di John T. SPIKE

13 December is the Feast Day of Saint Lucy

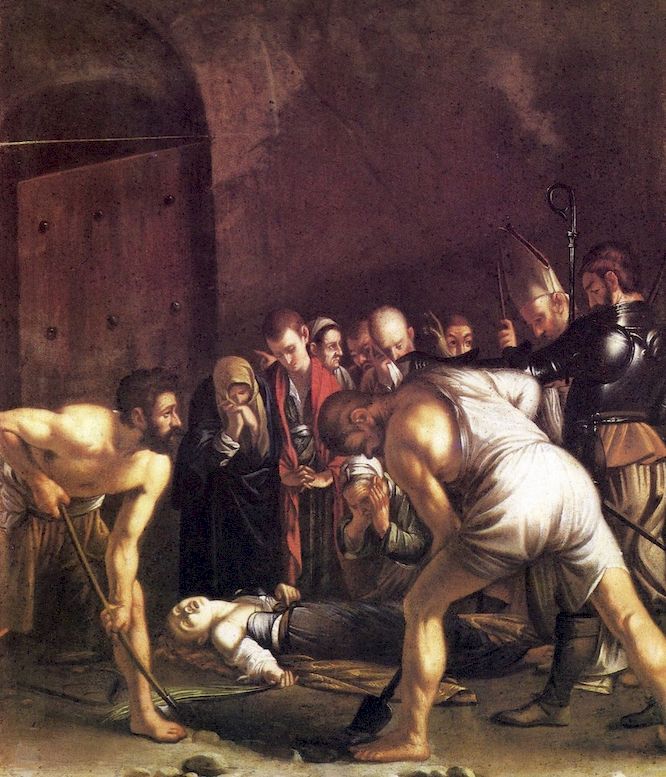

In October 1608, Caravaggio was in Siracusa, Sicily, after his escape from prison in Malta. At that time, a new altarpiece was needed for the church of Santa Lucia, patron saint of the city, and of vision. The church was built above the catacombs where the maiden martyr was laid after her death during the persecution of Diocletian, ca. 304. [1]

Mario Minniti, his studio mate from early Roman days, now presided over a thriving studio in Syracuse.[2] A later biographer confirmed that Minniti welcomed Caravaggio’s arrival in the ancient Greek colony and introduced him to the right people.[3]

Caravaggio’s Burial of Saint Lucy has come down to us in a seriously damaged state.

The two massive gravediggers bend over a dark hole that disappeared from the canvas long ago, worn away by heat and moisture. The maiden’s lifeless hand once grasped a martyr’s palm. In the arched alcove at left a wooden gate, slightly ajar, is now all but lost to abrasion.[4] Nevertheless, Caravaggio’s masterpiece, like a noble ruin, still preserves its aura of greatness.

A little throng of Christians keeps sorrowful watch over the crumpled corpse of their faithful sister Lucy. An immense void rises above them like the valley of the shadow of death. In the near foreground, the two diggers set to work concealing the evidence of her murder. Their mirror-image stances bracket the martyred Lucy, like a mandorla formed by human parentheses. Lucy’s emulation of Christ’s sacrifice is evoked by a startlingly original, and mystical, iconographical invention by Caravaggio: the two mourners standing above her recumbent form have assumed the identities of Mary and the apostle John at the foot of the Cross.[5]

One of the diggers pauses to look up. His gaze leads us across the picture to the right side where two figures of authority are issuing their contradictory commands. The Roman consul, wearing an armor breastplate, directs the diggers to their work. Behind his shadowy figure, a descending ray of light picks out a bishop’s white mitre, face, and hands. This early Christian prelate is solemnly blessing the little martyr.

These details can be seen more clearly in a small painting on copper (Fig. 2) that appears to date from the 17th century.

Saint Lucy’s chapter in The Golden Legend opens with words that would mean everything to an artist who held light sacred. Lucy means light. Light has beauty in its appearance; for by its nature all grace is in it, as Ambrose writes. It has also an unblemished effulgence; for it pours its beams on unclean places and yet remains clean… Again, Lucy means lucis via, the way of light.[6]

The light filtering through the penumbra of the Burial of Saint Lucy carries the same message as the beam of light in the painting that most resembles this one, the Calling of Saint Matthew. It is the light of grace.

Caravaggio invariably lit his figures from the left side except in four paintings only: the Burial of Saint Lucy, the Calling of Saint Matthew, and both the first and second Conversion of Saint Paul for the Cerasi Chapel. The theme of spiritual conversion is what these pictures have in common. The lateral positions of the paintings in the Contarelli and Cerasi chapels probably explains why Caravaggio organized their compositions so that the heavenly light descends from the right side. The Burial of Saint Lucy adopts this unusual scheme although it was destined for the high altar in the center of the nave, which suggests that Caravaggio had the Calling in his mind when he painted it.

In the Burial it is a gravedigger, a professional laborer in the vineyards of death, who lifts his head to discover that his orders have been eternally countermanded. The providential light of benediction shines on his face. The grace that illumined the stony hearts of Matthew and Paul now penetrates the darkest hour of martyrdom. Framed in an archway with a strait gate, the Roman’s minion must henceforth choose the way of light.

Meanwhile his heedless mate sinks ever deeper in the earthen grave. The same motif of spiritual sightlessness was used by Caravaggio in his Crucifixion of St Peter in the Cerasi Chapel (Fig. 3).

Santa Lucia brought candles to the Christians hidden in the Catacombs, a bringing of light appropriate for a feast day in Advent.

John T. SPIKE, N. Y., 13 december 2019

NOTE

[1] The relic of Saint Lucy was carried off to Venice in 1204 and perhaps the central representation of the saint’s body was intended to compensate for the loss.

[2] Caravaggio and Minniti are generally believed to have lived together in the Palazzo Madama, Rome, until at least 1600. Minniti is documented in Sicily after 1606. See Macioce, “Mario Minniti”, 1998, pp. 337-338.

[3] Susinno 1724 [ed. 1960, p. 110].

[4] The original appearance of the altarpiece have been reconstructed with the aid of an early copy (by Mario Minniti?) illustrated by Marini 1987, p. 292.

[5] The young man, often described as a “deacon”, wears John’s characteristic garments of red and green. Hibbard 1983, p. 239; Marini 1989, p. 535. The prominence afforded to this figure must have been inspired by the strength of his cult in Syracuse and in respect of the Greek philosophical background to his Gospel.

[6] The Golden Legend c. 1280 [trans. ed. Ryan – Rippirger, 1969 p. 34]

TRADUZIONE ITALIANA