e la tipica gamba smontata. Vitzthum vide che questo indubbio disegno di Agostino per lo Stemma Farnese era quello delle pareti della Galleria, alla fine di ciascuna delle lunghe pareti, dimostrando così l’effetto duraturo dei disegni di Agostino anche nella seconda fase della decorazione. In realtà, l’elaborato lavoro a penna e inchiostro del Louvre (Inv. 7416), che anticipa da vicino il motivo di inquadramento dei riquadri finali delle storie di Polifemo (ma senza il soggetto stesso), mostra anche che Agostino era coinvolto nell’intero spartimento, perché esso arriva al livello dei capitelli e implica proposte per le nicchie con dentro i busti. Sul verso ha una veduta del Ponte Sisto che è strettamente legata al più elaborato disegno di Agostino a Chatsworth,

una vera e propria veduta dal ponte verso il Palazzetto Farnese, che è abbastanza inequivocabile nella sua elaborata calligrafia nonostante la sua altalenante storia attributiva. Il disegno, nell’Ecole des Beaux-Arts (Inv Fonds Masson, 2287)dovrebbe essere letto come una preziosa indicazione di quanto la progettazione di Agostino ha contribuito riguardo al progetto che Annibale avrebbe fatto proprio e anzi dovremmo riesaminare non solo altri studi di questo tipo, ma anche i ricordi rappresentati dai disegni “Perrier” di strutture architettoniche della collezione del Louvre. Questa divisione del lavoro coincide con la collaborazione simbiotica che la Galleria rappresenta, come avvenne in precedenza a Palazzo Magnani.

Il disegno completamente lavorato per una parte finale della volta (Louvre, Inv. 7148; Martin, n. 43, Fig.

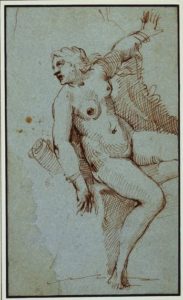

145) è caratteristico della concisione di Agostino per le figure di supporto scultoreo ed è solo minimamente attento al soggetto di figura al centro. Il progetto Windsor “per la sezione intermedia del fregio” uno studio molto animato a penna e inchiostro (Inv. 2155, Wittkower n. 287, Fig. 29) si riferisce anche al disegno a gesso nero a Stoccarda (Washington show, No. 41) che ha ugualmente un’idea non adottata per una scena Bacchica con figure approssimativamente disegnate. Ancora una volta le figure (Windsor Inv 2155) sono un tentativo molto indicativo di una scena pensata come relativa al Trionfo di Bacco (quando stava per far parte della decorazione a parete) ed è interessante che la figura femminile in posa semi adagiata (così spesso trattata da Agostino) è un’eco di una Venere di Tiziano, in gran parte una novità seguita all’arrivo dei Baccanali a Villa Aldobrandini a Montemagnanapoli.

Ma questi sono schemi abbandonati, il disegno è veramente più concentrato sul quadro, che è nuovamente oggetto dello studio di Stoccarda. Sul verso del disegno di Stoccarda vediamo una delle caratteristiche vedute frontali di Agostino di una gamba, in controparte a quella del suo disegno (Louvre Inv. 7185) che presenta uno dei suoi studi per l’affresco dell’Aurora nella Galleria da un lato e uno studio più dettagliato per il Trionfo sul recto.

Quest’ultimo sposta il soggetto da un fregio laterale al centro del soffitto e presenta alcune caratteristiche, come la ragazza con un cesto in testa, che vengono utilizzate nell’affresco di Annibale (all’estrema destra della composizione), e il centrale Satiro danzante. Il disegno di Stoccarda, insieme alla gamba sul verso, ha un cartiglio con un putto sostenitore dell’emblema Farnese delle tre iridi, che è probabilmente uno dei contributi di Agostino alle iconografie dello schema.

Un altro disegno che si trova più facilmente nel campo di Agostino è il fregio decorativo del Louvre (Inv. 7421), descritto da Martin (n. 49, fig. 45) come “uno studio iniziale per la cornice delle scene ottagonali del soffitto” che con un buona esecuzione di un bordo ad ovulo mostra il sens of humor di Agostino, con il bambino che si nasconde dietro una maschera mentre un leone (?) dalla lunga coda lo annusa. Purtroppo non abbiamo i disegni che Annibale spedì da Roma ad Agostino per una revisione, eseguiti a penna grossa ombreggiata di lapis nero, che sarebbero stati un punto di confronto, ma il tramite sembra il grande disegno di una Processione Bacchica a Vienna (Albertina, vedi sopra) che aggiorna il progetto del fregio ad un singolo episodio.

Questi disegni si riferiscono principalmente al contesto della volta, un progetto complesso la cui risoluzione segna un importante successo. Ma la collaborazione tra i due fratelli ovviamente funzionò piacevolmente in questo periodo (come ha osservato Agucchi), e il tema del Trionfo di Bacco, da un fregio tripartito (come originariamente previsto da Annibale quando inviò i suoi primi studi per farli rivedere da suo fratello a Bologna / Parma), fu posto in una scena centrale con le due scene secondarie più importanti di Cefalo e Aurora e Glauco e Scilla assegnate ad Agostino. Uno dei primi studi del Trionfo, cioè il disegno di Agostino al Louvre (Inv 7185,) è di una fase in cui doveva ancora essere un fregio ed è strettamente associato al tema dell’Aurora per via dello studio di quella figura sul verso nell’affresco di Agostino.

Per quanti ritengono che Agostino fosse assente in questa fase di lavori, tutto ciò non è conveniente, tanto da spingere Francesco Mozzetti a suggerire che il soggetto non ha nulla a che fare con Palazzo Farnese, bensì con una presunta decorazione a Bologna. Ma il ruolo di Agostino era quello di fornire suggerimenti per l’iconografia e l’impianto complessivo, per cui questi studi di penna e inchiostro sono abbozzati e spesso molto diversi da quanto Annibale scelse, come il disegno di Windsor di cui sopra (Inv 2155). È sempre sembrato difficile comprendere il rapporto di alcuni degli studi associati al Trionfo di Bacco, in particolare quelli a penna e inchiostro, con il prodotto realizzato sul soffitto, poiché alcune delle idee hanno minore rilievo. Riconoscendo che i disegni, come i due in Albertina (Inv. 2144, 2148) sono spesso proposte “disordinate” di Agostino per il soggetto si rende molto più facile la comprensione della loro collaborazione, che comprende anche disegni più grandi di tutta la scena come al Louvre (Inv 8048; Vitzthum Fig. 4). Vitzthum comprensibilmente vide questo disegno, che con il suo inserimento di un elefante come cavalcatura di Bacco, fa pensare alle ricerche archeologiche di Agostino (e forse di Fulvio Orsini), tanto “manifestamente alla stessa mano” quanto i disegni dell’ Ecole des Beaux-Arts e del Prado per la Galleria; ma è apparso spesso troppo debole per essere un originale.

