di Clovis WITHFIELD

(original english text – italian translation)

The enigma of Caravaggio’s missing years, between 1592 in Milan and 1595/ 96 in Rome extends beyond the date when the barber’s boy saw him working at Lorenzo Carli’s during Lent of 1596, but also to his production in the months prior to his being brought to Palazzo Madama.

These two mysteries have solutions that are related, and stem from his prodigious creativity, which was unrelated to his apprenticeship in Milan. He does appear to have been absent from the records after 1 July 1592 (in Milan) to the winter of 1595/96, when he was seen in Rome . Given that his existence subsequently is always punctuated with troubles, with the law and otherwise, it would seem likely that this period had something to do the the professione d’armi that Bellori described, for he is unlikely not to have broken the peace for three and a half years. The long struggle to prevent the Turks from reaching Vienna started in 1593, and the Holy Roman Emperor mustered much support, in Italy from the Papacy, from Ferrara, Mantua and Tuscany, territories through which the artist must in any case have travelled. The experience of the brutality of war would perhaps account for the artist s abrasive attitude that many describe, but it was the prelude to the tremendous creativity that we know from the period when he produced the works centred around the group of paintings associated with Girolamo Vittrice.

The fact that he started with such modest means and patronage – the usual avenues of religious inventions and complex emblems were denied to a foreigner without a base in the city – has to be understood in order to comprehend his personal ambition, driven as we know not only from Van Mander’s reportage, as one of those who push themselves forward without shame ‘si spingono avanti franchi e senza vergogna’ and he emerged with great effort from poverty through a determined work effort ’è faticosamente uscito dalla povertà mediante il lavoro assiduo’. Unlike the Bolognese contingent who arrived in town after the turn of the century, Caravaggio came without any introductions or recommendations, and above all without funds ‘poco provisto di denari’ as Mancini tells us (Considerazioni, I, p. 224) .

No Cardinal Sfondrati, Farnese, Peretti, Aldobrandini or Mgr Agucchi. He had learnt how to grind pigments and to use colours in Milan (as Bellori had heard[1]) but that seems to have been the limit of his apprenticeship. And he got into trouble and killed a friend so he may well have joined the Foreign Legion, as it were, to get away. Instead of artistic experience, sightseeing as it were, in Venice (as Bellori surmised) and other centres on the way to the capital. There is no trace (so far) of his life between Milan in 1592 and Rome in 1596, and no obvious echo in his work of what he had seen on his travels. But he clearly had no time for the work of others, while we can recognise a pattern of existence that could perhaps be explained by recruitment to a foreign legion, as it were, accounting for his combative nature. Tuscany sent 3,400 troops to support the Imperial army against the Turks in 1593, in the Ottoman Thirteen Years War (1593-1604) that was the reason for the reason for Clement VIII’s establishment (1594) of the Holy League, to drive the Ottoman Empire out of Europe.

The body of work that Caravaggio had done before he was recruited by Cardinal Del Monte, in the summer of 1597, is really quite remarkable. Apart from the the teste di santi he did for Lorenzo Carli, there are the many versions of the Boy peeling Fruit, others of the Boy Bitten by a Lizard, the Boy with a Vase of Roses, a remarkable Carafe with Flowers that Cardinal Del Monte noticed and bought, the portrait of Maffeo Barberini, more ritratti for the same, the many pictures that he did for the Priore of the Hospital S. Maria della Consolatione (which he took with him to his native Sicily) but also the ‘molti quadri’ that Mancini says he did in a room at Palazzo Petrignani. Prospero Orsi, living nearby, had been working on site with the architect Ottaviano Mascarino, and it is clear that the arrangement to use the space was prompted by his introduction.

