redazione

La “Commedia dell’Arte” Le maschere e il Carnevale nell’arte italiana del XX secolo

Curata da Marco Fabio Apolloni e Monica Cardarelli

Laocoon Gallery, 2a-4 Ryder Street, London SW1Y 6QB; 26 November 2020 – 15 January 2021

Quando non indossa una maschera che le copre la bocca per indicare che è muta, la personificazione della pittura, come ritratta dagli antichi pittori, è una donna che mostra nella maggior parte dei casi una maschera a pieno volto appesa al collo. È il simbolo dell’imitazione della natura: l’arte imita la realtà come un attore mascherato per recitare una parte. Vogliamo ricordare questa connessione tra la maschera e la pittura con questa mostra alla Laocoont Gallery dal titolo “La Commedia dell’Arte”, che celebra le maschere italiane nell’arte del Novecento.

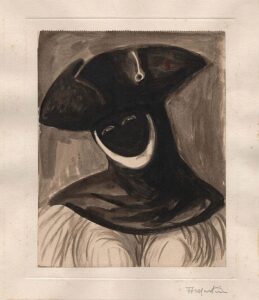

Al centro di questa raccolta tematica c’è un’opera particolare del visionario artista italiano Alberto Martini (1876-1954), precursore del surrealismo.

La sua serie del 1904 “Il Libro delle Ombre” è composta da 29 disegni a pennello e inchiostro nero di china che ritraggono volti mascherati in tutte le possibili varianti di travestimento. Volti falsi, mezze maschere, maschere per gli occhi e mantelli neri con cappelli veneziani settecenteschi a tre punte, tutti disegnati con pennellate veloci come nella pittura cinese, di carattere notturno e misterioso, illustrazioni di qualche poema drammatico e gotico le cui parole sono perdute.

Questi volti enigmatici e ossessivi sembrano le toppe di Roschach che appaiono in un incubo, popolando una notte perpetua veneziana, in cui non ci stupiremmo di incontrare gli occhi inquietanti e truccati della Marchesa Casati, famosa per i suoi eccentrici balli veneziani in maschera, per la quale Martini è stato costumista e ritrattista di corte.

Con in mente i ricordi figurativi di Tiepolo, è Venezia la capitale ideale delle maschere, con il suo antico carnevale dove sul palco dei teatri gli attori indossavano maschere così come le persone in platea.

Un grande dipinto di Ugo Rossi (1906-1990) lungo quasi quattro metri ritrae piazza San Marco a Venezia affollata di persone in coloratissimi costumi di carnevale di ogni tipo. Era tradizione appendere alla trave di una delle lussuose navi transatlantiche che erano i monumenti dell’ottimismo entusiastico del dopoguerra, un modo per rappresentare l’Italia come un paese in perenne godimento dopo gli orrori e le distruzioni del conflitto passato.

Le scene veneziane con maschere di carnevale erano uno dei temi preferiti dell’artista Umberto Brunelleschi (1879-1949), un toscano che ebbe una carriera di successo a Parigi come costumista, scenografo e illustratore alla moda.

Di lui due dei suoi tipici pochoir con corteggiamento di coppie amorose, lo studio per un manifesto dedicato a una festa veneziana svoltasi al Cercle de l’Union Interalliées di Parigi. In un altro acquerello ha tracciato un suo ritratto ed è lo studio per un manifesto pubblicitario della commedia teatrale “La maschera e il volto”, opera ormai dimenticata di Luigi Chiarelli che ebbe all’epoca ampio successo internazionale, sulla scia dell’influente esempio di Pirandello.

Direttamente ispirato da Pirandello è stato il pittore Giovanni Marchig, il cui capolavoro, “Morte d’autore” (1924), un drammaturgo morto sulla sua scrivania circondato da tutti i disperati personaggi della “Commedia dell’arte”, è ora a Palazzo Pitti. È un antico pittore, poco conosciuto perché ha rinunciato alla pittura nell’ultima parte della sua vita per diventare un famoso restauratore di vecchi maestri, molto vicino a Bernard Berenson. La sua fama attuale sta ora giungendo principalmente per essere stato l’ex proprietario del controverso disegno di Leonardo “La Bella Principessa”. La Laocoon Gallery è orgogliosa di presentare un ritratto recentemente riscoperto di Marchig (1933), di un giovane attore vestito da Arlecchino. Ha il suo costume multicolore ma non indossa una maschera, è fuori dal palco, a riposo, con le braccia conserte. L’enfasi questa volta è posta sul viso, sulla persona reale dell’attore quando non è posseduto dal suo personaggio.