Ci sono altri casi di idee di Agostino, come la figura eretta di Giunone nella scena con Giove e Giunone, o la

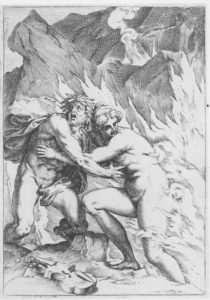

posa di Polifemo nella penna e inchiostro nel Louvre (Inv 7196) che essenzialmente hanno fornito proprio il tipo di figura che Annibale avrebbe adottato, nei suoi disegni e nell’affresco reale. Un altro satiro tracciato sullo sfondo ripete la stessa caratteristica nello studio a carboncino di Stoccarda (***). È stato spesso notato che la scelta di Polifemo come soggetto di affreschi a ciascuna estremità della Galleria echeggia quella di Pellegrino Tibaldi nella Sala d’Ulisse a Palazzo Poggi di Bologna, ed è ovvio che questi sarebbero stati accessibili ad Agostino più che allo stesso Annibale:

il disegno del Louvre è senza dubbio il contributo di Agostino al ricordo del precedente di Bologna. Questi studi hanno spesso fatto propendere per “un’idea precoce” per un tema poi sviluppatosi in modo piuttosto diverso sull’affresco, perché in realtà Annibale era sempre più intento all’improvvisazione, piuttosto che a seguire un cartone o un disegno stabilito.

diverso sull’affresco, perché in realtà Annibale era sempre più intento all’improvvisazione, piuttosto che a seguire un cartone o un disegno stabilito.

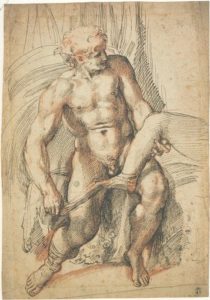

Non aveva bisogno del modello davanti a lui, era abbastanza capace di lavorare con la memoria, e l’insofferenza che aveva rispetto alle idee che dovevano essere introdotte nel soggetto a causa della pignoleria di suo fratello è palpabile. In questi cambiamenti ci immaginiamo la sua capacità di trasformazione, che produceva modelli di dinamismo veramente barocchi, e tuttavia non senza il continuo richiamo ad Agostino. Il disegno principale del gesso nel Louvre per Polifemo (Inv. 7319; Loisel No. 529) è magnifico; ma il protagonista è lavorato in modo diverso in un altro disegno di Polifemo (Inv 7197; Loisel No. 530) per il quale è stato spesso fatto il nome di Agostino in passato. È uno studio che incorpora la posa più evoluta di Annibale della figura principale, ma include anche gli elementi del paesaggio – una breve indicazione degli alberi nell’ultimo affresco – e il gruppo di Galatea.

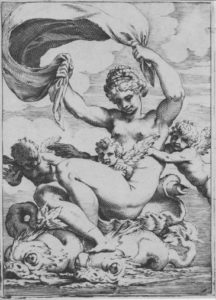

Qui lei e la sua compagna riflettono la progettazione della stampa di Agostino, (De Grazia n. 181) con i delfini che la sostengono, sollevando sopra di lei il panno di stoffa che avrebbe utilizzato anche nell’affresco del Palazzo del Giardino dello stesso tema. Nel caso di Venere e Anchise Agostino aveva preparato un disegno della singola figura di Anchise che spogliava Venere, uno studio accuratamente tracciato che non fu ignorato da Annibale quando dipinse la scena ma con un’interpretazione leggermente meno erotica. Riconosciamo la gamma di ripetuti tratti della penna, sempre seguendo la modellazione di ogni curva tridimensionale nel corpo e l’uso di tratti più sottili per trasmettere l’ombreggiatura, ma sempre con un preciso profilo lineare. È una tecnica che contrasta con la scelta preferita del chiaroscuro di Annibale che usa le morbide pressioni del carboncino, rafforzate dal bianco: abbiamo l’impressione che molti dei suoi disegni venissero successivamente tracciati a colpi di penna per passare ad una fase successiva del disegno o alla pittura finale.

L’idea delle caprette nel Trionfo di Bacco, come nello studio a penna e inchiostro a Windsor, è evidentemente della stessa mano del disegno di Agostino al Louvre (Inv. No. 7121; Loisel No. 325) o dello stesso tema a Stoccolma, sottolineando la sua struttura con il mezzo e con l’animazione degli animali. La capacità di Agostino di rivitalizzare i marmi che vide a Roma, e di rendere accessibile l’arido classicismo di un archeologo come Fulvio Orsini, trova il suo più grande successo nei due affreschi realizzati in entrambi i lati della scena centrale di Annibale sulla volta. Orsini può essere stato lo studioso che rese accessibili alcuni delle antichità che si riferiscono alle immagini, ma non fu la fonte della loro traduzione nel vivido linguaggio del classicismo barocco che ebbe un impulso così potente con questo progetto. La sensuale vitalità del gruppo centrale di Glauco e Scilla non viene da un inedito bassorilievo classico e se la ninfa a sinistra della stessa composizione deriva, come si sospetta, da una pietra preziosa incisa o da un’altra preziosa scultura, questa non è scialba imitazione. Entrambe le scene sono traduzioni ideali dell’idioma del bassorilievo in marmo classico, dallo spessore ugualmente limitato di un fregio dipinto, sequenze straordinariamente ben disposte di figure che in qualche modo hanno lo stesso volume delle figure di Caravaggio – ma qui perché la prospettiva spaziale viene deliberatamente scartata a favore di un equivalente dipinto di un sarcofago classico.

Ciò dà vita a quelle antiche lapidi, con Glauco che sta effettivamente palpeggiando il monte di Venere di Scilla, solo che nello stesso affresco ha il pudore di coprire con un drappo il suo godimento nell’abbraccio. C’è una preoccupazione quasi manierista nel riempire tutta la superficie, con drappeggi raffinati e con le code dei tritoni che riempiono le lacune verticali e i cupidi volanti che in qualche modo non vengono resi plumbei. Molti dei disegni di Agostino si occupano ripetutamente di arrivare alla soluzione di corpi in altorilievo, come se fossero l’equivalente dei sostenitori di stemmi o cariatidi a sostegno di una trabeazione, un compito molto diverso dai soggetti paesaggistici che egli ha anche provato ad elaborare, con una precisa calibrazione della distanza. I cartoni della National Gallery e i disegni associati a questi temi mostrano quanto sia difficile tracciare una linea tra l’opera dei fratelli, e rendono possibile che altri studi per cariatidi e figure sul soffitto non debbano essere automaticamente registrati come del fratello minore, il quale è giustamente associato ad alcuni degli studi più delicati a carboncino con lumeggiatura bianca e potrebbe essere stato responsabile delle correzioni agli stessi affreschi di Agostino, in quello spirito di collaborazione fraterna che aveva segnato l’attività commerciale della famiglia.

