di John T. SPIKE

-

Prologue: Salvator Rosa’s lost painting, Il Sasso

Midway through the seventeenth century, when most Roman painters were competing to depict the angels of celestial majesty, Salvator Rosa was insistently exploring the darkest depths of Nature. Despite their differences, most artists active in Rome considered themselves the descendants of classical culture. Salvator Rosa, not to be outdone, pored through Greek and Roman ancient history and mythology in search of subjects never painted before. It is the measure of Rosa’s genius that he was able to transform arcane texts and primordial cliffs and rocks into compelling compositions. The purpose of the present article is to demonstrate on the basis of new research the authenticity and artistic significance of a painting by Rosa, Soldiers in a Grotto (or briefly, Grotto).[1]

When Salvator Rosa returned to Rome in February 1649 after almost nine years at the Medici court in Florence, [2] he confided to his friends that he intended to establish himself as a philosopher-painter whose inventiveness would amaze his peers and patrons. He was soon able to report that

“Since Rome has learned how extremely extravagant my innovations are, I must now persist as much as possible.”[3]

Two years later in a letter of 27 March 1653 to his friend, the poet Giovan Battista Ricciardi, Rosa lamented the criticisms that had been heaped on him after an exhibition of one of his paintings at the Pantheon in Rome.[4] Rosa took his revenge against his detractors by sending a scandalously unconventional painting to the exhibition at the Pantheon on the feast day of San Giuseppe, 19 March 1653. He described this retaliation in a few lines in his Invidia [Envy] satire, which he was writing at this time. He stated that the subject of the painting was simply a “sasso [enormous rock], nothing else”, whose boldness would leave his critics “cracking their teeth with jealousy”, at his defiance of academic decorum.[5] Unfortunately, we know little else about this fascinating Sasso, whose subsequent whereabouts are unknown to modern scholars. New research has discovered, however, that the painting was cited twice in Naples in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. See Appendix II infra.

It was not until 1991 that Luigi Salerno revived the study of the Sasso with a proposal to identify Rosa’s lost picture with a landscape that had recently passed through an auction at Christie’s, London.[6] As evidence for his theory Salerno noted that

“The true protagonist of the composition is a large stone boulder near which two small hermits seem to have been added only to give a minimum of acceptability to the subject”.[7]

Ultimately, however, there were few differences between the London painting and other similar mountain scenes by Rosa. In 1995, Jonathan Scott politely demurred to Salerno’s proposal and offered his own hypothesis about the lost Sasso:

“The picture, which cannot now be identified, must have been a landscape which included a romantic crag, one of those beautiful and popular paintings which his critics would have found hard to fault.”[8]

Further investigation into the Sasso has been scarce since the 1990s with the partial exception of Alexandra Carol Hoare, who demonstrated Rosa’s frequent use of the word “sasso” in his poetry.[9] Dr. Hoare held out hope for the lost painting’s recovery someday.

- Salvator Rosa and the Rocky Coast of Naples [Salvator Rosa e la rocciosa costiera napoletana

Rock formations, grottoes and mountains were a lifelong fascination for Salvator Rosa on the outskirts of Naples in full view of an active volcano, Vesuvius, and only a stone’s throw away from the rocky coasts reputedly haunted by wicked sirens. Seventy years after Rosa’s death, his Neapolitan biographer, Bernardo De Dominici, cited a local legend that Rosa and another young painter, Marzio Masturzo, had developed their skills by taking to the sea in a small boat in order to

“draw the views of the beautiful coast of Posillipo as well as the coasts towards Pozzuoli. They drew almost as many coasts as had been produced by Nature”.[10]

Those awesome coasts had been shaped over millions of years by the dissolution of the soft limestone bedrock by flowing waters mingled with carbonic acid leached from the soil. The fissures were gradually widened to form caves and eventually corroded into fantastic shapes. A pair of small coastal scenes in the Palazzo Corsini in Rome are early evidence of Rosa’s lifelong penchant for compositions in which the foreground figures are overshadowed by the massive rock faces that seem to glower down at them.[11] [Fig. 2 e Fig. 3]

As in nearly all of his coastal paintings throughout his career, the rocky cliffs are pierced by the dark entrance to a grotto.[12]

Since time immemorable, certain grottoes along the Neapolitan coasts from Pozzuoli to Salerno had been venerated as the legendary abodes of sibyls, sirens and other sea monsters known from Greek and Roman mythology.[13] In his Naturalis Historia of AD 77, Pliny the Elder mentions many grottoes, including the Grotta del Cane in the Campi Flegrei, the Cave of Cumae in the volcanic hills near Pozzuoli and thus near Vesuvius, as well as the Blue Grotto in Capri. Virgil describes in the Aeneid (Book VI.64) how Aeneas, upon arriving in Cumae went immediately to find the prophetess in her “cave of wondrous size, the sibyl’s dread retreat” in order to obtain her guidance on the descent into Hades. She warned him

“Easy is the descent to Avernus, night and day the dark door of Hades stands open, but to retrace thy step and return to the upper airs, this is the task, this is the toil”.[14]

Centuries later, Dante was inspired by Virgil to adapt the Greco-Roman Underworld into Christian theology. At the dawn of the Renaissance, Leonardo da Vinci confessed his fascination with grottos:

“And after having remained at the entry some time, two contrary emotions arose in me, fear and desire — fear of the threatening dark grotto, and desire to see whether there were any marvelous thing within it.”

At the peak of the Renaissance, Michelangelo enthroned the Cumaean Sibyl as a prophetess reading from books on the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel. In his late Roman years, Rosa painted a large landscape of the god Apollo with the Cumaean Sibyl (Wallace Collection, London).

By the 1640s, when Rosa was in Florence, The Descent of Virgil and Dante into Hell had become a popular subject in art in which the two Poets were depicted at the entrance of the Grotto della Sibilla (Cumae) [Fig. 4].[15]

Travelers and explorers could find their way to the grottoes near Naples with a remarkably accurate geographical atlas by Leandro Alberti, Descrittione di tutta Italia, first published in 1568, with many reprintings. By the end of the eighteenth century, the grottoes of the Neapolitan and Salerno coasts were attracting naturalists, spelunkers and more than a few landscape painters influenced by Salvator Rosa. Among the latter, perhaps the most eminent was Joseph Wright of Derby, a British artist who came to Italy in 1774 and made several good paintings of grottoes with bandits in open homage to Salvator Rosa (Fig. 5).[16]

As De Dominici astutely noted, the creation of the awesome cliffs and grottoes so favored by Rosa were recognized by everyone to be works of art made by Nature. The philosophical belief in an eternal competition between Art and Nature has ancient roots in Pliny the Elder and Ovid (Metamorphoses); ‘Natural Magic”, magia naturalis, was a respected branch of natural philosophy, similar to disreputable necromance but distinguished by its enlightened methods of inquiry. The Florentine humanist par excellence, Pico della Mirandola ventured to say,

“There is no latent force in heaven or earth which the magician cannot release by proper inducements.”

Pico’s philosophy empowered artists in ways that aroused the suspicions of the Roman Church, for example:

“What the human magician produces through art, nature produces naturally by producing man.”[17]

In short, by inserting magical art into Nature, man can release forces that are greater than his own. Edgar Wind pointed out that Leonardo da Vinci kept this magic philosophy alive in his notebooks in the sixteenth century: “Nature is full of latent causes which have never been released” (“la natura è piena d’infinite ragioni che non furono mai in esperienza.”)[18] Closer to Rosa’s time and place was the universally known Magiae Naturalis, Naples, 1558, by the Neapolitan philosopher, Giovan Battista Della Porta (1535–1615). [19] This brief survey of the philosophical antecedents is offered as an introduction to the possible interpretations of the zoomorphic rock formations in Rosa’s Grotto.[20]

-

The Re-examination of the Recently Discovered Grotto by Salvator Rosa

In May of 2023, a large painting, 94 x 78 cm, representing a dark underground grotto passed through the art market in Florence (Fig. 1).[21] This appearance at a public auction was only the third time that the Soldiers in a Grotto by Salvator Rosa had been put on view since its rediscovery by Nicola Spinosa in a private collection in Naples in 2008. The first of the two previous opportunities to study the Grotto was its inclusion in a major exhibition, Salvator Rosa tra mito e magia, curated by Spinosa for the Capodimonte museum.[22]

The catalogue entry by Brigitte Daprà, a specialist in Neapolitan paintings, was convincing analysis of this intriguing addition to Rosa’s oeuvre, prominently signed with the artist’s ‘SR’ monogram. Some disagreements to the attribution were registered as often happens with old master paintings, although less often when they are signed.[23] Daprà’s observations on the Grotto were translated into German for the catalogue of “Caravaggios Erben – Barock in Neapel, 2016-2017, an important anthological exposition on the theme of Caravaggio and his Neapolitan followers.[24] The attribution to Rosa seems not to have been questioned at the exhibition in Germany.

The Grotto stands out in Rosa’s oeuvre as a rare example of a cavernous interior seen from the floor of the cave, looking upwards towards the entrance and a small patch of blue sky.[25] It is worth noting that Rosa employed similar points of view in his paintings of natural arches in which the small figures in the foreground seem dwarfed by the colossal rocks overhead.[26] Another particularity of the Grotto is the artist’s boldness in enveloping the interior in an opaque darkness, which optically flattens the three small figures, depriving them of the modelling effect of daylight, and rendering them almost invisible. With breathtaking originality, Rosa combined these techniques to make the awesome scene seem realistic.

