di John T. SPIKE

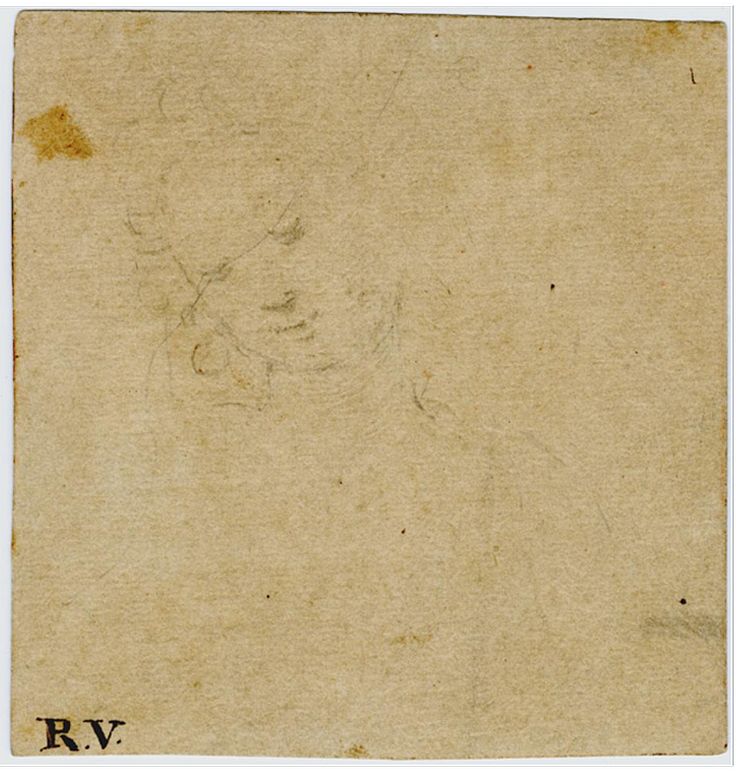

One of the curiosities of twentieth- and twenty-first century art historical scholarship is the enthusiasm with witch attributions are announced as ‘discoveries’, when, for the most part, they are, in truth, ‘recoveries’ of earlier attributions that had been forgotten or fallen out of use – sometimes as recently as a mere one hundred years ago. A interesting case in point came to mind this week with regard to a small drawing of a girl’s face in the British Museum 1946,0713.499 (Fig. 1). Too small and too faint to see very well, this modest work has eluded a convincing attribution and therefore the attention of scholars for the past sixty years. Fortunately, back in 1962, Philip Pouncey and John Gere, two of the greatest connoisseurs of Italian drawings in modern times, looked at it very carefully indeed. This is what they wrote in their authoritative catalogue of ‘Italian Drawings in the British Museum: Raphael and His Circle’ (no. 61, pl 64). First they described the image as exactly as possible: ‘ “The figure seems to be wearing some sort of diadem- or turban-shaped headdress with what may be a short veil hanging down beside the face’. Then, they explained the collector’s mark, added in pen and ink: R.V. : ‘The Antaldi mark makes it necessary to take this timid little drawing – so slight as to be almost invisible – more seriously than its apparent merits deserve.’ And, finally, without wishing to exaggerate, they summed up their connoisseurs’ response to this ‘timid little drawing’, “It is impossible to say more of it than that it is probably Umbrian and of the early sixteenth century, and seems to be Raphaelesque”. The Viti-Antaldi collection of Umbria was the most important corpus of drawings by the young Raphael, which were preserved by his friend and compatriot,, the painter Timoteo Viti. These drawings have long been the proud possessions of important museums. While not all of the R.V. drawings are attributed today to Raphael, most of them are.This week, while reading the Raphael pages on the website of the British Museum, as I do often, this small drawing of a girl’s head reminded me of a drawing in the Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia. The drawing, which is one of four such elegant heads found on a single page, once universally attributed to Raphael, but for the past century abandoned in favor of an anonymous follower of Perugino. It is thoroughly documented by Sylvia Ferino Pagden in her superb catalogue (1984) of the ‘Disegni umbri’ in the Accademia (Fig. 2). Thanks to Sylvia’s research — whom I address by her first name, since we were both students of Konrad Oberhuber and thus friends for more than forty years –, I learned at once that the drawing in Venice is based on a figure in Perugino’s fresco, Circoncisione e il viaggio di Mosè, in the Sistine Chapel (Fig. 3). It would usually be hard to find a specific face in a huge Perugino fresco, but, as if to help me out, my friend also included this photograph. On the facing page in this wonderful ‘Disegni umbri’ (p. 168), appears an x-ray of a young man’s face (Fig. 4), which appears on a similar page in the Libretto veneziano, as one can see (Fig. 5). The comparison serves to demonstrate that the British Museum drawing is so slight because it is similarly an underdrawing in black chalk for a more elaborate drawing in pen and ink. While the old attributions of these three four drawings to Raphael are not maintained today, perhaps someday they will be ‘recovered’.