Fu una sfida enorme al primato del ruolo di Annibale nel dipingere le parti più importanti della Galleria per Agostino, che infine avrebbe dovuto competere con suo fratello nelle parti centrali e questo andò contro l’intesa che avevano tra di loro. Naturalmente una delle glorie della  Galleria è indubbiamente la ricchezza della struttura, i diversi strati della realtà che richiamano, e siamo costantemente sorpresi dal contrasto tra i colori vivi degli affreschi, la tridimensionalità delle cariatidi e l’illusionismo dei motivi architettonici e delle inquadrature. Se Agostino ebbe a giocare la sua parte nell’inventare una parte di questa quadratura, si trattò un supremo tour de force che sembra molto più convincente delle ricette per la prospettiva standard offerta da personalità come Cavalier d’Arpino o Baldassare Croce e la geometria di Zaccolini e Guidubaldo Del Monte. Agostino cercò di dare un effetto notturno nel lato del suo affresco dell’Aurora, ma questo blu scuro venne scambiato per una successiva aggiunta in uno dei restauri del soffitto del ventesimo secolo. I medaglioni in bronzo fittizio sono altrettanto impressionanti, e può essere che Agostino abbia giocato una parte qui, nella scelta del motivo, ma anche nell’esecuzione di queste caratteristiche.

Galleria è indubbiamente la ricchezza della struttura, i diversi strati della realtà che richiamano, e siamo costantemente sorpresi dal contrasto tra i colori vivi degli affreschi, la tridimensionalità delle cariatidi e l’illusionismo dei motivi architettonici e delle inquadrature. Se Agostino ebbe a giocare la sua parte nell’inventare una parte di questa quadratura, si trattò un supremo tour de force che sembra molto più convincente delle ricette per la prospettiva standard offerta da personalità come Cavalier d’Arpino o Baldassare Croce e la geometria di Zaccolini e Guidubaldo Del Monte. Agostino cercò di dare un effetto notturno nel lato del suo affresco dell’Aurora, ma questo blu scuro venne scambiato per una successiva aggiunta in uno dei restauri del soffitto del ventesimo secolo. I medaglioni in bronzo fittizio sono altrettanto impressionanti, e può essere che Agostino abbia giocato una parte qui, nella scelta del motivo, ma anche nell’esecuzione di queste caratteristiche.

La scena con Cupido che schiaccia Pan è un tema che aveva realizzato a Bologna (in Palazzo Magnani) e avrebbe ripetuto nella stampa Omnia Vincit Amor e sembrerebbe molto probabile che anche questo affresco sia opera delle sue mani. Allo stesso modo il medaglione con Orfeo e Euridice ha molti paralleli con la stampa che Agostino fece, probabilmente nello stesso periodo, com pure le figure di Leandro ed Ero hanno

paralleli nel paesaggio di Palazzo Pitti che gli è affidabilmente riconosciuto, e il Ratto di Europa è la composizione che ha dipinto nel piccolo paesaggio già in collezione Farnese. In sostanza, sembra che le principali scene della Galleria, incluse le scene finali con Polifemo, dovessero essere stati completati oppure ancora in corso quando Agostino lasciò Roma nell’estate del 1600. L’origine dell’interesse per la natura erotica e sensuale dei soggetti, la prurience di questa visione privata degli amori degli Dei, deve essere vista alla luce del contrasto con la persecuzione di Clemente VIII verso l’industria del sesso. Si può ben argomentare che la censura che il papa rivolse verso Agostino, e che è segnalata da Malvasia, deve aver riguardato le pubblicazioni che circolavano a Roma. Sicuramente l’inizio delle invenzioni originali di Agostino delle cosiddette Lascivie risale al periodo degli affreschi Farnese, e la censura di Clemente VIII data a questo periodo, piuttosto che prima a Parma, Bologna o Venezia, come parte della ricerca pratica che Agostino faceva sull’industria del sesso per la sua comprensione degli amori degli Dei.

E sebbene la scala delle figure nei due principali temi trattati da Agostino in Galleria sia necessariamente diversa, quelle di queste stampe coincidono con quelle dei dipinti più piccoli da cavalletto che ora conosciamo, da Roma e poi da Parma. Susanna, nella Susanna e i Vecchioni, richiama la posa di Andromeda nel piccolo quadro di Parma, e l’invenzione del panno di stoffa che Galatea tiene sopra la sua testa è quello che porta nell’affresco dove guarda Polifemo.

È sostenuta dai delfini nel Glauco e Scilla di Agostino e da quelli del suo Peleo e Teti / Galatea a Parma. La posa di Andromeda (chiamata anche Hesion) riecheggia quella di Europa nel piccolo dipinto già in collezione Farnese e negli studi ripetuti per Galatea, come nel disegno su entrambi i lati di Agostino nel Metropolitan o in uno all’Albertina di Vienna. Ma la scala di queste figure compatte classiche è quella dei dipinti narrativi ora attribuiti ad Agostino, come quelli del paesaggio con Diana e Callisto a Mertoun. La combinazione con il naturalismo che suo fratello riuscì a raggiungere, una magica struttura con forma umana, insieme all’immaturità di un patrono che non sembra mai accettare completamente la carriera religiosa cui il destino lo aveva chiamato, è la spiegazione più salda dello straordinario tenore dei temi rappresentati nel soffitto. Da Bellori, c’è sempre stata la necessità di cercare un programma per questa serie di scene, ma questo è come chiedere un libretto prima di un’opera, e dobbiamo essere contenti di riconoscere in esse ciò che Mancini ha descritto come profondissimo sapere di Agostino. Agostino evidentemente aveva molte idee per rendere visivamente intelligibili le storie mitologiche, e sembra, come vedremo, che alcune di queste idee sopravvivano alla sua partenza dalla scena romana del trionfo di suo fratello. C’era evidentemente un continuo utilizzo delle idee di Agostino anche sulle lunghe mura della Galleria, e abbiamo la sensazione che ci fossero delle tematiche alternative che avrebbero potuto essere usate, una delle quali è la Caduta di Fetonte citata nel medaglione in un disegno della Biblioteca Nazionale (***) .