The recent exhibition of the Grotto in Florence provided an occasion to re-examine the painting with an intention to review the attributions and the disagreements. On May 23rd, 2023, Rosa’s Soldiers in a Grotto, as it was entitled, was sold at an auction of old master paintings at Pandolfini Casa d’Aste in Florence.[27] The entry in the sales catalogue was researched and written by Ludovica Trezzani, an expert on Italian seventeenth century paintings, who supported the attribution and cited Brigitte Daprà’s suggestion of a possible connection between this Grotto and the lost Sasso:

“It is certainly no coincidence that in 1653 Salvator Rosa chose a rock landscape to challenge the academic world by exhibiting a painting entitled Il Sasso in Rome: an opportunity to demonstrate his technical superiority, as well as his contempt for the stable hierarchy between pictorial genres beginning with the subject.”[28]

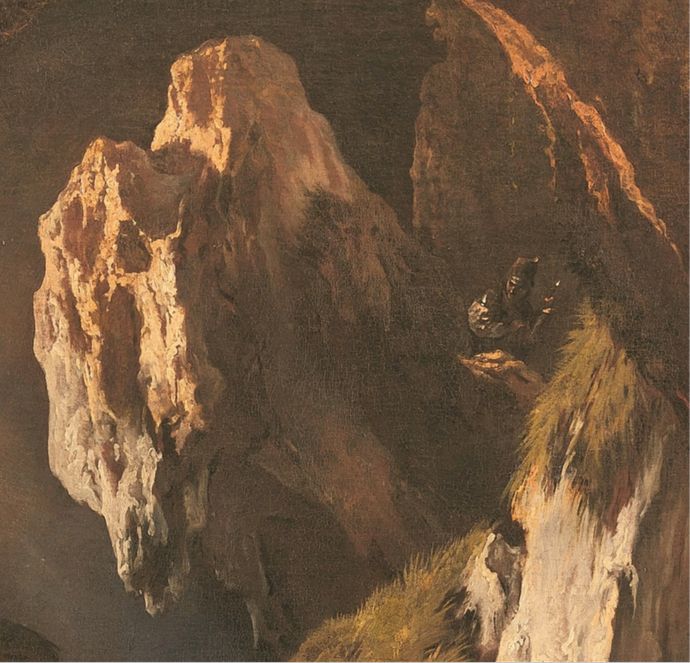

Intrigued by this rare opportunity to study Rosa’s Grotto in person, I telephoned Ludovica Trezzani and requested an appointment to view the painting together – always a useful exercise – at the preview exhibition in Florence. On Saturday morning, the 20th May, I met with Dr. Trezzani in front of the painting, which, fortunately, was brightly lit by daylight. In our exchange of views, we found that we both agreed with the attribution to Rosa as a work datable after his final return to Rome from Florence.[29] We also shared our interpretations of the core of the composition, which comprises two monstrous masses of limestone that emerge like phantoms from the pitch-black depths of the grotto. It seemed surprising that no one had previously noticed that the largest of these terrifying peaks resembles a giant wolf lunging downward towards the cavern floor where two shadowy men have taken shelter inside a carved-out boulder [Ital. massiccio]. Brigitte Daprà had alluded to these ominous shapes in her essay in Italian and German:

“Rosa presents an almost inexhaustible repertoire of rock shapes… which, because they have been softened by the [natural] elements, have taken on anthropomorphic or zoomorphic shapes.” [30]

These zoomorphic forms were demonstrably created by Salvator Rosa on the basis of observations from life and from nature, with modifications inspired by his interest in the supernatural. As we shall see below in the pages that follow, the respective optical illusions of artists and of Nature comprise the central themes of this and other paintings by Rosa although his interest in this theme has mostly gone unnoticed.

In the Grotto, the wolf’s ghastly head is topped by the broken skull of a horse that corresponds to Rosa’s several etchings of this macabre motif.[31] Close by, at right, the other limestone crag [Ital. sperone], has been transformed by the painter into the indistinct form of a wild creature with a muzzle, which appears to gaze thunderstruck at the hostile arrival of the wolf. (Fig. 6)

This brutish animal, part dog and part badger [Ital. tasso]), wears a furry collar of the dark green slimy moss typical of grottos. The photograph of this detail fully displays the spontaneous bravura of Salvator Rosa’s brushwork, which no copyist or follower could have imitated.[32] The zigzag rhythms of the brushstrokes seem abstract when seen close-up and yet astonishingly realistic from a distance. The mingled contrasts of sandy and grey pigments are distinctive to Salvator Rosa, who preferred these tones over all others, especially in his later years.

With his usual inclination for visual sleights of hand, Rosa painted the intertwined letters of his monogram SR in relief on the roughly sketched body of this brutish animal with a muzzle (Fig. 7).

Upon inspection in person with Dr Trezzani, this signature is executed with painstaking skill and indisputably integral with the surrounding impasto. As a sign of the advances in technology this close-up photograph, taken by a mobile telephone (iPhone 13 Mini), is the first ever published of this important signature. Rosa was justly proud of his intricate monogram and signed his works more often than was customary for artists of his generation. Clearly legible and yet difficult to copy exactly, the slightly larger S serves as a subtle paraph, overlapping the R in an unusual way. (Fig. 8).

Here is a close-up comparison with the same monogram on an etching from Rosa’s Figurine series, mainly of solders, of 1655.[33]

Rosa’s depiction of ferocious animals magically conjured out of the dark depths (and mostly hidden) of a subterranean grotto could have been foreseen as the culmination of his experimental paintings of necromancy during the 1640s in Florence, the capital of occult philosophy.[34] Such ungodly subjects were unimaginable in Rome, the Papal See, where Rosa yearned to attain both fame and the highest rewards for his paintings. As we deepen our exploration of Grotto, we shall see that Rosa chose to make these rocky transmutations of a wolf and a dog/badger readily recognizable since they are meant to resemble examples of Nature’s own handiwork in corroded limestone. As we shall see, Rosa hid a far greater illusion beneath the shadows.

For purposes of comparison, it will be useful to look at a prior demonstration of Rosa’s fascination with magical grottoes. One of his earliest works in Florence, The Temptation of Saint Anthony, c. 1645, in the Palazzo Pitti (Fig. 9),conforms to the tradition of ancient grottoes as battlegrounds for clashes between evil spirits and sanctity.[35]

As portrayed in numerous paintings by David Teniers II and earlier Netherlandish and German artists, the excruciating temptations suffered by Saint Anthony of Egypt were a fearsome assault by hordes of repulsive, if ineffective, demons.

Rosa, however, departed from this prevalent iconography almost entirely. Instead, he chose the erudite alternative of a fourth century biography by Athanasius of Alexandria, who wrote that the saintly monk was knocked down and almost killed by the Devil. This is the awful scene imagined by Rosa. The fallen saint holds up the Cross to defend himself against an evil demon with the head of a dragon, who lunges down on him like a skeletal bird of prey. The artist’s source for this creature would have been recognized by his patron, Giovan Carlo de’ Medici,[36] and by every other art collector in Florence, as a conspicuous borrowing from the Incisioni di diversi scheletri di animali, a series of scientific etchings of the bone structure of birds and animals made by Filippo Napoletano during his residence in Florence, 1617-1621.[37] Similar skeletal monsters appeared in at least two paintings by Napoletano.[38] Instead of kneeling in prayer, Anthony’s prostration on the ground is a direct reference to the Athanasius biography. Seeking to impress his Medici patron, Rosa introduced an additional hidden symbolism that had never been seen in the story of St Anthony. The contorted pose of the tormented saint provides the key to this symbolism. It has never previously been noticed that Rosa borrowed the pose, in reverse, of the fallen saint from an earlier and renowned painting of a martyrdom: The Martyrdom of Saint Matthew by Caravaggio in the Contarelli Chapel (c. 1600) in San Luigi de’ Francesi, Rome (Fig. 10).

After being knocked to the ground, both Rosa’s St Anthony and Caravaggio’s St Matthew, turn towards their assailant with arms outstretched in the form of the Cross. As St Matthew reaches up to receive the martyr’s palm, his upraised hand touches the Cross on the altar frontal.[39] Rosa’s St Anthony does the same, holding up a Cross to defend himself from the evil monster. There are many other correspondences between the two saints, including the unusual composition which draws our eyes first to the assailant and then to the saintly victim on the ground. The multitude of borrowings from Caravaggio makes it clear that Rosa intended them to be recognized and appreciated by the cognoscenti at the Medici court, and surely they were.[40] That Rosa had this intention is demonstrated by St Anthony’s cupped hand near the small stream of water on the floor of the grotto, a gesture that is otherwise inexplicable.

-

New Light on the Three Figures: a Soldier, a Dwarf and a Sorceror

Since 2008 and in all publications until today, the three dimly visible figures in the Grotto have usually been described as soldiers because of the tiny metallic reflections from their pieces of armor. Before proceeding to the new readings, it will be useful to describe this dark, almost indecipherable painting as it was perceived by everyone since its rediscovery. To begin with, a patch of blue sky high on the left side of this painting marks the entrance to the subterranean grotto. Through this natural window a thin ray of daylight descends into the abyss, randomly touching massive spurs of rocks shrouded in the gloom. At the center of the cave, a craggy column of limestone leans far forward as if frozen in the act of crashing down. This frightening sight is observed by two “soldiers” who appear to have taken shelter inside a hollowed-out boulder at lower left. The only light on their murky figures are the minute reflections on their metal armor. Little else was detectable with the naked eye, and the same was true for a third shadowy figure whose presence at upper right, seemingly perched on top of a rock formation, is likewise betrayed by a few staccato flashes on metal. The ambiguities caused by the heavy darkness explain why the painting was heretofore titled imprecisely, Soldiers in a Grotto.