Since the Monsignor returned from Forli only in the spring of 1597, it might seem as though Caravaggio’s use of this room preceded Petrignani’s return, for it seems a very short time (for the amount of work accomplished) before he moved on to Palazzo Madama in midsummer of the same year. It is unclear from Mancini’s account whether this overlapped with the stay at Cesari’s house (just off the Via dei Giubbonari), but he was most productive. The paintings included the Flight into Egypt now in the Galleria Doria, the Mary Magdalene now in the same collection, the Fortune Teller in the Louvre, a St John the Evangelist that may have been the painting Mancini was so proud of owning. Also from this time the painting called Lo sdegno di Marte, known through the version (Chicago, Art Institute) Manfredi did of it dal naturale’ (in 1613) through Mancini’s good offices and for Agostino Chigi. There were others, perhaps the Giudizio di nostro Signore that was a painting of ten figures that Caravaggio had done in just five days. And others, there is evidence that the composition of the Shepherd Corydon the so-called St John the Baptist (Capitoline Galleries) dates from this period. At first, for ‘Monsù Insalata’ Pandolfo Pucci, his first housing in Rome, he did not do more than some copie di devotione, although he started the subject of the Boy peeling Fruit, and the Boy Bitten by a Lizard.

Mancini had heard that he then was taken up by Giuseppe Cesari, (for whom he painted the Fruttaiolo now at Villa Borghese, and the Borghese Bacchus, that may have been bought through the rivenditore Costantino Spada by San Luigi dei Francesi. This was where Del Monte bought the Cardsharps, and where Cesari bought the Bacchus. presumably while the artist had an opportunity to work in at the building site at Palazzo Petrignani. The few weeks implied by the Monsignor’ s return from Forli in the spring seem too short for the work that Caravaggio seems to have accomplished.

Celio’s account emphasises how destitute the artist ‘passando poveramente’ was when Prospero found him after looking for him for a whole day in Rome. The range of his production is missing the name of a client who might have inspired these works, for which the young painter would have found difficult to buy the materials without sponsorship. There is also the question of who was the patron for the dipinti privati like the Shepherd Corydon and the Amore vincitore, that appear to stem from a particular enthusiasm of a necessarily private nature. It does not seem as though they were intended for Girolamo, the nephew of the very old Pietro Vittrice, whose chapel in the Chiesa Nuova would be adorned with the Deposition, now in the Vatican, for he was only sottoguardarobbiere to Clement VIII, and it was unlikely that he would have commissioned the ambitious and risqué paintings the artist did at Palazzo Petrignani. Nor do we know much about Petrignani’s personal taste, and no pictures by Caravaggio are associated with him.

So far, no reflections of the painter s experience of war. Whether he spent his missing years between 1592 and 1596 fighting in foreign territory, as has been recently restated by Rossella Vodret, [2] an experience as a soldier would go some way to explain his access to the arms that he always bore and used, and later according to Susinno, slept beside. As he strode around Rome with his sword at his side ‘Faceva professione d’armi, mostrando di attendere ad ogn’altra cosa fuori che alla pittura’ he followed the profession of arms and looked as though his occupation had nothing to do with painting’ (Bellori, 1672, p. 208). In reality Mgr Fantino Petrignani, who gave Caravaggio la commodità di una stanza at this crucial period of his career, was involved in the managing the payroll of the soldiery of Avignon in 1574. Chosen to be President of Romagna, he returned to Rome from Forli in 1597 to take up his new position as Papal Commissario for the esercito pontificio during the Ottoman War[3].. This job he resigned soon after his return to the capital, and he then turned to the building of his palazzo, which he and his brother Settimio had bought from the Santacroce in 1591. Still with ambitions for a cardinal s hat (less probable since the death of his patron Gregorio XIII in 1585)

This could have been one of the reasons that Caravaggio turned to him for accommodation, as a veteran. Petrignani was well connected in Rome prelato molto noto nella corte e molto ricco, and had worked with the Papal Treasurer Benedetto Giustiniani just before the latter was raised to the purple in 1586, and knew many of the future clients of Caravaggio, and was a key figure in the business of the Church. As was the case with Mgr Pandolfo Pucci, the artist evidently did pictures (copie di devotione) for his patron, but was also allowed to produce paintings for others, and this seems to have been the case also at Palazzo Petrignani.

But his was a volatile personality, and whether or not the paintings done at Petrignani s were sold because of the bankruptcy of his estate, or because Caravaggio no longer had a supporting employer, the pictures were dispersed, at knockdown prices, like the eight scudi it is said was paid for the Flight into Egypt.. The artist was very difficult to get along with, and even his friend Mario Minniti found a bride in to get away from him. He was ‘molto incline a duellare e fare baruffe’ [4] and in his house in 1605 he had many weapons, including swords and daggers and knives[5].