Alcuni dei disegni della volta, come la composizione oblunga per Pan e Diana a Chatsworth (JR Martin, No. 72), mostrano che il suo uso come uno dei soggetti verticali indica che ci fossero molte scelte, e anzi, l’applicazione di tutti i vari formati significa che dovevano essercene persino alcuni di riserva. Lo scudo con gli stemmi Farnese, realizzato da Agostino nel disegno del Louvre (Inv 7137), venne utilizzato alla fine delle pareti, che apparentemente riprende il disegno progettato in alcuni degli studi precedenti di Agostino (come Inv 7146 e le copie “Perrier” ). L’idea di Agostino sullo stemma dell’Accademia degli Incamminati di Carracci, l’orso disegnato a Windsor Inv. 2002 (Wittkower No. 158), viene utilizzato nella parte dipinta della trasformazione di Callisto che si riferisce alla composizione di Agostino del dipinto ex Farnese di Diana e Atteone ora a Bruxelles. Ed in confronto con le più tarde pale d’altare, opera interamente dello studio fedele, c’è almeno una certa continuità nello stile delle scene dipinte sulle pareti. Il complesso contrappunto che esiste tra i soggetti delle due scene alle due estremità della Galleria, del Perseo e di Fineo e di Perseo e Andromeda, è di una sottigliezza che può provenire solo dall’erudizione di Agostino. Come J. Beldon Scott ha notato questo mito si basa sul paragone tra scultura e pittura, con l’eroina che appariva in un dipinto come una pietra, e fu solo la brezza nei capelli di Andromeda e le lacrime agli occhi che mostrarono a Perseo che lei non era una statua, mentre dall’altro lato è una la cui trasformazione in una statua di marmo avviene solo per metà, mentre l’altra metà, con Fineo nella posa del torso del Belvedere e Perseo in quella dell’Apollo del Belvedere. Dato che lo sfondo culturale della Galleria Farnese era l’apprezzamento moderno della scultura classica come accadeva ormai ovunque intorno, questo esercizio intellettuale era proprio in sintonia con quello dei cortigiani a cui Agostino esponeva. Ma è anche interessante che l’Andromeda, dipinta in parte da Domenichino che venne a Roma dopo l’abbandono di Agostino, evidentemente si riferisce ancora al disegno di Agostino come lo conosciamo dalle due stampe che di solito sono incluse nella serie delle Lascivie e il modello usato è strettamente simile alla donna che ha disegnato con Anchise nel dipinto che Annibale fece di Anchise e Venere a sinistra dell’incisione di Agostino di Glauco e Scilla. Riconosciamo lo stesso modello nella stampa di Orfeo ed Euridice di Agostino, in cui si collocano sullo stesso focolaio del vulcano. Queste sono composizioni in verticale, e il problema che Annibale aveva, e con lui la sua bottega, era adattarlo alle proporzioni paesaggistiche monumentali dell’estremità orientale della Galleria. Tuttavia questi personaggi, nelle stampe di Agostino erano il frutto della sua esperienza classica, ed era lui che comunicava con Fulvio Orsini e l’Accademia dei Gelati di Bologna, a cui apparteneva. Il suo disegno di Andromeda al Louvre, rivela la stessa mano e lo stesso modello dello studio di Anchise di Christchurch (Inv 7303, Loisel 553) e sembra essere stato utilizzato per l’affresco sulla parete est della Galleria, qualche tempo dopo che Agostino aveva lasciato Roma.

Sia il disegno del Louvre, che quello di Windsor (Martin, No. 140, Wittkower, Disegni Carracci, Cat. 301, Inv. 2003) hanno il caratteristico tratto di Agostino. Sebbene di solito attribuiti ad Annibale perché evidentemente si riferiscono all’affresco, sono anche legati alla stampa di Agostino (De Grazia 179), e infatti il mostro che la minaccia dal profondo è evidentemente dalla stessa famiglia di quelle delle stampe (De Grazia 179, 180). La roccia su cui è incatenata Andromeda (Gibilterra) si ritrova nell’affresco come nel

focolaio vulcanico piuttosto simile allo sfondo della stampa di Orfeo ed Euridice di Agostino (De Grazia 178).

focolaio vulcanico piuttosto simile allo sfondo della stampa di Orfeo ed Euridice di Agostino (De Grazia 178).

La volta della Galleria ha presentato una sfida diversa rispetto ai soffitti piatti di Palazzo Fava e Palazzo Magnani. Se i disegni di penna e inchiostro per il Trionfo di Bacco sono realmente di Agostino, egli allora ha partecipato alla decisione finale di dedicare il centro della volta a questo tema piuttosto che farlo come fregio sulle pareti.

Sembra che scaturisca da questa scelta di progettazione che toccò a lui essere autore delle scene adiacenti di Cefalo e Aurora, e Glauco e Scilla. Le due scene di Polifemo in entrambe le estremità della Galleria, con l’eco di Tibaldi a Palazzo Poggi, possono forse essere considerate come un’idea che viene da Agostino, così come il contrappunto di Fineo e Andromeda sotto di loro, e possiamo discernere la sua mente dietro l’invenzione anche attraverso la predominanza della mano del fratello nell’esecuzione dell’intero progetto. È ancora un punto cruciale stabilire quanta parte ebbe in tutto ciò Innocenzo Tacconi: egli arriva a Roma probabilmente all’inizio del lavoro, nel 1598, guadagnando sempre più la fiducia di Annibale, in particolare con le commissioni esterne, fino alla Venere dormiente ora a Chantilly, un lavoro particolarmente rivelatore, quasi nonostante la lunga descrizione di Agucchi, pubblicata da Malvasia.