With the benefit of visual tools that were unavailable to scholars ten years ago, we are now able to identify the figures with unprecedented precision, which allows us also to deduce the purpose of their visit to this infernal grotto. Given the opportunity to re-examine the Grotto last May, I photographed each of these three amorphous “Soldiers”. Through the modern magic of high-resolution digital photography, we now clearly see that only one of them is definitely a soldier (Fig. 11).

At left in the foreground, he stands inside the boulder on the floor of the grotto, dressed in full armor and holding a halberd. The tall soldier carries himself with the confident air of a commander as he looks down at his smaller companion, a short, stout man, who appears to be a court dwarf splendidly dressed in a red oriental cap with a metal brim and a plume. His breastplate reveals the thick sleeves of a red jacket.[41] This presumed dwarf makes a sweeping gesture towards the alarming wolf creature emerging from the rock, which suggests that he is the soldier’s guide to this eerie underworld. Neither of the two men seems at all afraid of the unearthly spectacle. Indeed, both the soldier and his guide stand nonchalantly with an arm akimbo, evidently satisfied to witness the occult ceremony. Now that they are visible, we can see that Rosa appropriated this pair of onlookers from the Workshop of the Alchemist, 1618/19, Palazzo Pitti, by Filippo Napoletano, which must have been one of Rosa’s favorite paintings, judging from its salient influence on his Florentine paintings of witchcraft (Fig. 12).

In the lower right corner, Filippo inserted two figures in courtly dress enjoying their privileged visit to this bustling and untidy alchemical laboratory. The two unidentified visitors are an old man wearing a black cap, who is accompanied by a dwarf; they both extend their open hands in appreciation of the mysterious goings-on. The explicit analogy between Rosa’s pair of onlookers (soldier and dwarf) and Filippo’s pair of onlookers (courtier and dwarf) is testament to the Grotto’s connections with Rosa’s necromantic studies in Florence. Marco Chiarini suggested that Filippo based his alchemical laboratory on the Casino di San Marco, which belonged to Cardinal Carlo de’ Medici, a passionate alchemist (reputedly a magus), who lived above the Casino di San Marco, and was the uncle of Rosa’s patron, Giancarlo de’ Medici.[42]

Further technical evidence of Rosa’s authorship of the Grotto is found in the presence of the same staccato flashes of light on black armor in other paintings, for two examples, the Battle between Christians and Turks, c. 1641, in the Palazzo Pitti, Firenze, from his Florentine period, and his Rocky Landscape with Soldiers and a Huntsman in the Louvre, datable c. 1652 (Fig. 13).[43]

Similar metallic reflections lead our eyes to the third “soldier”, very dimly seen, perched on top of a jagged cliff on the opposite side of the grotto. This isolated man has gone unnoticed by many historians or was assumed to be a third soldier. Examination of an enlarged high resolution photograph, here illustrated (Fig. 14), reveals him as an angry sorcerer with a round cap like a fez, who gestures fiercely as he reads by candlelight from some large books.[44]

This sorcerer is arguably the artist’s most astonishing accomplishment in the Grotto since his figure is entirely composed of the same brushstrokes that delineate the dog/badger’s face on the limestone spur. The sorcerer’s face is the eye of this savage beast. The round sleeve of the sorcerer’s jacket is the animal’s muzzle. His pile of crumpled books do double duty as rubbery ridges of the canine mouth, which, depending on the viewer’s perspective, unexpectedly metamorphoses before our eyes into the sorcerer – and vice versa. If we assume that Rosa painted the tall soldier and his dwarf-guide as real humans, neither illusions nor spirits, the most likely reading of the sorcerer would be as a human magician who possesses the powers to summon and then hide himself inside an illusion. The discovery of a magus casting spells inside a grotto does not come as a surprise, of course. Rosa’s oeuvre – and particularly his paintings doused in darkness – abounds with sorcerers and witches who perform their rites while immersed in their occult books and scrolls. Specifically characteristic of Rosa, by the way, is his arrangement of his trio of actors on different levels so that they speak their lines either up or down, as the case may be. With few exceptions in his career, Rosa consistently avoids depicting people speaking face to face.

It is a sign of the painter’s pictorial powers that as soon as the viewer becomes aware of the sorcerer, his hidden figure becomes clearly discernible despite the inky darkness.[45] This elusive tour-de-force of anamorphism has never previously been noticed since the painting’s rediscovery and exhibition in 2008. Of the three “soldiers”, the sorcerer was the most visible, and yet he was the most overlooked by writers, simply because Rosa had hid him in an anamorphic disguise of an animal head. The revelation of the sorcerer performing incantations leads us to understand that the wolf and dog/badger were not selected at random: from the most ancient writings up until and through the seventeenth century writings witches were associated with both wolves and dogs.[46]

It is perhaps significant that Rosa impressed his monogram SR in the thick impasto a mere ten centimeters below the sorcerer. As is the rule in Rosa’s paintings of wizardry, the mood of the Grotto is indubitably menacing but there is a whimsical element about the three characters (including the evil sorcerer) that makes them seem slightly comical notwithstanding their frightful adventure. Rosa’s representations of witchcraft never suggest that he approved of their abhorrent rituals, although he undeniably found them interesting.

As bizarre and unexpected as the various optical illusions in the Grotto might seem in the context of Italian painting, numerous precedents can be found in Netherlandish and Germanic paintings and engravings, many of which scholars have rightly shown were known and imitated by Rosa. One pertinent example that has not previously been associated with Rosa is a widely circulated engraving invented by Pieter Bruegel the Elder in 1565, in which Saint James confronts the powerful Magus Hermogenes in his ugly dwelling crammed with demons and monsters. (Fig. 15). [47]

In the center of the diabolical activities, one sees a grimy underground cranny that displays optical illusions later employed in Rosa’s Grotto. First, there is the illusion of a human metamorphosed into an animal: to wit, the conjurer who leans over a book is transformed into the head of a rabbit. Second, the figures in the deep shadows appear as flat, immaterial shadows.

Epilogue, Four Appendices and Suggestions for Future Research

In the early phase of this research, before it was known that the three soldiers dimly glimpsed in the Grotto were instead one soldier, a dwarf and a sorcerer, the opening pages of the paper (Prologue and Sections I-II-III) were dedicated to studies of the historical and cultural foundations of Salvator Rosa’s lifelong fascination with coastal rock formations and dark grottoes, dating back to his youth. The grotto itself appeared to be the subject of the painting. Particular attention was also given to the problem of Rosa’s lost painting of Il Sasso as first presented in Luigi Salerno’s groundbreaking analysis of 1991. In her publication of the Grotto in 2008, Brigitte Daprà had ascribed the Grotto to Rosa and suggested that the lost Sasso might be related in some way to the Grotto.[48]

The three Appendices I-II-III, v. infra, were originally sections in the main body of this paper, but were metamorphosed into appendices in order to make space for the discoveries of the soldier, dwarf and sorcerer. Appendix I illustrates four paintings by Philipp Peter Roos (Rosa da Tivoli) and Alessandro Magnasco that are directly inspired by the Grotto.

Appendix II contains two inexplicably overlooked references to an 18th– and 19th-century Neapolitan provenance for the Sasso, including an observation that Rosa’s Sasso resembles ‘dogs’. Appendix III illustrates five paintings in which the anthropomorphic and zoomorphic rock formations are clearly visible.

Appendix IV contains a passage in Rosa’s Strega poem, which was noted as possibly related to the Grotto in the first phase of research, then put aside and forgotten because a precise connection was lacking. Only now, as this paper is going to press, do I realize that the sorcerer’s magical incantations of the monstrous wolf and dog/badger constitute a convincing link between his poem and his painting. Ut poesis est pictura.

In Conclusion.

New research into Salvator Rosa’s Grotto, extending beyond the limitations of an exhibition catalogue entry, has confirmed the attribution advanced in 2008 by Nicola Spinosa and Brigitte Daprà. Under close inspection the palette and virtuoso brushwork of the Grotto are recognizable as the artist’s inimitable hand. The originality and expressive impact of the necromantic subject — A Soldier’s visit to the Grotto of a Sorcerer — is itself an affirmation of the mind and brush of Salvator Rosa. The possibility that the Grotto is identical to the lost Sasso is considerably supported by the circumstantial evidence published in this paper, especially in Appendices I and II. Perhaps the progress made by this research show the way to definitive proof, as yet unknown or overlooked.

Appendix I The Artistic Legacy of the Grotto

If Rosa’s scandalous Sasso of 1653 was as famous as the artist believed it was, it is safe to assume that other painters made copies and variations of it. No such copies have been found for the simple reason that the appearance of the Sasso is unknown. On the other hand, new research has identified many copies of the Grotto. These copies by leading painters tend to support the attribution of the Grotto to Rosa. They do not constitute proof, however, that the Grotto is the same painting called the Sasso that Rosa exhibited at the Pantheon in 1653. It is too soon to consider the question closed.

Of the five variations of the Grotto published in this Appendix, two are universally ascribed to Philipp Peter Roos (Frankfurt 1655 – 1706 Rome), a third, similar painting, passed through the Paris art market in 2011 with an attribution to Roos that has not yet been confirmed. The final two paintings are a pair of landscapes universally ascribed to Alessandro Magnasco (Genoa 1667-1749). Magnasco was a decade younger than Roos, who was called Rosa da Tivoli in recognition of his long residence in Tivoli, a day’s journey from Rome. Their careers are believed to have overlapped in Florence around 1700. Unfortunately, there is no consensus as to the dates of these paintings by P.P. Roos and Alessandro Magnasco.