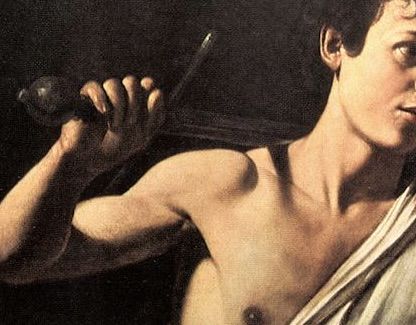

The examples he represented in his paintings are mostly of the proto-rapier family, the fighting sword of the sixteenth century soldier. The most detailed is the one in the Louvre Fortune Teller [6].

The zingara referred to by Bellori is one that the artist called in from the street, but he could have encountered Romapeople in Hungary, where they arrived with the Turks, and became the subject of proverbial prejudice. Naturally the swords in Caravaggio s paintings are accurately portrayed, with the same attention to detail as later with

Del Monte’s musical instruments. The Fortune Teller was evidently painted at Palazzo Petrignani, which is opposite Prospero Orsi’ s home, with the placet of the Monsignor who ‘gli dava la comodità di una stanza. Eventually it was presented to Louis XIV by Prince Camillo Pamphilj in 1665.

The weapon that Caravaggio owned himself was the example Capitano Pino drew 28 April 1605, when the painter was arrested for porto abusivo d’armi.[7] This was evidently also the basket-hilted sword beside St Paul in the Odescalchi Conversion of St Paul, that also looks like the sword confiscated from the artist.

A more lightweight example is the rapier in the hands of St Catherine (Madrid, Thyssen Collection),

another that which St Martin uses to divide his cloak in the Seven Acts of Mercy, another the German sword with the maker’s initials engraved in the blade that David has nused in the Borghese David and Goliath where the fuller (the flute running up the length of the blade, is inscribed with the initials of the maker.[8]

No need to invent symbolism in the letters, these are real weapons, like the musical instruments Caravaggio had as props, and reproduced with his trademark accuracy, dal naturale.

He carried the weapons, like a pistol in a holster, justifying it by his employment with Cardinal Del Monte. On 24 October 1605 he allegedly fell upon his sword, and was confined to bed by his friend Antonio Ruffetti.

What looks like a dagger [9] in the Cardsharps is instead a pair of compasses, just as lethal but perhaps allowed to be carried, whereas swords and daggers were not allowed. When arrested 3 May 1598 he was carrying a sword, but also two compasses, which the birro determined were offensive weapons.

In contrast the blade used by Judith in the Costa Judith and Holofernes is a falchion or Turkish scimitar, with a curved blade where the thickest part is located where it is most likely to strike the victim. It would have been associated with the Ottoman campaign and the attempt to drive the Turks out of Europe.

Mgr Fantino and his brother Settimio acquired in 1591 what was then the Palazzo Santacroce in Piazza S. Martinello, with all its debts . They appointed Ottaviano Mascarino as architect in 1592, but soon after Fantino was made Governor of Romagna, involving a move to Forli. The ambitious palazzo Petrignani was building was opposite the Trinità dei Pellegrini church in what was then Piazza S. Martinello [10] (Mascarino’s ground plan survives[11]). It extended from the Piazza S. Salvatore in Campo (now Piazza del Monte di Pietà), to Piazza S. Martinello. It included a gallery towards the piazza opposite SS Trinita with a room upholstered with red and yellow rasetto di Venezia. This at least gives an indication that the paintings intended for these spaces were canvases, rather than frescos, which Caravaggio was unable to do. It is tempting to think that the ambitious plans Mgr Petrignani had for developing his palazzo[12], in front of the SS Trinità dei Pellegrini, included decorations , we know only that there were to be many rooms apart from the planned galleria, that would have had pictures, drawn in the plan the architect made for the site (illustrated by M. Moretti, 2017, p. 126)., The project was in front of Prospero Orsi’s house and that of Maffeo Barberini, frequented by members of the Perugian Accademia degli Insensati.