di Clovis WHITFIELD

English text . Agostino in the Farnese Gallery. New point of view. Part 2

There are many instances of drawings that have strayed into Annibale’s attributed authorship, and only a complete review of the graphic work will make it possible to recover the separate identities of the numerous participants in the Carracci studio. But these drawings in pen and ink may well be the key to understanding the role Agostino played, because several of them are devoted to architectural elements, and seem leave the scenes that they surround blank or with only a hint of a generic composition. By contrast the real studies by Annibale are concerned with individual figures, with an incredible mastery of chiaroscuro interpreted in charcoal with white highlights, and rarely have a defined margin. It suggests that this was the role agreed between the two brothers that is implied in Cavedone’s account, and that while Annibale was definitely the star painter, he needed his brother to define the spartimento of the vault, needed to have him provide the framework of the whole. Following the praise that he received for the caryatids in Palazzo Fava, we can see that Agostino used all his ingenuity to arrive at an incredible variety of poses for the supporting figures that are such a major part of the Farnese ceiling. In these there are references to antiquities in the Farnese collection, and it may well be that it is he who is responsible for this iconographic research that has usually been thought of as a characteristic of his brother. The sources actually give us the impression that Annibale had little urgency to study in this way: it was Agostino who was the first to visit Rome (in about 1581) when his brother stayed in Bologna. This is perfectly in line with the wide-ranging stylistic familiarity that he had had, encountering many artists from other schools and engraving their works, an experience that led directly to the recognition of what later would be called the eclecticism of the Carracci. Although his famous poem celebrating Niccolò dell’ Abate has been much ridiculed for the idea of a ‘mix and match’ culture that was long associated with the Carracci, to their detriment, we would do well to remember how Agostino’s curiosity for other cultures and styles was a hallmark of the Carracci reform, something that took it far beyond the usual family workshop tradition. The surviving drawings do not give a complete picture of the brothers’ symbiotic relationship, but they do illustrate rather well the way in which the collaboration worked, for the eventual design often shows the independent creativity of Annibale’s actual brushwork, which needed guidance and containment but not so much preparation on his part. The kind of stylistic analysis undertaken by scholars like Ann Sutherland Harris and Diane de Grazia has been vital in sorting out some of the characteristics of their styles, from the confusion that evidently existed almost from the outset.

Quite often if they do have a theme that relates to the actual paintings, these drawings that may be by Agostino are referred to as ‘a first idea’ to account for the fact that a different pose come into play in other studies, and are only indirectly related to the finished product in the Galleria. It is obviously not sufficient to underline Agostino’s preference for pen and ink, because there are also drawings in charcoal that is his brother’s medium of choice, and many examples where his use of wash is quite liberal. Gradually a few however have been recovered, like the majority of the studies for the Tazza Farnese, and the graphic style of the elder brother has been much better defined, particularly through the efforts of Ann Sutherland Harris. An important group, around the late engraving of St Jerome, gives a clear idea of his repeated attempts to arrive at a suitable invention, and this re-iteration is also evident in the drawings for the Palazzo del Giardino frescoes, notably those for the figure of Galatea. This is not the place to attempt to review the full range of studies that have been possibly mis-attributed, but to look at a few where it is more obvious. The sheet of studies in the Louvre (Inv 7210, Loisel No. 470) with a study for the Death of Hercules, on one of the lintels in the Camerino, and perhaps because it is quite close to the fresco itself, has long been considered to be a study by Annibale, and of additional interest because of the landscape study that accompanies it, and the perspective diagrams. But this handling of the anatomy is foreign to Annibale, and other features like the grasshoppers, the faceted rock and the landscape elements and foliage are very comparable with the drawing, also in the Louvre (Inv 7126, Loisel No. 718) which is close to the Marseille painting of the Fête Champeêtre (now universally recognised as Agostino’s) but which has been identified by A.S. Harris as representing an episode in the story of Jason and Hera, undoubtedly done at the time of the Palazzo Fava decorations. Harris has demonstrated quite emphatically that this pen and ink style is characteristic of Agostino, and we then turn to the perspective diagrams and staffage figures of the Hercules study to realise that this is the pedagogical side of his nature to show, as he might have done, one of the students from the Incamminati how to work out the scale of distance for background figures. Although there might equally be a reason for his brother to do this, it is arguable that this kind of articulation is really intrinsic to Agostino’s work, and is to be found in his landscapes repeatedly. It does look as though the study for the Camerino fresco is from a moment when, as Agucchi describes, the two brothers were working harmoniously, on what was then entirely a joint project. Another drawing associated with the Camerino, Inv. 7204 (Loisel 473) of a lunette whose subject, Bellopheron and the Chimera, was not actually used in the decoration, has a different claim to be Agostino’s; the mythical beast is based on the Chimera that had been discovered in the 1560s in Arezzo, a characteristically antiquarian refinement, and the landscape with its successive receding arcs leading to a turreted castello is of a type that is typical of the elder brother’s hand. It looks as though he was producing alternative designs for the various scenes, in collaboration with the antiquarian Fulvio Orsini, and sometimes they were, or were not adopted. But we get the impression already of the his role of providing the narratives of a range of mythologies that then could be given full-blooded expression at the hand of the painter, providing ideas, often in pen-and-ink, that were then worked up in the next stage of the design. There may well be other contributions by Agostino to the iconography of the Camerino, for it does seem that this project was actually completed during a period of interruption of work on the Galleria rather than immediately after Annibale’s arrival in Rome in November 1595.

In the division of labour we have, in modern times, followed Annibale’s claim to have done the whole of the vault ‘le reste de la voute, entreprise enorme, est de la main d’Annibal, alors qu’Augustin semble avoir été seulement chargé de taches insignifiantes comme le dessin de divers blasons’, as Charles Dempsey wrote in 1988, and even in the two panels of Glaucus and Scylla and Cephalus and Aurora we are encouraged to find the younger brother’s hand. This was still a time when the series of paintings of Love in the Golden Age in Vienna, that Agostino had engraved, were still thought of as representative of his painting style, whereas they are now regarded as being much closer to that of Pauwels Franck (Paolo Fiammingo) and only engraved by Agostino. Much of seventeenth century and modern connoisseurship has tended to recognise Agostino’s style in drawings and paintings as second tier work, despite the admiration for the two panels either side of the Triumph of Bacchus in the Galleria. Most of the drawings connected in any way with the Galleria were attributed automatically to the brother, and the enthusiasm for classical learning that was the hallmark of Agostino’s personality was given instead to the former. If there was a pact between them, as Cavedone’s anecdote suggests, then Agostino did take a back seat in the actual execution, and we should instead look for the impact of his personality in the direction of the whole, which may be far more extensive than has been imagined so far. Nothing will detract from the astonishing paintings, and the magical drawings that Annibale produced in the course of the execution of the designs; but increasingly he did not need to do preparatory drawings, and the vast apparent increase in production represented by the traded graphic production, for example of landscape drawings – is quite foreign to what we know of his sad decline even while the ceiling was being completed. In reality it was Agostino’s concern with overall planning that made him not only the architect of the design of the whole, but also the inventor of the compositional formulae of elements like the caryatids dividing each segment, and the framework of landscapes that had such an important role in Bolognese decoration. If we adopt the principle that Annibale was an intuitive painter who rarely allowed himself to be distracted by the design of geometrical perspective, architectural motifs and ornament, we will not be far away from the reality of his gift of being able to work with tremendous ease within the framework provided by others. And we would have to acknowledge that the challenge of the design as the Farnese ceiling was so complex that it demanded much more than the abilities of one who had such a talent for representation that was compelling despite the often acknowledged ability to do this work without preparatory designs ‘poiché faceva di sua fantasia senza tener il naturale davanti’ as Mancini tells us (op. cit, 1956, I p. 219) . So there are fewer drawings for individual figures in the frescoes than would be expected from a project of this scale.