The first two variations on the theme of the Grotto by Rosa da Tivoli were conceived as pendants and were acquired by the Hermitage in St Petersburg in 1930.[49] The measurements of these upright compositions, 97 x 81 cm and 97 x 82 cm, are roughly the same as the Grotto, 94 x 78 cm. The Marine Grotto with a Shepherd on a Horse (Fig. 16) is the most interesting picture of the pair due to its central motif: a massive rock formation like a smiling sphinx, or giant dog, that looms inexplicably over a shepherd on horseback.

The resemblance to the menacing zoological rocks in the Grotto is unmistakable. At upper left, the oblong patch of blue sky is another borrowing from Rosa. As a work of art, Roos’s monochromatic evocation of a mysterious atmosphere with deep shadows is an impressive homage to Salvator Rosa’s invention that overwhelms Rosa’s bucolic painting of a shepherd on horseback pausing to water his sheep.

The pendent Landscape with a Waterfall (Fig. 17), also in the Hermitage, is similarly haunting in its overt borrowing of brooding rock faces from the Grotto and other rocky landscapes by Rosa.

In the foreground, one sees the silhouettes of a fisherman and his dog standing in front of a turbulent cascade of spidery water. At right, one see the opening of a grotto in the midst of rock formations inspired by Salvator Rosa’s signature skulls. (See Appendix 3.I).[50] Rosa da Tivoli rocks seem soft and spongy and his water less realistic than Salvator Rosa’s. The somewhat crude execution of these two paintings suggests that these are among Roos’s earliest works after his arrival in Rome in 1677. It may be that Roos’s famous nom de plume, Rosa da Tivoli, might also reflect his early emulation of Rosa’s landscapes and not only Roos’s residence in Tivoli.

The third painting attributed to Philipp Peter Roos is an elegant variation on the Grotta Marina in the Hermitage, executed in a more polished technique and a more subtle palette of colors (Fig. 18)

The painting appeared at auction in Paris in 2011.[51] It will be necessary to examine the painting in person in order to be certain of the attribution to Roos. Some passages in the photograph resemble the hand of Alessandro Magnasco.

Like Rosa da Tivoli, Alessandro Magnasco was born too late to have encountered Salvator Rosa in person, but his admiration for older master’s landscapes was deeper and more lasting. Today, Magnasco is generally considered a close follower of Salvator Rosa, even to the extent of sharing a restless personality, a spirito inquieto. Magnasco’s two variations on the painting of the Grotto were slighter larger, 104.7 x 97.2 cm, than P.P. Roos’s pair in the Hermitage. There are several other visual connections between these paintings that call for further examples of the originals. On the one hand, it is evident that both artists admired and were inspired by Rosa’s Grotto; on the other hand, that it appears that Magnasco was also inspired by Roos’s example to paint two pendants with rural figures.

As was the case with Roos, Magnasco’s Shepherds is the most interesting of the pair due to its central motif: a massive rock formation that resembles a horse leaning ominously over a camp of shepherds who seem to have camped in a mysterious grotto.[52] The resemblance to the menacing rock formations in the Grotto is unmistakable, although much less frightening. Rosa’s wolf crag has been transformed into a horse, or possibly a dragon skull that leans in to look at the shepherds in the grotto. This skull is mirrored by two flattened skulls on the adjacent cliff that also reflect Rosa’s motifs of animal skulls. The tall tower in a castle wall on top of that steep cliff is a typical Rosa motif that also appeared in the picture by Roos.[53]

Magnasco’s two paintings were separated many years ago and have only recently been understood as pendants.[54] (Fig. 20).

The Fishermen in a Grotto in Budapest displays a similar band of shepherds and sheep camped on rocks in a grotto. Some hanging rocks at the top of painting display flattened animal skulls in the style of Salvator Rosa and comparable to the formations in the Grotto.

Magnasco is reputed to have adapted other works by Rosa. He was presumably in Florence, ca. 1704, when he painted a copy of Rosa’s Temptation of St Anthony in the Palazzo Pitti, Florence (Fig. 21), in which he substituted some ruined arches for Rosa’s grotto.[55]

Appendix II Two Overlooked References to the Sasso in Naples between 1742 and 1892

In his commentary to his groundbreaking collection of Poems and Letters by Salvator Rosa,[56] Giovanni Alfredo Cesareo called attention to the Rosa’s painting of the Sasso as described in Rosa’s verses in the Satire Invidia. Cesareo noted that the Sasso was seen a century later in 1742 in the collection of the Duke of Laviano in Naples by Bernardo De Dominici, who described it as a beautiful “painting of a white rock composed with great skill.” Cesareo accepted De Dominici’s unsubstantiated statement that the Duke di Laviano had acquired the painting directly from Salvator Rosa himself around 1646. For Cesareo, therefore, the Sasso was never lost, because one hundred and fifty years after De Dominici, in 1892, when Cesareo published his book, quoting De Dominici (1742, vol. II, p. 244) accurately and at length, the Sasso was still in the Laviano palace in Naples where Cesareo also saw it. Fortunately for our purposes, Cesareo admired the Sasso and described it in a way that corresponds to the Grotto:

“a painting of the Sasso that calls to mind dogs (cani), which was in fact the intention of the implacable painter, who boasted of it a few months later in his satire Invidia [Envy]”.[57]

- De Dominici, “Vita di Salvator Rosa, Pittore, e Poeta, e de’ suoi Discepoli”, in Vite de’ pittori, scultori ed architetti napoletani, Napoli, 1742, p. 224. “L’ultima volta che il Rosa venne in Napoli fu nella fine dell’anno 1646, e vi lavorò molte opere, alcune per commessioni avute da Roma, altre per dilettanti, che allora fiorivano nella nostra Città; come ne fan testimonianza i quadri, che ora si veggono in casa del Marchese Biscardi, e del Duca di Laviano (appresso al quale fra gli altri vedesi quello, ove è dipinto un sasso bianco con maravigliosa arte di accordo)”…

- A. Cesareo, 1892, Vol. I, p. 49. “Il primo a narrare quelle gesta del Rosa fu Bernardo De Dominici, circa un secolo dopo; e i particolari ond’egli le adorna rivelano, meglio che non ricoprano, l’inganno. Riporto intero il testo di Dominici. «Conviene a noi ora raccontar l’occasione per la quale il Rosa fece di nuovo ritorno a Roma… L’ultima volta che il Rosa venne in Napoli fu nella fine dell’anno 1646, e vi lavorò molte opere, alcune per commessioni avute da Roma, altre per dilettanti, che allora florivano nella nostra Città; come ne fan testimonianza i quadri, che ora si veggono in casa del Marchese Biscardi, e del Duca di Laviano (appresso al quale fra gli altri vedesi quello, ove è dipinto un sasso bianco con maravigliosa arte di accordo«…””[58]

- A. Cesareo, 1892, Vol. I, p. 72 [re: the critics’ attacks on his poetry…] “Il Rosa rispose da prima con una trovata bizzarra. Il giorno di San Giovanni Decollato del 1652 [sic] espose alla Rotonda il suo quadro del Sasso, ove un sasso è dipinto con suprema efficacia di tòno, che poi fu acquistato dal duca di Laviano da Napoli (Nota 3). Il sasso per sè medesimo richiamava al pensiero i cani; e tale fu a punto l’intenzione del maligno pittore, che qualche mese dopo se ne vantò nella satira dell’ Invidia (v. 538 e segg.):” «… Ma per tornare a te, giammai discosto/ Non mi sei stata a la Rotondo un passo/ Quando vi fu qualche mio quadro esposto. Ond’io, ch’ al tuo latrar mi piglio spasso/ Acciò che dentro tu vi spezzi i denti,/ Quest’Anno non vi ho messo altro ch’un sasso. … Il quadro del Sasso, se da un lato levò gran clamore di risa contro [continues on p. 73] i malcapitati calunniatori del Rosa, dall’altro concitò e acuì la loro ira, e la rese più feroce e più formidabile…”

- A. Cesareo p. 72, Note 3. “Cfr. De Dominici op.cit. p. 224. Il De Dominici, e ognun può vedere con quanto discernimento, avendo scoperto, un secolo dopo, il quadro del Sasso in casa Laviano a Napoli, ne dedusse che il Rosa dovè trovarsi in patria al tempo della rivoluzione di Masaniello.” Il quadro del Sasso, se da un lato levò gran clamore di risa contro i malcapitiati calunniatori del Rosa, dall’altro concitò e acuì la loro ira, e la rese più feroce e più formidabile.

Appendix III Five Paintings by Salvator Rosa with Antropomorphic and Zoomorphic rock formations

Appendix III illustrates five landscapes in which the rock formations are easily discerned even in photographs. All dates are from the catalogue by Luigi Salerno, L’Opera completa di Salvator Rosa, Milano, 1975, [LG 1975].

“è certa l’autografia della tela in esame, ove permane sia nei volumi che nella resa tonale una certa morbidezza alle opere paesistiche del periodo fiorentino…”.

This painting was reported stolen on 11 March 2020.

““Tali dipinti sono caratterizzati dalla fattura sommaria che costituisce l’ultima fase stilistica del Rosa.”

The painting is pendant to a Marine (LG 1975, n. 149) in the Musée Condé, which also depicts zoomorphic creatures hidden in coastal rocks.

“Certamente opera molta tarda.”

The Epinal landscape is among Rosa’s most praised compositions. Helen Langdon described in unprecedented detail the anthropomorphic rock face:

“The hermit is immersed in a book as he sits precariously on a slab of rock that resembles a thick book. ‘Face to face’ with him, is a giant rock mass that resembles the head of a giant watching him intently, benignly as opposed to threateningly, a face on which we can discern two eyes, a small mouth and a bushy brow comprised of soft foliage.”

One of a pair of small landscapes by Rosa, which taken together comprise a narrative of the dangers of the sea.