Una delle curiosità relativa agli studi storico artistici del XX e XXI secolo è l’entusiasmo per le attribuzioni che vengono annunciate come “scoperte”, quando, per la maggior parte, sono, in verità, “recuperi” di precedenti attribuzioni che erano state dimenticate o cadute in disuso – a volte fino a cento anni fa.

Questa settimana mi è capitato un caso interessante riguardante un piccolo disegno del volto di una ragazza che si trova nel British Museum dal 1946 (0713,499) (Fig. 1).

Troppo piccolo e troppo debole per vederlo molto bene, questo piccolo lavoro ha eluso un’attribuzione convincente e quindi l’attenzione degli studiosi negli ultimi sessant’anni. Fortunatamente, nel 1962, Philip Pouncey e John Gere, due dei massimi intenditori di disegni italiani nei tempi moderni, lo osservarono con molta attenzione. Questo è ciò che hanno scritto nel loro autorevole catalogo di “Disegni italiani nel British Museum: Raphael and His Circle” (n. 61, pl 64), partendo dalla descrizione delle immagini nel modo più preciso possibile:

“La figura sembra indossare una sorta di copricapo a forma di diadema o turbante con quello che potrebbe essere un velo corto che pende accanto al viso”.

Quindi, hanno tradotto il marchio del collezionista, R.V., aggiunto a penna e inchiostro:

“Il marchio Antaldi rende necessario prendere questo timido piccolo disegno – così lieve da essere quasi invisibile – più seriamente di quanto apparentemente non sembri meritare.”

E, infine, senza voler esagerare, hanno riassunto il loro responso di veri intenditori circa il ‘timido disegno’

“È impossibile dire di più di questo, cioè che probabilmente è umbro dei primi del XVI secolo, e sembra essere Raffaellesco”.

La collezione umbra di Viti-Antaldi Lugt 2246 fu il corpus più importante di disegni del giovane Raffaello, che furono conservati dal suo amico e connazionale, il pittore Timoteo Viti. Questi disegni sono stati a lungo motivo di orgoglio tra i possedimenti di importanti musei. E se è vero che non tutti quelli con il marchio R.V. siano disegni attribuiti oggi a Raffaello, tuttavia molti di loro lo sono.

Questa settimana, mentre leggevo le pagine dedicate a Raffaello sul sito web del British Museum, come faccio spesso, questo piccolo disegno del volto di una ragazza mi ha ricordato un disegno nelle Gallerie dell’Accademia di Venezia. Il disegno, che raffigura una delle quattro teste così eleganti ritrovate su una sola pagina, fu una volta universalmente attribuito a Raffaello, ma dal secolo scorso abbandonato a favore di un anonimo seguace del Perugino.

Esso è ampiamente documentato da Sylvia Ferino Pagden nel suo superbo catalogo (1984) dei “Disegni umbri” nell’Accademia (Fig. 2). Grazie alla ricerca di Sylvia – a cui mi rivolgo per nome, dato che eravamo entrambi studenti di Konrad Oberhuber e quindi amici da più di quarant’anni -, ho subito arguito che il disegno oggi a Venezia si basa su una figura presente nell’affresco del Perugino raffigurante la Circoncisione e il viaggio di Mosè, nella Cappella Sistina (Fig. 3).

Di solito non è agvole individuare un volto specifico in un enorme affresco del Perugino, ma, come per darmi una mano, anche il mio amico ha incluso questa fotografia. Nella pagina a fianco di questo meraviglioso testo ‘Disegni umbri’ (p. 168), appare una radiografia del volto di un giovane (Fig. 4),

che compare su una pagina simile nel Libretto veneziano, come si può vedere (Fig 5).

Il confronto serve a dimostrare che il disegno del British Museum è così leggero perché allo stesso modo è un sottofondo in gesso nero per un disegno più elaborato realizzato a penna e inchiostro. E seppure le passate attribuzioni di questi tre disegni a Raffaello non vengono oggi mantenute, forse un giorno saranno “recuperate”

John T. SPIKE New York July 5 2020