Cézanne ha introdotto le maschere italiane nella pittura moderna e Picasso nel suo periodo blu ha seguito il suo esempio, ma il pittore moderno che più di tutti ha scelto e amato Arlecchino e Pulcinella come soggetti preferiti e specchi della propria anima è certamente Gino Severini (1883- 1966). Gli affreschi con danze e spettacoli in maschera che dipinse per Sir George Sitwell nel suo castello a Montegufoni in Toscana sono una gioiosa piccola cappella sistina dell’arte del XX secolo. Un grande fumetto di Severini per un “Concerto” dipinto ad olio sarà esposto insieme a due affascinanti “pochoirs” e un disegno a pastello a cera di Arlecchino e Pulcinella, propedeutico ad una celebre litografia.

Dopo la prima guerra mondiale, l’uomo che più promosse come l’apice della moda i Bals Masqués in stile veneziano del XVIII secolo fu certamente il pittore francese Jean Gabriel Domergue (1889-1962) Il suo Bal Venitien parigino all’Opera del 1922 fu solo il primo di una serie tenutasi successivamente a Monte Carlo, Cannes, Biarritz e Deauville. Disegnava i costumi, i programmi, i manifesti e ritraeva le bellezze più importanti e aristocratiche come provocanti dame veneziane in uscita dalle alcove di Casanova. Ha anche decorato residenze e locali notturni pubblici con tele dorate meravigliosamente disegnate con scene sognanti ed eleganti del carnevale veneziano. Simili a questi, ora per lo più dispersi se non distrutti, possono essere visti assemblati nella villa di Domergue a Cannes, ora un museo dove si trova la giuria del Festival del Cinema quando vengono decise le premiazioni della Palma d’Oro. Tre rari pannelli a foglie d’oro di Domergue con gondola, maschere amorose e bellissime veneziane sono i lotti visibilmente più preziosi di questa mostra. È qui al culmine della sua arte elegante.

E’ il mondo di Casanova, reinterpretato con lo spirito delle “anneés folles”. Il famoso donnaiolo veneziano è ritratto in piena maschera con un burattino mascherato in ogni mano.

È lo studio per la copertina di un’opera teatrale, “Le nozze di Casanova” (1910), in cui l’eroe protagonista del film funge da burattinaio di tutti i personaggi della trama. È opera di Oscar Ghiglia (1876-1945), il pittore prediletto di Ugo Ojetti – il più grande critico d’arte italiano dell’epoca -.

Maschere metafisiche come pezzi centrali di enigmatiche nature morte sono nei dipinti dell’allieva di Casorati Marisa Mori, altre sono in un’opera molto antica e interessante di Aligi Sassu (1929).

Tra le altre, anche una commovente illustrazione di Arlecchino portato in paradiso dagli angeli, opera dell’illustratore Enrico Sacchetti appartenuta al celebre comico Ettore Petrolini. A Sacchetti è attribuito anche il disegno originale per la copertina di una raccolta di racconti di Pirandello “Terzetti” del 1912, dove una Musa si diverte a indossare una maschera diversa dall’altra. Un altro Arlecchino è dell’artista contemporaneo Pino Pascali, risalente all’epoca in cui produceva film d’animazione per la pubblicità televisiva: Arlecchino era una marca molto rinomata di pomodori in scatola.

English Text

The “Commedia dell’Arte” Masks and Carnival in Italian 20th Century Art

Curated by Marco Fabio Apolloni e Monica Cardarelli

When: 26 November 2020 – 15 January 2021

Where: Laocoon Gallery, 2a-4 Ryder Street, London SW1Y 6QB

When she is not wearing a facemask covering her mouth to indicate is mute, the personification of painting, as portrayed by ancient painters, is a woman displaying in most cases a full face mask hanging from her neck. It is a symbol of the imitation of nature: art imitates reality, like an actor disguised to play a part. We want to remind this connection between the mask and painting for this exhibition in the Laocoon Gallery celebrating, with the title of “The Commedia dell’Arte”, Italian masks in XXth Century art.

At the centre of this thematic collection is a particular work of the visionary Italian artist Alberto Martini (1876-1954), a precursor of surrealism. His 1904 series “Il Libro delle Ombre” (The Book of Shadows) consists of 29 drawings in brush and black china ink portraying masked faces in all possible variation of disguise. Full false faces, vizards, half masks, eye masks, and black domino cloaks with venetian 18th century three cornered hats, all drawn with speedy brushstrokes as in chinese painting, nocturnal and mysterious in character, illustrations of some dramatic and gothic poem whose words are lost. These enigmatic and obsessive faces, look like Roschach’s patches appearing in a nightmare, populating some Venetian perpetual night, in which we wouldn’t be surprised to meet the heavily made up disquieting eyes of Marchesa Casati, famous for her eccentric venetian masked balls, for which Martini acted as costume designer and court portrait-painter.