The presence of monstrous faces in the mountains and cliffs by Rosa derive from the iconography of Scylla and Charybdis. Three sea monsters on the rocky cliffs of a inlet are inscribed in a blue rectangle.

The hermit appears to seat beneath a rock cliff that resembles the head of a monstrous horse. The painting was first published by Luigi Salerno in 1970.

Appendix IV An Anticipation of the Grotto in Rosa’s poem, LA STREGA

While reading through Salvator Rosa’s writings in search of glimmers of light for the mysterious Grotto or for Rosa’s equally mysterious lost painting of 1653, Il Sasso, I chanced upon some lines of poetry in Rosa’s outrageous poem La Strega [The Witch], written in Florence around 1646 when he was most immersed in imaginative paintings of the ceremonies of witchcraft. It is revealing, and paradoxical, that Rosa wrote his poem in an acerbic burlesque style that mocks his subject. The appalling heroine is a witch named “Phyllis”, who relates exuberantly the horrendous spells she intends to inflict on her unfaithful lover. Phyllis begins her tirade with an alarming description of the subterranean grotto where she will unleash the ferocious incantations.[59] “In this pitch-black cave, where the sun’s rays never reach, by the powers of the Tartareans, I will summon the infernal hordes…” [Ital: In quest’atra caverna / Ove non giunse mai raggio di sole /Da le tartaree scuole / trarrò la turba inferna…”. Tartarus (as in “Tartarean”) was the primordial Greek god who ruled over the lowest and darkest pit of the Underworld.[60] He possessed magic powers to control both souls and demons. In the early stage of research into the Grotto, I could not find a direct connection with Rosa’s painting of three murky soldiers immersed in an impenetrable darkness underneath the strange rock formations of a wolf’s head, the skull of a horse, and a zoomorphic mixture of dog and badger that had been inexplicably overlooked. I therefore filed away the La Strega reference in my laptop. But after the discovery of the sorcerer who must have called up these illusions from the limestone rock, I realized that Rosa’s Witch of circa 1646 had contained this anticipation of his painting of the “Soldier and a Dwarf visiting a Sorcerer’s Grotto” of circa 1650-55.

Now re-reading the poem, I soon found that those breathtaking lines from La Strega were significant to Rosa and were not chosen at random. His appreciation of them was such that he lifted them directly from the Gerusalemme liberata (IV, 3.17-24) ), the epic poem of 1581 by Torquato Tasso.

Call the inhabitants of the eternal shadows. / The hoarse sound of the infernal trumpet: / The other spacious caves tremble, / And the air, blind to that noise, rumbles.

Chiama gli abitator dell’ombre eterne / Il rauco suon della tartarea tromba: / Treman le spaziose atre caverne

The only part of the verse by Rosa himself was the description of the grotto, “where the sun’s rays never arrive,” “Ove non giunse mai raggio di sole”, which anticipates the interior of the Grotto he painted a few years later.

[1] Salvator Rosa, Soldiers in a Grotto (Soldati in un antro roccioso), Pandolfini, Firenze, 23 May 2023, lot 42, 94 x 78 cm, signed SR intertwined in relief, Private collection. This inaccurate title will be abbreviated to the Grotto in this article. See figure 12 and 13 infra.

[2] The chronology of Rosa’s activity in the 1640s was long disputed. It is now clear that he travelled throughout his “Florentine period” of service to Cardinal Gian Carlo de’ Medici, which began in 1640.

[3] Letter, 12 May 1651, “…poiché havendo Roma appreso ch’io son stravagantissimo nell’inventioni, bisogna corrispondere quanto più sia possibile.” In Floriana Conte, “Per Salvator Rosa da Firenze a Roma: agenda”, in Il ritratto, Atti del Seminario di Studi (Bari, 11 giugno 2007), a cura di R. Stefanelli, P Guaragnella, , M. Stomeo, Roma, Aracne, 2008, p. 41. Rosa’s biographer Giovan Battista Passeri wrote that he “wanted that new things of his should be seen every year at the feasts of the Rotonda and of S. Giovanni Decollato” [egli “voleva che alle feste della Rotonda e di S. Giovanni Decollato ogn’anno si vedessero di suo cose nuove.”] Vide J. Hess, Die Kunstlerbiographien von G. B. Passeri, Leipzig-Wien, 1934, p. 391.

[4] A. De Rinaldis, Lettere inedite di Salvator Rosa, Roma, 1939, p. 26, 57-59. Cf. L. Salerno, ‘Due Momenti singolari di Salvator Rosa’, Artibus et Historiae, 23, xii, 1991, pp. l21— 8.

[5] These quotations are from Rosa’s Satire VI, Invidia, 550-553, which he began to write in the summer of 1652 and finished by March 1653, although some sources give a later date of 1654. L. Salerno, ‘Due Momenti singolari di Salvator Rosa’, Artibus et Historiae, 23, xii, 1991, p. 121.

[6] Salvator Rosa, Landscape with Hermits, Christies, London, 1990, lot. 4.

[7] L. Salerno, 1991, p. 121, fig. 1. “Vero protagonista della composizione è un grande masso di pietra vicino al quale due piccoli eremiti sembrano aggiunti solo per dare un minimo di accettabilita al soggetto. My thanks to John Hawley of Christies for his confirmation that the current location is unknown. Rosa’s paintings of two hermits in a rocky wilderness remain to be studied in depth, as they often suggest broadly painted narratives in their rock formations, e.g. those like stacks of books, and blasted trees with horned branches and so on.

[8] This hypothesis seems not to reflect Rosa’s brief description. Jonathan Scott, Salvator Rosa: his life and times, Yale University Press, New Haven-London Yale Univ Press, 1995, pp. 103 and 244 note 22. Cf Hannah Lee Pamela Segrave, “Conjuring Genius: Salvator Rosa and the Dark Arts of Witchcraft”, PhD dissertation, 2022, University of Delaware, online udspace.udel.edu. p. 438 note 16.

[9] A.C. Hoare, Salvator Rosa as “Amico Vero”: The Role of Friendship in the Making of a Free Artist,” University of Toronto, PhD dissertation, 2010, p. 153, note 298: “The “sasso” was either an actual painting of a stone, as yet unidentified, or simply a metaphor.”

[10] B. De Dominici, 1742, v. 2, p. 215, “…disegnar massimamente le vedute della bella riviera di Posillipo e quelle verso Pozzuoli, quasi tanti esemplari prodotti dalla natura.”

[11] S. Rosa, Soldati che giocano a Carte, Roma, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Cordini, 30 x 23 cm; Rosa, Paesaggio con sue Popolani, Roma, Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Cordini, 30 x 24. cm; L. Salerno L’opera completa di Salvator Rosa, 1975, nn. 2 e 3

[12] The anthropomorphic and zoomorphic rock formations in Rosa’s landscapes are often difficult to discern in photographs. See Appendix III for a few paintings in which they are easily discerned and interpreted. Helen Langdon has written definitively of the symbolism of the rocks in Rosa’s Landscape with Hermit in the Musée de Épinal (Salerno 1975, no. 259): “The hermit is immersed in a book as he sits precariously on a slab of rock that resembles a thick book. ‘Face to face’ with him, is a giant rock mass that resembles the head of a giant watching him intently, benignly as opposed to threateningly, a face on which we can discern two eyes, a small mouth and a bushy brow comprised of soft foliage”.

[13] In classical mythology natural caves with springs were venerated on the assumption that they were the home of nymphs and the Muses. Cf. John Dixon Hunt, “Emblem and Expressionism in the Eighteenth-Century Landscape Garden”,

Eighteenth-Century Studies, Vol. 4, No. 3, (Spring, 1971), p. 296.

[14] Aeneid, 6.124-129. Cf. Naomi Miller, Heavenly Caves: Reflections on the Garden Grotto, New York, 1982, p. 87.

[15] The interest in this subject was given impetus in Florence by Filippo Napoletano’s presence, 1617-21, whose spectacular painting of Aeneas and the Sibyl in the Underworld was first recognized by Marco Chiarini, Appunti su Filippo Napoletano e la pittura nordica, in ‘Ricerche sul ‘600 napoletano’, 1996, fig. 12 a p. 50, pp. 60, 62 n. 7.

[16] Wright of Derby, Grotto by the Seaside in the Kingdom of Naples with Banditti, Sunset, 1778, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston.

[17] Pico della Mirandola, Conclusiones magicae, no. 10: Quod magus homo facit per artem, facit natura naturaliter faciendo hominem.” Cf. L. Salerno, “Il dissenso,” 1970, “The path they followed seems to be clearly traceable from the Renaissance right down to the period of Illuminism and Neoclassicism.”

[18] J.P. Richter, Literary Works of Leonardo da Vinci, 1930, no. 1151. Translation by E. Wind , Pagan Mysteries of the Renaissance , Penguin , Harmondsworth , 1967 , p . 111.

[19] L. Salerno, Salvator Rosa, Milan (Edizioni per il Club del Libro), 1963, pp. 39 and 43, singled out Della Porta’s Magiae naturalis, sive, de miraculis rerum naturalium [“Of natural magic, or of the miracles of natural things”] as a primary influence on Rosa. Most scholars agree that Rosa knew Della Porta’s writings on the occult. Two useful studies of Della Porta are: the Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (online) and W. Eamon, “A theater of Experiments: Giambattista Della Porta and the Scientific Culture Renaissance Naples”, in Borrelli A., Hon. G., and Zik Y., (eds), Giambattista Della Porta (1535–1615). A Reassessment, Switzerland, 2017, pp. 11–38: Accorting to these sources, “Della Porter was considered a natural magician because he had discovered many of the secret miracles of nature”; he created “a stage where nature performs” at various levels, unveiling its tricks, and a metaphysical space in which the principles of magic are demonstrated. Porta’s magus is a decidedly male figure who unites the physical dexterity of the trickster, the experience of the alchemist, the erudition of the humanist, the astrologer’s command of mathematics, and the intuitive knowledge of the psychic medium in order to embody a superhuman, ideal man capable of manipulating everything and everybody (G.B. Porta, Magiae 1558: bk. 1, ch. 2). By Rosa’s time, Della Porta had become discredited for his experiments with magic, although even the Jesuit, Athanasius Kircher found his experiments interesting.