Unfortunately Mgr. Fantino’s unexpected death in 1600 brought the building to a halt. The façade on Piazza S. Martinello still survives but the rest was left incomplete, the Petrignani heirs finally sold the unfinished site to the Monte di Pietà[13] in 1603. The facade of the building survives, with the main doorway, now the Comando Carabinieri ( Piazza Farnese), on the corner of Via dell’Arco del Monte which is the extension of the Via di Ponte Sisto. It was the culmination of Mgr Fantino’s career, but his death (April 10 1600) was an unmitigated disaster, followed by the loss of the Roman palazzo and that of the family at Amelia. The Roman building was sold in 1603 to the Sacro Monte, for the Monte di Pietà whose protettore was Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, whose niece Olimpia would buy the Vittrice paintings, painted at Palazzo Petrignani, for a nominal price from Caterina Vittrice in 1650. .

Caravaggio s use of the stanza, helped through the agency of Prospero Orsi, would have meant that he found space to work, and this seems to have given the artist a great opportunity to expand his work from the much smaller scale of the early ritratti, the studies dal naturale that he had such a talent for.The Flight into Egypt that Caravaggio had done at Palazzo Petrignani was sold for only eight scudi, and the knowledge of the trivial prices his works had made became legendary for the generation around Giulio Mancini, who most admired works like the Fortune Teller. It does seem possible that Petrignani was the phantom patron who inspired the amazing inventions of the year before Caravaggio moved into Palazzo Madama in the summer of 1597. He was a fast worker, Mancini wrote to his brother Deifebo in Siena of a painting that the artist had done, of the Giudizio di Nostro Signore with ten life-size figures, in five days, and he had also painted the ambitious Sdegno di Marte of Mars Chastising Cupid, that Mancini himself coveted, but which was bought by Cardinal Del Monte.

The remaining Vittrice pictures do not seem to have been accessible to connoisseurs in Rome, until they were inherited by Girolamo’s surviving daughter Caterina Vittrice, who had them§ from her brother Alessandro, Governor of Rome who died in 1650. Caterina sold them promptly to Olimpia Aldobrandini, who had married Prince Camillo Pamphilj in 1647, and after being hung briefly in the Casino del Belrespiro at Villa Pamphilj, they came to Palazzo Aldobrandini al Corso, where they remained (with the exception of the Fortune Teller, given to Louis XIV in 1665. But it seems possible that the palazzo in front of the Trinità dei Pellegrini was the original destination for this revolutionary group of paintings and reflect the taste of someone who had a discerning and tolerant eye. The inventions he came up with, like the Shepherd Corydon are so idiosyncratic that they seem to come from a quite different culture than that of the Catholic faith that was all around. I think that it was here that the artist painted the dipinti privati like the Shepherd Corydon, and the Amore Vincitore. The latter remained on the artist’s hands until it was bought by Benedetto / Vincenzo Giustiniani, after they started collecting ‘modern art’, in 1600.

Clovis WHITFIELD Umbria 3 Aprile 2022

Note

[1] In his notes to his copy of Baglione’s Vite, Biblioteca Corsiniana, ed. V. Mariani, Rome, 1935

[2] https://www.finestresullarte.info/debunking/caravaggio-ha-combattuto-come-soldato-in-ungheria

[3] See Moretti, 2017, p. 128.

[4] Karel van Mander, Het Schilderboek, Haarlem, 1604, translation by S. Macioce, Caravaggio, Documenti, 2003, p. 309

[5] R. Bassani & F. Bellini, ‘La casa, le “robbe”, Lo studio del Caravaggio aa Roma’ Prospettiva, luglio 1993, 71, p. 68-76

[6] See D. Macrae,Observations on the Sword in Caravaggio, in Burlington Magazine, v. 106, 1964, p. 412 / 416.

[7] repr. on cover of the exh. Catalogue, Una vita dal vero, Archivio di Stato,. Rome, 2011.