With the figurative memories of the Tiepolos in mind, it is Venice, with her ancient old carnival where in theatres actors on the stage wore masks as well as the people in the audience, the ideal capital of masks.

A large painting by Ugo Rossi (1906-1990) almost four meter long portrays Venice’s piazza San Marco crowded with people in colourful carnival costumes of all kinds. It used to hang in the bar one of the luxurious transatlantic ships that were the monuments of post war enthusiastic optimism, a way to represent Italy as a country of perpetual enjoyment after the horrors and destructions of the past conflict.

Venetian scenes with carnival masks were a favourite theme of the artist Umberto Brunelleschi (1879-1949), a Tuscan who had a successful career in Paris as costume designer, scenographer and fashionable illustrator. By him two of his typical pochoirs with amorous couples courting, the study for a poster dedicated to a Venetian feast held in the Cercle de l’Union Interalliées in Paris. In another watercolour he drew his own portrait, it is the study for a poster advertising the theatre play “The Mask and the Face”, a now forgotten work by Luigi Chiarelli that had at the time wide international success, on the wake of Pirandello’s influential example.

Directly inspired by Pirandello was the painter Giovanni Marchig, who’s masterpiece, “Death of an author”(1924), a playwright dead at his desk surrounded by all the characters of the “commedia dell’arte” in despair is now in Palazzo Pitti. He’s anchanting painter, little known because he gave up painting in the last part of his life to become a famed old master’s restorer, very close to Bernard Berenson. His current fame is now mainly coming for having been the former owner of Leonardo’s controversial drawing “La Bella Principessa”. The Laocoon Gallery is proud to present a newly rediscovered portrait by Marchig (1933), of a young actor dressed up as Harlequin. He has his multi-coloured costume but he doesn’t wear a mask, he’s off stage, resting, his arms folded. The emphasis this time is on the face, on the real person of the actor when is not possessed by his role character.

Cezanne introduced Italian masks into modern painting, and Picasso in his blue period, followed his lead, but the modern painter who most of all chose and cherished Harlequins and Pulcinellas as a favorite subjects and mirrors of his own soul is certainly Gino Severini (1883-1966). The frescoes with dancing and playing masquerades that he painted for Sir George sitwell in his castle at Montegufoni in Tuscany is a joyous little Sixtine Chapel of XXth century’s art. A large cartoon by Severini for a “Concert” oil painting of … will be exhibited along with two charming “pochoirs” and a wax pastel drawing of Harlequin and Pulcinella, preparatory for a famous lithograph.

After the First World War the man who most promoted as the pinnacle of fashion 18th century’s Venitian style’s Bals Masqués, was certainly the French painter Jean Gabriel Domergue (1889-1962). His Parisian Bal Venitien at the Opera in 1922 was only the first of a series held subsequently in Monte carlo, Cannes, Biarritz and Deauville. He would design the costumes, the programmes, the posters and portray the most prominent and aristocratic beauties as provoking Venetian Ladies coming out from some of Casanova’s alcoves. He also decorated residences and public nightspots with gilded canvases wonderfully sketched over with dreamy elegant scenes of Venetian carnival. The like of these, now mostly dispersed if not destroyed, can be seen assembled in Domergue’s own villa in Cannes, now a Museum where the Jury of the Cinema Festival sits when the Palme d’or awards are decided. Three rare panels gilded with golden leaves by Domergue with gondola, amorous masks and beautiful veneziane are the most visibly precious lots in this exhibition. He is here at the height of his elegant art.

It is the world of Casanova, reinterpreted with the spirit of the “anneés folles”. The famous Venetian womanizer is portrayed in full mask with a masked puppet in each hand. It is the study for the cover of a play, “The Marriage of Casanova” (1910), in which the title role hero acts as puppeteer of all the characters in the plot. It is the work of Oscar Ghiglia (1876-1945), who was Ugo Ojetti’s – Italy’s master art critic of the time – favourite painter.

Methaphisical masks as centre pieces of enigmatical still lifes are in the paintings of Casorati’s pupil Marisa Mori, others are in a very early and interesting work by Aligi Sassu (1929). Among other a moving illustration of Harlequin taken to Heaven by angels, a work of the illustrator Enrico Sacchetti that belonged to the famous comic performer Ettore Petrolini. Attributed to Sacchetti is also the original drawing for the cover of one Pirandello’s short stories collection “Terzetti” of 1912, where a Muse amuses herself wearing one different mask after another. Another Harlequin is by contemporary artist Pino Pascali, dating at the time when he was producing animated films for television advertisement: Arlecchino used to be a very renowned brand of tinned tomatoes.

Roma 14 novembre 2020