[20] In 1970, Luigi Salerno published a valuable article on Filippo Napoletano, Salvator Rosa, and other prominent painters in Rome, Naples and Florence with regard to their roles in two new artistic movements that arose in the 1640s: the philosophical-scientific world, especially as revealed in magic; and stoic philosophy (“Il dissenso nella pittura…, in Storia dell’arte, gennaio-marzo 1970). These artists, Salerno noted, were aware of their descent from Caravaggio and his followers, as well as the naturalistic Northern artists like Pieter Brueghel the Elder. Angelo Caroselli (1585-1652) and Rosa were the boldest painters of magicians and witches, which were illegal subjects in papal Rome. A central participant in the tendences was a prolific scientist, Athanasius Kircher, whose writings have been profitably searched by Helen Langdon, Christina Volpi and other art historians, for parallels with Salvator Rosa’s thought.

[21] See Note 1, supra.

[22] Nicola Spinosa, ed., Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia, Napoli, Museo di Capodimonte, 18 aprile – 29 giugno 2008, with entry by Brigitte Daprà, pp. 214-215, no. 69,

[23] X. F. Salomon, review of the exh. cat. Salvator Rosa: tra mito e magia, Capodimonte, Napoli, in Burlington Magazine, July 2008, p. 495: no.69 was one of eleven paintings considered dismissed …”weak works and their attribution to the artist is unconvincing.”; C. Volpi, Salvator Rosa (1615-1673) “pittore famoso”, Rome, Ugo Bozzi Editore, 2014, p. 99, no. 15, “Opera più tarda.”

[24] Peter Forster, Elisabeth Oy-Marra, Heiko Damm, in “Caravaggios Erben – Barock in Neapel”. “Caravaggios heirs – baroque in Naples“, Museum Wiesbaden, October 2016 – February 2017, pp. 400-401, n. 117.

[25] Rosa’s landscapes rarely offer a view from a mountaintop, unlike two earlier and influential landscapists from the north, Brueghel the Elder and Paul Bril. Cf. J. Scott, Salvator Rosa: his life and times, Yale University Press, New Haven-London Yale Univ Press, 1995, p. 202.

[26] For color illustrations see: Salvator Rosa, Grotta con cascata, Palazzo Pitti, in: L. Salerno, 1975, tav. XIX; and in N. Spinosa, ed., Salvator Rosa tra mito e magia, exh. cat. Naples, Paesaggio con arco naturale, no. 59.

[27] See Note 1, supra. The Grotto was consigned from an unidentified private collection and was acquired by another private collection.

[28] L. Trezzani, in Pandolfini, 2023, p. 76., “Non è certo un caso che nel 1653 Salvator Rosa scegliesse un paesaggio di roccia per sfidare il mondo academico esponendo a Roma un dipinto intitolato Il Sasso: un’occasione per dimostrare la propria superiorità tecnica, oltre che il disprezzo per la gerarchia stabilità tra generi pittorici a partire dal soggetto”.

[29] Daprà and Trezzani date the Grotto to the 1660’s; in my opinion, the painting retains Florentine traits, suggest a date in the early 1650s.

[30] Brigitte Daprà, 2008, p. 214; (2016-2017, p. 401): “Rosa esibisce un quasi inesauribile repertorio di forme di rocce…perché ammorbidite dalle intemperie, che spesso assumono anche forme antropomorfe o zoomorfe. Questo dipinto, siglato sul masso, in basso a destra, e raffigurante un antro roccioso, potrebbe essere il risultato finale di una serie di studi dal vero…”

[31] Cf. the ox and horse skulls published as studies for Rosa’s painting Democritus in Meditation in Copenhagen, which he exhibited at the Pantheon in 1651/1652. R.W. Wallace, The Etchings of Salvator Rosa, Princeton, 1979, cat. 105 and 106.

[32] Rosa used the same technique of thick pigments, molded as if clay, in his representation of the interior of Mount Etna in his painting of The Death of Empledocles, ca. 1666, private collection. Helen Langdon described this picture as “man’s desire to lose himself in the immensity and violence of natural forces” in Salvator Rosa, exh. cat., Dulwich Picture Gallery, 2010, p. 213.

[33] R.W. Wallace, The Etchings of Salvator Rosa, Princeton, 1979, cat. 76, “Man Standing Arm Raised Pointing toward Left”.

[34] Called to Florence by the Medici court in 1639, Rosa found himself in the footsteps of Filippo di Liagno, called Filippo Napoletano (1589-1629), whose four years, 1617-21, in Florence had left an indelible imprint. Rosa would have already seen Napoletano’s landscapes in Rome, but nothing like the bizarre mixture of natural, zoological and magical imagery that Filippo had unveiled and developed at the secular court of Cosimo II de’ Medici. Marco Chiarini was the first to recognize the fundamental influence of Filippo’s Officina dell’archimista (1619, Palazzo Pitti) on Rosa’s scenes of frantic witches and sorcerers. Cf. M. Chiarini, “Appunti su Filippo Napoletano e la pittura nordica”, in ‘Ricerche sul ‘600 napoletano’, 1996, fig. 17, pp. 60-61; M. Chiarini, Filippo Napoletano Vita e opere, Centro Di, Firenze, 2007, cat. n. 44, p. 274. In his Florentine years, Salvator Rosa based his tenebrist paintings of witchcraft (stregonerie) on a wide range of influences from Filippo Napoletano, principally, but also Leonaert Bramer, the Dutch Bamboccianti, and David Teniers II, which he assimilated into a brazenly repellent and yet semi-comical style that was unique and never emulated.

[35] Salvator Rosa (1615-73). Temptations of St Antony, 1643, c. 125 × 93 cm, Palazzo Pitti, inv. 1912 n. 297. According to J. Scott, 1995, p. 10, This painting was the first of Rosa’s paintings of stregonerie in Florence.

[36] F. Baldinucci, Notizie dei professori del disegno da Cimabue in qua […], ed. Firenze 1830, p. 18.

[37] A few years later Rosa will draw upon the same etchings for his insertion of animal skulls in his Democritus of 1650, and of course the wolf and horse skulls in in the present painting. These stylistic and iconographical connections between the Grotto and the Democritus of the same years are too numerous to address in this space. The scholarship on the Democritus dates back to Richard Wallace in 1968. Here are but two excellent recent studies: Eva de la Fuente Pedersen, “Salvator Rosa’s Democritus and Diogenes in Copenhagen,” PerspectiveJournal.dk, online , March 2017. Rosa was also influenced by G.B. Castiglione’s earlier etching of Democritus.

[38] Filippo Napoletano, Aeneus and the Sibyl in Hades, private collection, Cf.M. Chiarini, “Appunti su Filippo Napoletano e la pittura nordica”, in ‘Ricerche sul ‘600 napoletano’, 1996, fig. 12 a p. 50, ,pp. 60, 62 n. 7: Filippo Napoletano, Aeneus and the Sibjl in Hades, Galleria Doria Pamphilj, Rome, Cf Ibid., fig. 3 a p. 42.

[39] Caravaggio’s innovative iconography portrays St Matthew’s arms as a holy ladder between the baptismal waters of salvation, seen below, and the eternal life of the Cross and the angel on high who proffers the martyr’s Cross. Matthew’s gesture of cupping the water is echoed by Rosa’s Anthony, without expressing the same symbolism.

[40] The Medici and their courtiers were avid collectors of Caravaggio and the Caravaggists. An excellent exhibition was devoted to this theme. See G. Papi, a cura di, Caravaggio e caravaggeschi a Firenze, Galleria Palatina e gli Uffizi, Firenze, 2010.

[41] Court dwarfs in similar attire appear in both Venetian and Florentine Renaissance paintings: Vittorio Carpaccio, Arrival of the English Ambassadors, from the St. Ursula Cycle, 1498, Accademia, Venezia; Giuliano Bugiardini (Florence 1496-1555), Scenes from the Story of Tobias, c. 1500, Staatliche Museen, Berlin. Cf. N. Lubrich, “The Wandering Hat: Iterations of the Medieval Jewish Pointed Cap”, Jewish History , December 2015, p. 239, Fig. 37).

[42] M. Chiarini, Filippo Napoletano Vita e opere, Centro Di, Firenze, 2007, cat. n. 44, p. 274. See note 34 supra.

[43] Rosa’s tenebrist backgrounds and use of tiny white reflections to delineate black armor can perhaps be traced to the influence of Leonard Bramer (Delft 1596-1674), who was active in Rome from from 1616 – 1617, nick-named Leonardo delle Notti for his dark background painted on slate. Compare Bramer’s Scene with soldiers. 1626 ,Monogramed and dated at lower left: LvB 1626, Bredius Museum, The Hague. Bramer specialized in moralistic allegories of vanity, etc., with depictions of demons and skeletons influenced by Filippo Napoletano.

[44] The consultation of large, open books is one of the attributes of a magus.