[8] Not an acronym for a a narrative that has been associated with H A S O S

[9] See this author’s Caravaggio’s Eye, London, 2011, p. 56

[10] The church (later S. Martino in Panarella) is no longer, although part of the face of the palazzo Ottaviano Mascarino was planning for Mgr Petrignani is still there, in Piazza SS Trinità dei Pellegrini .se)

[11] M. Moretti, I Petrignani di Amelia nella Roma di Caravaggio, in Roma al tempo di Caravaggio, Saggi, ed. R. Vodret, Milano 2012 p-.117-135. Mascarino’s ground plan for the palazzo Petrignani is illustrated, p. 126.

[12] The church (later S. Martino in Panarella) is no longer, although part of the face of the palazzo Ottaviano Mascarino was planning for Mgr Petrignani is still there, in Piazza SS Trinità dei Pellegrini with the elaborate entrance doorway opposite the facade of the church ; this is now the Comando Carabinieri (Piazza Farnese)

[13] M. Moretti, I Petrignani di Amelia nella Roma di Caravaggio, in Roma al tempo di Caravaggio, Saggi, ed. R. Vodret, 2017, p. 117-135

Traduzione italiana di Consuelo Lollobrigida

L’enigma degli anni tra il 1592 a Milano e l’arrivo a Roma di Caravaggio nel 1595/96, ancora sconosciuti, va ben oltre la data di quando il garzone del barbiere lo vede al lavoro per Lorenzo Carli durante la Quaresima del 1596, ma riguarda anche la produzione delle opere realizzate prima che venisse accolto a Palazzo Madama.

Questi misteri hanno una qualche relazione tra loro e hanno origine dalla sua prodigiosa creatività, che non è da far risalire al suo apprendistato milanese. Non ci sono tracce documentarie dopo il 1° luglio 1592 (a Milano) fino all’inverno 1595/96, quando fu visto a Roma. Dal momento che la sua esistenza è costellata di guai, con la giustizia ed altro, sembrerebbe verosimile che durante questo periodo oscuro possa aver avuto a che fare con la professione d’armi descritta da Bellori, dal momento che è improbabile che si sia mantenuto in pace per più di tre anni e mezzo. La lunga battaglia per assicurare che la Turchia non arrivasse fino sotto Vienna iniziò nel 1593, il Sacro Romano Impero raccolse molto sostegno in Italia, dalla Chiesa, da Ferrara, da Mantova e dalla Toscana, tutti territori che in qualche modo furono attraversati dall’artista. L’esperienza della brutalità della guerra potrebbe spiegare gli atteggiamenti aggressivi di Caravaggio la cui attitudine alla violenza è stata descritta da molti; ma un’esperienza del genere potrebbe era anche aver costituito il preludio alla fenomenale creatività che conosciamo nel periodo in cui produsse il gruppo di dipinti legati a Girolamo Vittrice

Il fatto che l’inizio della carriera sia caratterizzato da una scarsezza di mezzi e di mecenati, dato che i canali delle invenzioni religiose erano chiusi ad uno straniero senza una base in città, deve essere interpretata per comprendere la sua personale ambizione -come sappiamo non solo dalle parole di Van Mander- come uno che spinge avanti se stesso senza vergogna (‘si spingono avanti franchi e senza vergogna’) e che emerse con grande sforzo dalla povertà attraverso un costante e fermo sforzo lavorativo (è faticosamente uscito dalla povertà mediante il lavoro assiduo’). Diversamente dal contingente Bolognese che era arrivato in città al volgere del secolo, Caravaggio non ebbe né raccomandazione né introduzione alcuna e soprattutto era senza fondi – poco provisto di denari – come dice Mancini (Considerazioni, I, p. 224).