Already in 1964 the late Walter Vitzhum, publishing two important drawings for the Farnese Gallery in Madrid, realised that the group of pen and ink studies realistically associated with the design stage of the Farnese Gallery, are difficult to reconcile with Annibale’s style, seeing them as ‘much softer, not to say weaker’. ‘Parallels are possible with the drawings for the Tazza Farnese, and with the few pre-Roman pen and ink drawings which have been suggested as Annibale’s, where the beholder is frequently left unprepared for the heroic quality of the chalk studies of the Farnese Gallery’. In reality these pen and ink drawings represent the results of Agostino’s musings and iconographic research, and what remains of the evidence of his designs for the framework of the vault. Without coming to the conclusion we can now reach, Vitzthum ‘found a neat stylistic separation between Annibale on the one side, and Agostino and Ludovico on the other …frequently reduced to the question as to which of the two is graphically the more vigorous’. In these studies there is an impression that Agostino was trying constantly to refine his outlines, ever repeating profiles and poses, in effect attempting to offer design solutions – and frames – to his brother. In the event Annibale’s response takes in the gist of the problem, and often made a quite different choice of forms that come from his intuition and needed only comparatively minor adjustment from his own first idea. It is like the pact that is implied in Cavedone’s account of Agostino’s collaboration, necessarily playing second fiddle but at the same time being the actual conductor.

There is a very different interpretation between the idea that Agostino was responsible for the whole iconography of the Farnese Galleria and some of the execution, and that he was only present in Rome for a very brief period as has been the most recent direction of the analysis of the events, that he only arrived in Rome after finishing a portrait in Parma in July 1599, and was already absent when Bonconte sent his description of Annibale’s overworking in Palazzo Farnese to his father in Bologna on August 20 1599. Clearly we do not have all Agostino’s travel arrangements, and his role must have been very different from that of his brother who clearly needed but did not welcome direction, so his presence may well have been intermittent. As a courtier and a letterato he was not tied to the hours of a manual worker, and probably travelled more frequently. We should assume, despite his late arrival and periodic absence, that he was closely involved with the design and execution of the Galleria, as indeed the drawings and paintings show, a narrative coinciding with Agucchi’s account of their harmonious start on it together. Much of the problem lies in the early belief that Annibale was solely responsible for the whole project, something that the artist himself promoted, and the undoubtedly attraction of his almost magical touch. It is still very difficult to distinguish the separate hands, and although we are closer to understanding Agostino’s penmanship, he was also quite able to use black charcoal with white highlighting, which was his brother’s most impressive medium. It is quite useful to take account of Agostino’s use of drawing for landscape, of landscape detail in conjunction with figures, and also to recognise that he was closely involved with ornament, caryatids and masks, figures almost in bas relief in a huge variety of poses, the dovetailing of limbs associated together, the foreshortening not only of legs, arms and facial features but their moulding into architectural forms like coats of arms.

From such observations Ann Sutherland Harris has recovered the drawing of a cartouche for a frieze, now in the National Galleries of Scotland, Design for a Frieze with Ignudi framing a Landscape which is sufficiently close to Agostino’s designs for frontispieces he engraved to leave no doubt that he is its author. The supporting figures are frequent flyers on the walls of Palazzo Fava as well as the many engraved bookplates familiar from Diane de Grazia’s catalogue of Agostino’s engravings. The landscape is a characteristic slight sketch with a scaled recession of staffage figures from the nearer horseman, a composed idiom that he returned to time and again. We can see now that the other Spanish drawing Vitzthum published in 1964, in the Biblioteca Nacional, a Study with two oval Panels and Associated Cupids is typical of Agostino’s sculptural fantasies, like the coats of arms we see in the 1600 Epithelia for the Farnese / Aldobrandini wedding, or the Arms of Cardinal Facchinetti (De Grazia 196) or a Bishop’s Arms (De Grazia 201); and the handwriting setting out the dimensions of the frames and the subject is the same hand as the poem on the back of Agostino’s landscape in the Louvre, Inv 7120 (verso). As Vitzthum noted, the dimensions marked in the medallions are close to those of the actual ones in the Galleria, although the annotation of subject (the Fall of Phaeton) is not encountered in the vault itself, this suggests that Agostino provided a range of subjects that could be chosen from. We have already seen Agostino’s predilection for cupids around frames, and some of these inventions must be behind those that surround the emblems on the walls of the Galleria, sourced after he had left Rome from among the drawings in the studio. It is not a major step from this study in Edinburgh, which is not linked to a particular decoration, to the drawing in the Louvre of a caryatid group (Inv 7419) that Martin thought (No. 41) thought ‘probably an early idea for the Farnese Gallery’. The briefly indicated landscape panel is actually a shorthand that Agostino used a lot, each feature minimally drawn, from the pair of tree trunks, the pair of figures drawn like upside down exclamation marks, the receding landscape with five segments of curved lines that convey distance. Martin was evidently thinking of this as preceding the much more evolved design of the Ecole des Beaux-Arts pen and ink drawing with the bound Michelangiolesque slaves and the Farnese Hercules behind, rightly associated with the Galleria itself. This is closely linked to the drawing in the Prado, (Inv. 138, (IV), published by Vitzthum in 1964), which also has architectural frames and a wreath-bearing fictive sculpture sitting atop a balustrade. Both drawings have recollections of classical sculptures, in Paris it is the Farnese Hercules in a niche, in Madrid the Three Graces in another. It was of course Agostino who had engraved that subject in his print (De Grazia 183, Bartsch 130), but he also included it in an oval medallion in the engraving of the Fan (De Grazia 193, Bartsch 193) a design that reminds us of the artist’s predilection for elaborate frames and volutes that these drawings feature. Another such study is the elaborate project of the ceiling in the Louvre (Inv. 7416), with which it shares a lot of thoughts for the architecture and mouldings, cartouches and even coats of arms that we rightly think of as Agostino’s territory, the same fleur-de-lys that are in the undisputed Agostino drawing Louvre Inv. 7137, with its cartouche of the Farnese fleur de lys and a typical disembodied leg. Vitzthum saw that this undoubted Agostino drawing for the Farnese arms are those of the walls of the Galleria, at the end of each of the long walls, demonstrating the enduring effect of Agostino’s designs even in the second stage of the decoration. In reality the elaborate pen and ink drawing in the Louvre (Inv. 7416), which anticipates closely the framing motif of the end panels of the stories of Polyphemus (but without the subject itself) also shows that Agostino was involved with the whole spartimento, for it reaches down to the level of the capitals and involves suggestions for the niches with busts between. On the verso it has a View of the Ponte Sisto that is closely linked to Agostino’s more elaborate drawing at Chatsworth, a real view from downstream of the bridge looking towards the Palazzetto Farnese, which is quite unequivocally in his elaborate penmanship despite its checkered attributional history. The drawing, in the Ecole des Beaux-Arts (Inv Fonds Masson, 2287) should be read as a precious indication of what Agostino’s designing contributed to the project that Annibale would make his own, and indeed we should re-examine not only the other studies of this kind, but also the recollections represented by the ‘Perrier’ drawings of architectural frameworks in the Louvre collection. Such a division of work coincides with the symbiotic collaboration that the Gallery represents, much as Palazzo Magnani was before. The fully worked design for an end section of the vault (Louvre, Inv. 7148; Martin, No. 43, Fig 145) is characteristic of Agostino’s shorthand for his sculptural supporting figures, and is only minimally concerned with the figure subject in the middle. The Windsor ‘Design for the middle section of the frieze’ a very lively study in pen and ink (Inv. 2155, Wittkower No. 287, Fig. 29) also relates to the black chalk drawing in Stuttgart, (Washington show, No. 41) which equally has an unadopted suggestion for a Bacchic scene with figures roughly sketched in. Again the figures (Windsor Inv 2155) are a very tentative indication of a scene that has been thought of as relating to the Triumph of Bacchus (when it was going to be part of the wall decoration), and it interesting that the semi reclining female form (so often worked over by Agostino) is an echo of a Titian Venus, much in the news since the arrival of the Bacchanals at Villa Aldobrandini a Montemagnanapoli. But these are throw-away outlines, the drawing is really more concentrated on the framework, which is again the subject of the Stuttgart study. On the verso of the Stuttgart drawing we see one of Agostino’s characteristic front views of a leg, the counterpart to that of his drawing (Louvre Inv. 7185) which has one of his studies for the Aurora fresco in the Galleria on the other side and a more detailed study for the Triumph on the recto . The latter moves the subject from a lateral frieze to the centre of the ceiling, and has some features, like the girl with a basket on her head, that are used in Annibale’s fresco (on the far right of the composition), and the central dancing satyr. The Stuttgart drawing, along with the leg on the verso , has a cartouche with a putto supporter of the Farnese emblem of the three irises which is most likely one of Agostino’s contributions to the emblematics of the scheme. Another drawing that falls more readily into Agostino’s camp is the decorative frieze in the Louvre Inv. 7421, described by Martin (No. 49, Fig. 45) as ‘an early study for the frame of the octagonal panels of the ceiling’ which with a good rendering of an egg-and-dart border has Agostino’s sense of humour, with a child sheltering behind a mask as the long tailed lion (?) sniffs at him. Unfortunately we do not have the drawings that Annibale sent from Rome for Agostino to review, they were done in penna grossa ombreggiata di lapis nero that would have been a point of comparison, but the medium sounds like the large drawing of a Bacchic Procession in Vienna (Albertina, see above) that already revises the frieze project to a single episode.