[45] Recently Eva de la Fuente Pedersen, 2017, has suggested that Vasari’s high praise of Piero’s nocturnal paintings underscore the Renaissance influences on Rosa’s paintings: “Above every other consideration of ingenuity and art is that he had painted the night … [when] Constantine, was asleep in a pavilion watched by a waiter and by some armed men obscured by the darkness of the night. With the same light Piero illuminates the pavilion, the armed men and all the surroundings, with great discretion, and thus demonstrates with this darkness how important it is to imitate true things, and to make them his own. Having done this very well, he has given the moderns reason to follow him and reach that highest level where such works are seen today. (Vita di Pietro della Francesca, 1550)

[46] J.P. Davidson and Bob Canino, “Wolves, Witches, and Werewolves: Lycanthropy and Witchcraft from 1423 to 1700,” Journal of the Fantastic in the Arts. 2 (1990): 47-48, note the ancient legends of associations between witches and wolfs, noting also that Ultricus Molitoris, De lamiis et phitonicis mulierbus, 1489, believed that witches could transmute themselves into wolves and dogs.

[47] Pieter van der Heyden (Flemish, c. 1530–after 1572) After Pieter Bruegel the Elder (Netherlandish (active Antwerp and Brussels), c. 1525–1569) Published by Hieronymus Cock (Netherlandish, c. 1510–1570)

[48] This hypothesis merited consideration, and indeed has gained in credence. See Appendix I, for an 1898 description of the Sasso as resembling ‘dogs’.

[49] Philipp Peter Roos detto Rosa da Tivoli, Grotta marina con pastore a cavallo, 97 x 81 cm, Hermitage Museum, inv. GE- 6474, and Landscape with a Waterfall, 97 x 82 cm, Hermitage Museum, GE-1336

[50] Another Roos Waterfall, 96.5 x 66.7 cm (possibly cropped at right) in the style of Rosa is at Stourhead, National Trust UK.

[51] Philipp Peter Roos. Cavalier venant se désaltérer à la cascade (Horseman in Front of a Waterfall), 120 x 96cm, Artcurial, Paris, Vente Tableaux anciens, 08 November 2011, lot 39. «Notre tableau est à mettre en rapport avec la composition de l’artiste conservée à Saint Petersbourg au musée de l’Ermitage (toile, 97 x 81 cm)».

[52] One of Magnasco’s best known paintings, exhibited in the Pittura Italiana del Seicento e del Settecento alla Mostra di Palazzo Pitti in 1922, and in the collections of Conte Alessandro Contini-Bonacossi in Rome and, most recently, Otto Naumann in New York. The painting was recently seen at Christie’s, New York, lot 100. 9 JUN 2010 Old Masters & 19th Century Art Including Select Works From the Salander-O’Reilly Galleries. A copy of the present offered at Sotheby’s, Olympia, London, 4 July 2006.

[53] The mistaken belief that Roberto Longhi ascribed the shepherds in this painting to Rosa da Tivoli is a misreading of that began with a caption in the 1980 edition of Longhi’s comments in 1922. Longhi wrote that the sheep and some of the figures were painted by ‘a Roman painter influenced by Rosa da Tivoli”. See R. Longhi, Scritti giovanili, 1912-1922, Florence, ed. 1980, p. 505, fig. 247,

[54] For the provenance and changing attributions of these two paintings, see C. Geddo, “La galleria firmiana: il filone dei lombardi”, in Le Raccolte di Minerva. Le collezioni artistiche e librarie del conte Carlo Firmian Atti del Convegno, Trento-Rovereto, 2013, Rovereto 2015, pp. 57 – 99. Axel Vécsey, “The Reception of Seventeenth- and Eighteenth-Century Italian Painting in Hungary: Taste and Collecting”, in Caravaggio to Canaletto. The Glory of Italian Baroque and Rococo Painting, p. 133, Note 169: “Recently, a Rocky Landscape (inv. 57.17), previously attributed to Sebastiano Ricci, was also reattributed to Magnasco by L. Muti, and D. De Sarno Prignano, Alessandro Magnasco. Faenza, 1994. p. 206, no. 42.

[55] Formerly in the Mainoni d’Intigliano collection in Roma. See E. Castelli, Simboli e immagini; studi di filosofia dell’arte sacra, Rome, 1966, Tav. VIII. Online: https://archive.org/details/simbolieimmagini0000cast/page/n39/mode/2up

[56] G.A.Cesareo, Poesie e Lettere edite e inedite di Salvator Rosa, pubblicate criticamente e precedute dalla vita dell’autore rifatta su nuovi documenti, vol. I, Tipografia della Regia Università, Napoli, 1892. Link online: https://books.google.com/books?id=oK4_AAAAMAAJ&newbks=1&newbks_redir=0&printsec=frontcover&dq=Poesie+e+Lettere+edite+Salvator+Rosa&hl=it#v=onepage&q=sasso&f=false

[57] Ibid., p. 72, « Il sasso per sé medesimo richiamava al pensiero i cani; tale fu a punto l’intenzione del maligno pittore, che qualche mese dopo se ne vantò nella satira dell’Invidia.

[58] De Dominici, Vol. III, 1742, p. 242. also said no painter ever painting caverns fra dirupi o grottos con tal naturaleza. JTS: SR gave far more expression to his cliffs and stones than to his small figures, for which Leandro Ozzola dubbed ‘maquettes’., “since it would be vain to search in them for psychological significance. L Ozzola Works of SR in Engalnad BurlM Dec. 1909, p. 150.

[59] Salvator Rosa, La Strega, [The Witch], lines 66-69. For further information on La Strega, see H.L.P. Segrave, 2022, p. 311.

[60] In Virgil’s Aeneid, (vi. 297), Tartarus is a poetic metonymy for the Underworld or Hades.

ITALIAN TRANSLATION

Prologo: Il dipinto perduto di Salvator Rosa, Il Sasso

A metà del XVII secolo, quando la maggior parte dei pittori romani gareggiava per rappresentare gli angeli della maestà celeste, Salvator Rosa esplorava con insistenza le profondità più oscure della Natura. Nonostante le loro differenze, la maggior parte degli artisti attivi a Roma si consideravano discendenti della cultura classica. Salvator Rosa, per non essere da meno, studiò attentamente la storia e la mitologia greca e romana alla ricerca di soggetti mai dipinti prima. È la misura del genio di Rosa l’essere riuscito a trasformare testi arcani e scogliere e rocce primordiali in composizioni avvincenti. Lo scopo del presente articolo è quello di dimostrare, sulla base di nuove ricerche, l’autenticità e il significato artistico di un dipinto di Rosa, Soldati in una grotta (o brevemente, Grotta).

Quando Salvator Rosa tornò a Roma nel febbraio 1649 dopo quasi nove anni alla corte dei Medici a Firenze, [2] confidò ai suoi amici che intendeva affermarsi come pittore-filosofo la cui inventiva avrebbe stupito i suoi colleghi e mecenati. Ben presto poté riferirlo

“Poiché Roma ha imparato quanto siano estremamente stravaganti le mie innovazioni, ora devo persistere il più possibile.”[3]

Due anni dopo, in una lettera del 27 marzo 1653 all’amico poeta Giovan Battista Ricciardi, Rosa lamentava le critiche che gli erano state rivolte dopo l’esposizione di un suo dipinto al Pantheon di Roma.[4] Rosa si vendicò dei suoi detrattori inviando alla mostra del Pantheon, nel giorno della festa di San Giuseppe, il 19 marzo 1653, un dipinto scandalosamente anticonvenzionale. Descrisse questa ritorsione in poche righe nella sua satira Invidia, che scrisse scrivere in questo momento. Affermava che il soggetto del dipinto era semplicemente un “sasso [enorme roccia], nient’altro”, la cui audacia avrebbe lasciato i suoi critici “a far schioccare i denti di gelosia”, a dispetto del decoro accademico.[5] Purtroppo sappiamo poco altro di questo affascinante Sasso, la cui successiva collocazione è sconosciuta agli studiosi moderni. Nuove ricerche hanno però scoperto che il dipinto venne citato due volte a Napoli nel Settecento e nell’Ottocento. (Vedi Appendice II infra). Fu solo nel 1991 che Luigi Salerno riprese lo studio del Sasso con la proposta di identificare il quadro perduto di Rosa con un paesaggio passato all’asta da Christie’s, Londra.[6] Come prova della sua teoria, Salerno lo descrisse

«Il vero protagonista della composizione è un grande masso di pietra presso il quale due piccoli eremiti sembrano essere stati aggiunti solo per dare un minimo di accettabilità al soggetto».[7]

Alla fine, tuttavia, c’erano poche differenze tra il dipinto londinese e altre scene montane simili di Rosa. Nel 1995, Jonathan Scott si oppose alla proposta di Salerno e offrì la sua ipotesi sul perduto Sasso:

“Il quadro, che ora non può essere identificato, doveva essere un paesaggio che comprendeva una romantica rupe, uno di quei dipinti belli e popolari che i suoi critici avrebbero trovato difficile criticare.”[8]

Ulteriori indagini sul Sasso sono state scarse a partire dagli anni ’90 con la parziale eccezione di Alexandra Carol Hoare, che ha dimostrato l’uso frequente della parola “sasso” da parte di Rosa nella sua poesia.[9] La dott.sa Hoare sperava che un giorno il dipinto perduto venisse recuperato.

