di Irving LAVIN

Institute for Advanced Study. Princeton, NJ

CARAVAGGIO, MAGISTER AND THE BEATLES

In the painting, following the line that separates light from darkness, anyone who knows how to “see,” knows where it points. It is no accident that Christ converts, instantaneously, the typically red-bearded Jewish tax collector with a stylish broach in his hat, pointing with his index finger bent half-shadowed inward toward his inner self: his gesture does not ask, “who me?,” it simply indicates that “I” am a new man. In fact, he is the only figure who faces the viewer directly with both legs exposed to begin his response to the call. Christ here, appropriately, inevitably, uses the same gesture God the Father had used to create Adam in the Sistine ceiling, as does Peter his follower and successor. In the Contarelli chapel the line separates light from darkness (even the windows are dark), as did God in Genesis, and illuminates Matthew at his mouth, whence he will write, in his native Hebrew tongue, the first gospel, which relates the genealogy of Salvation from Abraham to Jesus. Christ’s gesture is thus in both cases a gesture of creation, the creation of a New Man, whose language in this case serves to retrieve relapsed Jews who have wandered from the true faith, and thus fulfill at last, necessarily, the promise of the Old Law in the salvation of the New.

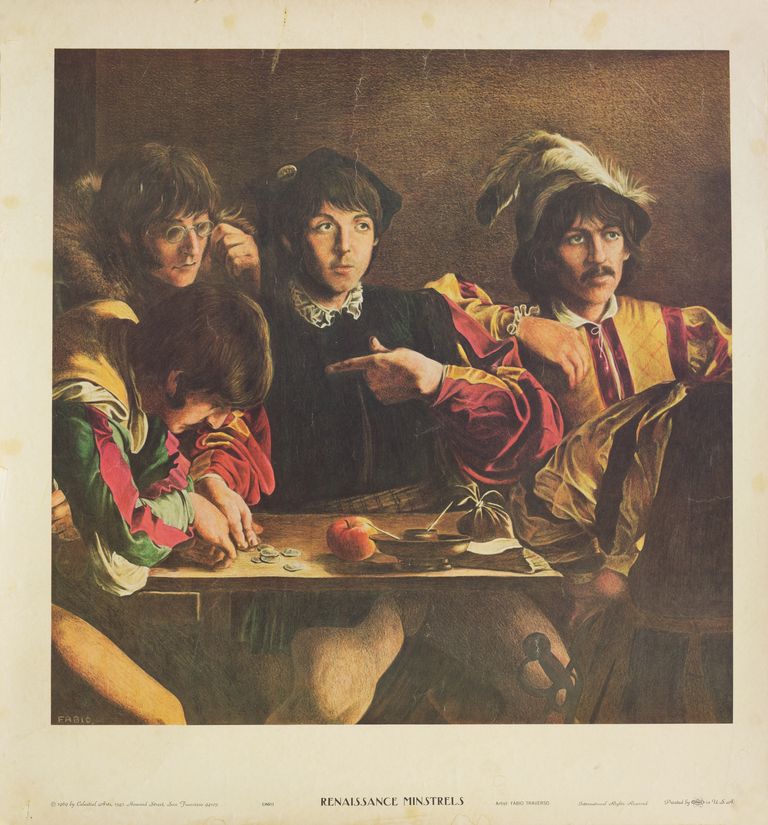

In a famous Beatles poster made in 1969, Paul McCartney is portrayed as Caravaggio’s Levi-become-Matthew in the center of the composition (a commercial Apple added). By no mistake, the poster’s creation coincided in the same year with the recording of Paul’s famous song Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. McCartney, who was a Liverpool born, baptized Catholic, Jesuit-schooled, surely knew that, following long tradition, when a pope dies the Camerlengo, in the presence of the other cardinals, taps him on the head with a silver hammer, three times to prove that he is dead. In the poster, even the 20th-century artist, Fabio Traverso, knows who is being called. The choice of scene, no doubt, had to do with the concomitance of the song, and Paul’s name with that of the current pope (Paul VI, 1963-1978).

*For information on the manifold religious lives of Paul McCartney and the Beatles see the website Beliefnet.

Italian Translation

Nel dipinto, seguendo la linea che separa la luce dall’oscurità, chiunque sappia “vedere” sa dove punta. Non è un caso che Cristo converta, istantaneamente, il tipico esattore delle tasse ebreo dalla barba rossa con una spilla elegante nel cappello, indicando con l’indice piegato a metà ombreggiato verso l’interno di sé: il suo gesto non chiede “chi io ?, indica semplicemente che “Io” sono un uomo nuovo. Infatti, è l’unica figura che affronta lo spettatore direttamente con entrambe le gambe esposte per iniziare la sua risposta alla chiamata.Cristo qui, appropriatamente, inevitabilmente, usa lo stesso gesto che Dio Padre ha usato per creare Adamo nel soffitto della Sistina, come fa Pietro il suo seguace e successore. Nella cappella Contarelli la linea separa la luce dalle tenebre (anche le finestre sono scure), come fece Dio in Genesi, e illumina Matteo alla sua bocca, da dove scriverà, nella sua lingua ebraica nativa, il primo vangelo, che mette in relazione la genealogia della Salvezza da Abramo a Gesù. Il gesto di Cristo è quindi in entrambi i casi un gesto di creazione, la creazione di un uomo nuovo, il cui linguaggio in questo caso serve a recuperare ebrei recidivi che hanno errato dalla vera fede, e quindi adempiere finalmente, necessariamente, alla promessa della Antica Legge nella salvezza della Nuova.

In un famoso poster dei Beatles realizzato nel 1969, Paul McCartney è ritratto come Levi-diventato-Matteo di Caravaggio al centro della composizione (con la Apple aggiunta per pubblicità commerciale). Per non sbagliare, la creazione del poster coincise in quello stesso anno con la registrazione della famosa canzone di Paul Maxwell’s Silver Hammer. McCartney, che era nato a Liverpool, battezzato cattolico, educato dai gesuiti, sicuramente sapeva che, seguendo una lunga tradizione, quando un papa muore il Camerlengo, in presenza degli altri cardinali, lo colpisce sulla testa con un martello d’argento, tre volte per dimostrare che è morto. Nel poster, anche l’artista del XX secolo, Fabio Traverso, sa chi viene chiamato. La scelta della scena, senza dubbio, ha avuto a che fare con la concomitanza della canzone, e il nome di Paolo con quello delpapa di allora Paolo VI (1963-1978).

Irving LAVIN Princeton New Jersey (USA) 1° ottobre 2018