These drawings are in the main concerned with the framework of the vault, a complex design whose resolution is a major triumph. But the collaboration between the two brothers obviously worked sweetly at this period (as Agucchi observed), and moved the idea of the Triumph of Bacchus from a tripartite frieze (as originally envisaged by Annibale when he sent his first studies for review by his brother in Bologna/Parma) to a central scene with the two most important secondary scenes of Cephalus and Aurora and Glaucus and Scylla allocated to Agostino. One of the first studies of the Triumph, Agostino’s drawing in the Louvre (Inv 7185) is at a stage where it was still to be a frieze, and is closely associated with the Aurora subject because of the study for that figure in Agostino’s fresco on the verso. It is inconvenient for those who find Agostino to be absent at this stage, prompting Francesco Mozzetti recently to suggest that the subject has nothing to do with Palazzo Farnese, but a putative decoration in Bologna. But the role of Agostino was to provide suggestions for iconography and overall design, which is why these pen and ink studies are so sketchy and are often quite different from what Annibale eventually chose, like the Windsor drawing referred to above (Inv 2155). It has always seemed difficult to comprehend the relationship of some of the studies associated with the Triumph of Bacchus, particularly those in pen and ink, with the finished product on the ceiling, for some of the ideas have very little relevance. Realising that drawings like the two in the Albertina (Inv. 2144, 2148) are Agostino’s often ‘messy’ suggestions for the subject makes understanding their collaboration a lot easier, as it also makes encompassing larger drawings of the whole scene such as Louvre Inv 8048 (Vitzthum Fig 4). Vitzthum understandably saw this drawing, which with its inclusion of an elephant as Bacchus’s mount suggests Agostino’s (and perhaps Fulvio Orsini’s) archaeological researches, as ‘manifestly by the same hand’ as the Ecole des Beaux-Arts and Prado drawings for the Galleria; but it has often seemed too weak to be an original.

There are other instances of Agostino’s providing ideas, like the standing figure of Juno in the scene with Jupiter and Juno , or the pose of Polyphemus in the pen and ink drawing in the Louvre (Inv 7196) essentially giving just the kind of figure Annibale would adopt, in his drawings and in the actual fresco. Another shorthand satyr in the background repeats the same feature in the Stuttgart charcoal study about ( ***). It has often been noticed that the choice of Polyphemus as the subject of frescoes at each end of the Galleria echoes that of Pellegrino Tibaldi in the Sala d’Ulisse in Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, and it is obvious that these would have been accessible to Agostino more recently than Annibale himself: the Louvre drawing is doubtless Agostino’s contribution to this recollection of the precedent in Bologna. Such studies have often prompted the reaction ‘an early idea’ for a design that worked out quite differently on the fresco, because in reality Annibale was all the time more intent on improvisation rather than following a cartoon or an established design. He had no need of the model in front of him, was quite capable of working from memory, and the impatience that he had with the ideas that were to be introduced into the subject because of his brother’s pedantry is palpable. In this exchange we seem his transformative ability, producing a model of really baroque dynamism, but not without a continuing repartee from Agostino. The main chalk drawing in the Louvre for Polyphemus (Inv. 7319; Loisel No. 529) is magnificent; but the protagonist is worked differently in another drawing of Polyphemus(Inv 7197; Loisel No. 530) for which the name of Agostino has often been mentioned in the past. It is a study that incorporated Annibale’s more evolved pose of the main figure, but also includes the elements of the landscape – a brief indication of the trees in the final fresco – and the group of Galatea. Here she and her companion reflect the design of Agostino’s print, (De Grazia No. 181) where the dolphins support her, raising above her the billowing cloth that the latter would also use in the Palazzo del Giardino fresco of the same subject. In the case of Venus and Anchises Agostino had prepared a drawing of the single figure of Anchises undressing Venus, a carefully cross-hatched study that was not ignored by Annibale when he painted the scene but with a slightly less titillating interpretation. We recognise the range of repeated strokes of the pen, always following the modelling of each three-dimensional curve in the body, and using closer strokes to convey shading, but always with a precise linear outline. It is a technique that contrasts with Annibale’s preferred choice of chiaroscuro using the soft impressions of charcoal, heightened with white: we do have the impression that many of his drawings had subsequently to be outlined with pen strokes for the design to be transferred, to the next stage or the final painting. The idea of the bucking goats in the Triumph of Bacchus, seen in the pen and ink study at Windsor , is evidently from the same hand as Agostino’s drawing in the Louvre (Inv. No. 7121; Loisel No. 325) or the same theme in Stockholm, emphasising his facility with the medium and with animal animation.