Salvator Rosa e la costa rocciosa di Napoli

Formazioni rocciose, grotte e montagne hanno affascinato per tutta la vita Salvator Rosa, alla periferia di Napoli, in piena vista di un vulcano attivo, il Vesuvio, e a pochi passi dalle coste rocciose presumibilmente infestate da sirene malvagie. Settant’anni dopo la morte di Rosa, il suo biografo napoletano, Bernardo De Dominici, citava una leggenda locale secondo cui Rosa e un altro giovane pittore, Marzio Masturzo, avevano sviluppato le loro abilità prendendo il mare su una piccola barca per

“disegnare i panorami della bellissima costa di Posillipo nonché delle coste verso Pozzuoli. Disegnarono quasi tante coste quante ne aveva prodotte la Natura».[10]

Quelle meravigliose coste sono state modellate nel corso di milioni di anni dalla dissoluzione del morbido substrato roccioso calcareo da parte delle acque correnti mescolate con l’acido carbonico lisciviato dal suolo. Le fessure furono gradualmente allargate fino a formare grotte corrose in forme fantastiche. Un paio di piccole scene costiere nel Palazzo Corsini a Roma sono le prime prove della passione di Rosa per le composizioni in cui le figure in primo piano sono oscurate dalle massicce pareti rocciose che sembrano guardarle in cagnesco.[11] [Fig. 2 e Fig. 3]

Come in quasi tutti i suoi dipinti costieri della sua carriera, le scogliere rocciose sono forate dall’oscuro ingresso di una grotta.[12] Da tempo immemorabile alcune grotte lungo le coste napoletane da Pozzuoli a Salerno erano venerate come leggendarie dimore di sibille, sirene e altri mostri marini conosciuti dalla mitologia greca e romana.[13] Nella sua Naturalis Historia del 77 d.C., Plinio il Vecchio menziona molte grotte, tra cui la Grotta del Cane nei Campi Flegrei, la Grotta di Cuma sulle colline vulcaniche vicino a Pozzuoli e quindi vicino al Vesuvio, nonché la Grotta Azzurra a Capri. Virgilio descrive nell’Eneide (Libro VI.64) come Enea, giunto a Cuma, andò subito a cercare la profetessa nel suo “antro di mirabile grandezza, terribile rifugio della sibilla” per ottenere la sua guida nella discesa nell’Ade. Venne avvertito:

«Facile è la discesa all’Averno, notte e giorno è aperta la porta oscura dell’Ade, ma ritornare sui propri passi e ritornare nelle arie superiori, questo è il compito, questa è la fatica».[14]

Secoli dopo, Dante, ispirato da Virgilio, adattò il mondo sotterraneo greco-romano alla teologia cristiana. Agli albori del Rinascimento, Leonardo da Vinci confessò la sua fascinazione per le grotte:

“E dopo essere rimasto per qualche tempo all’ingresso, sorsero in me due sentimenti contrari, timore e desiderio: timore della minacciosa grotta oscura e desiderio di vedere se vi fosse qualche cosa meravigliosa al suo interno.”

Al culmine del Rinascimento, Michelangelo fece intronizzare la Sibilla Cumana come una profetessa che leggeva dai libri sul soffitto della Cappella Sistina. Nei suoi ultimi anni romani, Rosa dipinse un grande paesaggio del dio Apollo con la Sibilla Cumana (Collezione Wallace, Londra). Negli anni Quaranta del Seicento, quando Rosa era a Firenze, La Discesa di Virgilio e Dante agli Inferi era diventata un soggetto popolare nell’arte dove i due poeti erano raffigurati all’ingresso della Grotta della Sibilla (Cuma) [Fig. 4].[15] Viaggiatori ed esploratori potevano trovare la strada per le grotte vicino a Napoli con un atlante geografico straordinariamente accurato di Leandro Alberti, Descrittione di tutta Italia, pubblicato per la prima volta nel 1568, con molte ristampe. Già dalla fine del Settecento le grotte del litorale napoletano e salernitano attiravano naturalisti, speleologi e non pochi paesaggisti influenzati da Salvator Rosa. Tra questi ultimi, forse il più eminente fu Joseph Wright di Derby, artista britannico che venne in Italia nel 1774 e realizzò diversi buoni dipinti di grotte con briganti in aperto omaggio a Salvator Rosa (Fig. 5).[16]

Come notò acutamente il De Dominici, la creazione delle imponenti scogliere e delle grotte predilette da Rosa furono da tutti riconosciute come opere d’arte realizzate dalla Natura. La convinzione filosofica in un’eterna competizione tra Arte e Natura ha radici antiche in Plinio il Vecchio e Ovidio (Metamorfosi). La “magia naturale”, magia naturalis, era un ramo rispettato della filosofia naturale, simile alla poco raccomandabile negromanzia ma distinta per i suoi metodi di indagine illuminati. L’umanista fiorentino per eccellenza, Pico della Mirandola osò dire:

“Non c’è forza latente in cielo o in terra che il mago non possa liberare con incentivi adeguati.”

La filosofia di Pico conferiva potere agli artisti in modi che suscitarono i sospetti della Chiesa romana, ad esempio:

“Ciò che il mago umano produce mediante l’arte, la natura lo produce naturalmente producendo l’uomo.”[17]

In breve, inserendo l’arte magica nella Natura, l’uomo può liberare forze più grandi delle sue. Edgar Wind ha sottolineato che Leonardo da Vinci mantenne viva questa filosofia magica nei suoi taccuini del Cinquecento: “La natura è piena di cause latenti che non si sono mai liberate” [18] Più vicino al tempo e al luogo di Rosa era l’universalmente noto il Magiae Naturalis, Napoli, 1558, del filosofo napoletano Giovan Battista Della Porta (1535–1615). [19] Questa breve rassegna degli antecedenti filosofici viene offerta come introduzione alle possibili interpretazioni delle formazioni rocciose zoomorfe della Grotta di Rosa [20].

Nel maggio del 2023, un grande dipinto, 94 x 78 cm, rappresentante un’oscura grotta sotterranea è passato per il mercato dell’arte a Firenze (Fig. 1).[21] Era la terza volta che i Soldati in una grotta di Salvator Rosa venivano esposti in un’asta pubblica dopo la riscoperta da parte di Nicola Spinosa in una collezione privata a Napoli nel 2008. La prima delle due precedenti occasioni per studiare il Grotto fu il suo inserimento in una grande mostra, Salvator Rosa tra mito e magia, curata da Spinosa per il Museo di Capodimonte.[22] La voce in catalogo di Brigitte Daprà, specialista in dipinti napoletani, è stata un’analisi convincente di questa intrigante aggiunta all’opera di Rosa, firmata in modo visibile con il monogramma “SR” dell’artista. Sono stati registrati alcuni disaccordi sull’attribuzione come spesso accade con i dipinti di antichi maestri, anche se meno spesso quando sono firmati.[23] Le osservazioni di Daprà sulla Grotta sono state tradotte in tedesco per il catalogo di Caravaggios Erben – Barock in Neapel, 2016-2017, importante esposizione antologica sul tema di Caravaggio e dei suoi seguaci napoletani.[24] L’attribuzione a Rosa sembra non essere stata discussa alla mostra in Germania.

La Grotta si distingue nell’opera di Rosa come un raro esempio di interno cavernoso visto dal pavimento della grotta, guardando verso l’alto verso l’ingresso con una piccola macchia di cielo azzurro.[25] Vale la pena notare che Rosa utilizzò punti di vista simili nei suoi dipinti di archi naturali in cui le piccole figure in primo piano sembrano sminuite dalle rocce colossali sopra di loro.[26] Altra particolarità della Grotta è l’audacia dell’artista nell’avvolgere l’interno in un’oscurità opaca, che appiattisce otticamente le tre piccole figure, privandole dell’effetto modellante della luce diurna, e rendendole quasi invisibili. Con un’originalità mozzafiato, Rosa ha combinato queste tecniche per rendere realistica la scena fantastica. La recente esposizione della Grotta in Firenze ha fornito l’occasione per riesaminare il dipinto con l’intento di rivedere le attribuzioni e i disaccordi. Il 23 maggio 2023, Soldati in una grotta di Rosa, come era intitolato, è stato venduto ad un’asta di dipinti antichi presso Pandolfini Casa d’Aste a Firenze.[27] La scheda del catalogo di vendita è stata redatta da Ludovica Trezzani, esperta di pittura italiana del Seicento, che ha sostenuto l’attribuzione e ha citato l’ipotesi di Brigitte Daprà di un possibile collegamento tra questa Grotta e il perduto Sasso:

“Non è certo un caso che nel 1653 Salvator Rosa scelse un paesaggio rupestre per sfidare il mondo accademico esponendo a Roma un dipinto intitolato Il Sasso: un’occasione per dimostrare la sua superiorità tecnica, nonché il suo disprezzo per la stabile gerarchia tra generi pittorici cominciando dal soggetto».[28]

Incuriosito da questa rara opportunità di studiare dal vivo la Grotta di Rosa, ho telefonato a Ludovica Trezzani e ho chiesto un appuntamento per visionare insieme il dipinto – sempre un esercizio utile – alla anteprima della esposizione di Firenze. Sabato mattina, 20 maggio, ho incontrato la dott.ssa Trezzani davanti al dipinto che, fortunatamente, era ben illuminato dalla luce del giorno. Abbiamo riscontrato di essere entrambi d’accordo con l’attribuzione a Rosa come opera databile dopo il suo definitivo ritorno a Roma da Firenze.[29] Abbiamo anche condiviso l’ interpretazione del senso della composizione, che comprende due mostruose masse di pietra calcarea che emergono come fantasmi dalle profondità nere come la pece della grotta. Sembrava sorprendente che nessuno avesse notato prima che la più grande di queste terrificanti vette assomiglia a un lupo gigante che si lancia verso il fondo della caverna dove due uomini oscuri si sono rifugiati all’interno di un masso scolpito. Brigitte Daprà aveva alluso a queste forme inquietanti nel suo saggio in italiano e tedesco:

“Rosa presenta un repertorio quasi inesauribile di forme rocciose… che, poiché sono state ammorbidite dagli elementi [naturali], hanno assunto forme antropomorfe o zoomorfe.”[30]