Agostino’s capacity for revitalising the marbles that he saw in Rome, and for making the dry classicism of an archaeologist like Fulvio Orsini seem accessible, finds its greatest achievement in the two frescoes he did either side of Annibale’s central panel on the vault. Orsini may have been the scholar who accessed some of the antiques that are referred to in the images, but he was not the source of their translation into the vivid language of baroque classicism that had such a powerful impulse in this project. The sensuous vitality of the central group of ? Glaucus and Scylla does not come unedited from a classical bas-relief, and if the nymph on the left of the same composition derives, as one suspects, from a engraved gemstone or other precious carving, this is no tame imitation. Both panels are ideal translations of the idiom of the classical marble bas-relief to the equally limited depth of a painted frieze, extraordinarily well-disposed sequences of figures that somehow have the same volume of Caravaggio’s figures – but here because spatial perspective is deliberately eschewed in favour of a painted equivalent of a classical sarcophagus. This gives life to those old stones, with Glaucus actually fingering the bare mons Veneris of Scylla – only in the fresco itself does she have the modesty of a drapery to cover her enjoyment of the embrace. There is an almost mannerist concern with filling the entire surface, with flamboyant drapery and tritons’ tails filling vertical gaps, and flying cupids who are somehow not leaden. Many of Agostino’s drawings are concerned with repeatedly trying to arrive at the solution of bodies in high relief, as if they are the equivalent of supporters of coats of arms or caryatids holding an entablature, a quite different task from the landscape subjects that he also tried to elaborate, with a precise calibration of distance. The cartoons now in the National Gallery, and the drawings that are associated with these subjects, show how difficult it is to draw a line between the work of the brothers, and make it likely that other studies for caryatids and figures on the ceiling need not be automatically registered as by the younger brother, who is rightly associated with some of the most sensitive studies in charcoal with white highlighting, and may have been responsible for corrections to Agostino’s frescoes themselves., in that spirit of fraternal collaboration that had marked their family business. It was a tremendous challenge to the primacy of Annibale’s role in painting the most prominent parts of the Galleria that Agostino should at last rival his brother in these central pieces, and it must have run counter to the understanding that they had between them.

Of course one of the glories of the Galleria is indeed the richness of the framework, and the various layers of reality that they echo, and we are constantly marvelling at the contrast between the lifelike colours of the frescoes, the three-dimensionality of the caryatids and the illusionism of the architectural and framing motifs. If Agostino played his part in inventing some of this quadratura, it was a supreme tour de force that seems much more compelling than the recipes for standard perspective offered by people like Cavalier d’Arpino or Baldassare Croce, and the geometry of Zaccolini and Guidubaldo Del Monte. Agostino tried to give a night effect on the side of his Aurora fresco, but this dark blue was apparently mistaken for a later addition in one of the twentieth century restorations of the ceiling. The medallions in fictive bronze are equally striking, and it may be that Agostino played a part here, in the choice of the motif but also perhaps in the execution of these features. The scene with Cupid overpowering Pan is a subject that he had done in Bologna (in Palazzo Magnani) and would repeat in the print Omnia Vincit Amor and it would seem most likely that this fresco is again from his hand. Equally the medallion with Orpheus and Eurydice has many parallels in the print that Agostino did, probably at the same period, and the figures in Hero and Leander have parallels in the landscape at Palazzo Pitti that is reliably given to him, and the Rape of Europa is the composition that he painted in the little landscape formerly in the Farnese collection. Altogether it must seem as though the main scenes of the Galleria, including the end panels with Polyphemus, must have been complete or in progress when Agostino left Rome in the summer of 1600.

The origin of the interest in the sexual and sensual nature of the subjects, the prurience of this private view of the loves of the Gods, has to be seen in the light of the contrast with Clement VIII’s persecution of the sex industry. It can well be argued that the censure that the Pope directed at Agostino, and which is reported by Malvasia must have been at publications that were circulating in Rome. Surely the time of Agostino’s original inventions of the so-called Lascivie is from the period of the Farnese frescoes, and Clement’s reputed censure of them dates from this period, rather than in distant Parma, Bologna or Venice, part of the practical research that Agostino did into the sex industry in his understanding of the loves of the Gods.. And although the scale of the figures in the two main subjects Agostino painted in the Galleria is necessarily different, those of these prints do coincide with that of the smaller easel paintings that we now know, from Rome and later in Parma. Susanna, in the Susannah and the Elders, looks forward to the pose of Andromeda in the little panel in Parma, and the invention of the billowing cloth that Galatea holds above her head is what she supports in the fresco where she eyeballs Polyphemus. She is supported by the dolphins of Agostino’s Glaucus and Scylla, and those of his Peleus and Thetis / Galatea in Parma. The pose of Andromeda (also called Hesion) is an echo of that of Europa in the little painting formerly in the Farnese collection, and of the repeated studies for Galatea as in Agostino’s double-sided drawing in the Metropolitan Museum, or the one in Vienna, Albertina But the scale of these compact classical figures is that of the narrative paintings now attributed to Agostino, like those of the Landscape with Diana and Callisto at Mertoun. The combination with the naturalism that his brother was able to achieve, a magical facility with human form, together with the immaturity of a patron who never seems to have fully accepted the religious career that fate had landed him with, is the soundest explanation of the extraordinary tenor of the themes represented in the ceiling. Since Bellori, there has always been a need to look for a programme for this series of scenes, but this is to ask for a libretto before we have an opera, and we should be content to recognise in them what Mancini described as Agostino’s profondissimo sapere. Agostino evidently had a lot of ideas to make mythological stories visually intelligible, and it does seem, as we shall see, that some of these ideas did survive his departure from the Roman scene of his brother’s triumph.