Per lui nessun cardinal Sfondrati, Farnese, Peretti, Aldobrandini o monsignor Agucchi. Aveva imparato a macinare e ad usare i colori a Milano (come aveva sentito Bellori[1]), ma questo sembra essere stato il massimo del suo apprendistato. Si era messo nei guai, uccise un amico, e quindi per scapparsene potrebbe essersi benissimo unito alla Legione Straniera. Tranne che un’esperienza artistica, non ebbe un’esperienza visiva a Venezia (come fa intendere Bellori) e in altri centri che incontrava nel suo viaggio verso la capitale. Non ci sono tracce (finora) della sua vita a Milano tra il 1592 e a Roma nel 1596, e nessuna chiara eco del suo lavoro circa quello che aveva visto nei suoi viaggi. In ogni modo, certamente non ebbe tempo di lavorare per altri, mentre possiamo riconoscere un modo di esistenza che si potrebbe spiegare con il reclutamento in una legione straniera, che si rifletteva nella sua natura combattiva. Nel 1593 la Toscana inviò un contingente di 3,400 uomini per sostenere l’esercito imperiale contro i Turchi nella Guerra Ottomana dei Tredici Anni (1593-1604), il che spiega la decisione di Clemente VIII di fondare una Lega Santa per cacciare l’Impero Ottomano fuori dall’Europa.

Monsignor Fantino Petrignani, già Maestro di casa di Gregorio XIII, aveva avuto molto da fare con la diplomazia papale, anche come Commissario pontificio per la lunga guerra contro i Turchi, per cui tornava a Roma nella primavera del 1597. Così era uno a cui un veterano di quella guerra avrebbe potuto verosimilmente rivolgersi. Questa nuova nomina fu presto disdetta, e Monsignor Fantino si dedicò in quegli anni (1597 – 1600) al progetto della costruzione del suo palazzo a Roma con l’architetto di famiglia Ottaviano Mascarino.

Il corpus di opere eseguite da Caravaggio prima di essere reclutato dal Cardinal Del Monte, nell’estate del 1597, è veramente degno di nota. A parte le teste di santi che fece per Lorenzo Carli, ci sono molte versioni del Mondafrutto, del Ragazzo morso dal ramarro, del Ragazzo con il Vaso di Rose, una notevole Caraffa con Fiori notata e comprata dal Cardinal Del Monte, il ritratto di Maffeo Barberini, e più ritratti per lo stesso, i molti dipinti che fece per il Priore dell’Ospedale di Santa Maria della Consolazione (che portò con lui nella sua nativa Sicilia) ma anche ‘molti quadri’ che Mancini dice che dipinse in una stanza di Palazzo Petrignani. Prospero Orsi, che viveva lì vicino, aveva lavorato con l’architetto Ottaviano Mascarino, ed è chiaro che fu lui a favorire l’introduzione di Caravaggio a Palazzo.

Dal momento che Monsignor (Petrignani, ndr) rientrò da Forlì soltanto nella primavera del 1597, potrebbe essere che Caravaggio abbia ottenuto l’uso della stanza anche prima del rientro di Petrignani, perché appare troppo limitato il tempo che ebbe a disposizione (vista la montagna di lavoro che eseguì) prima del suo trasferimento a Palazzo Madama avvenuto alla metà dell’estate dello stesso anno. Non è chiaro dal racconto di Mancini se questo periodo si sovrappose al suo soggiorno nella casa di Giuseppe Cesari (appena fuori Via dei Giubbonari), ma in ogni caso fu molto produttivo. I dipinti, incluso il Riposo dalla Fuga in Egitto della Galleria Doria Pamphilj, la Maddalena Penitente nella stessa collezione, la Buona Ventura del Louvre, il San Giovanni Evangelista, potrebbero essere i dipinti che Mancini era orgoglioso di possedere. Sempre a questo periodo risale Lo sdegno di Marte, conosciuto attraverso la versione che nel 1613 Manfredi fece ‘dal naturale’ (Chicago, Art Institute) grazie ai buoni uffici di Mancini e per Agostino Chigi. Ce ne erano altri, forse il Giudizio di nostro Signore, un dipinto di dieci figure che Caravaggio aveva fatto in appena cinque giorni. E altrettanto evidente che la composizione del ‘Coridone’, il cosiddetto San Giovanni Battista (Pinacoteca, Musei Capitolini) si dati a questo periodo. All’inizio, per ‘Monsù Insalata’, ossia monsignor Pandolfo Pucci, il suo primo locatario a Roma, non fece che delle copie di devotione, benché avesse iniziato il Mondafrutto e il Ragazzo morso da un ramarro. Mancini aveva sentito che era stato assunto da Giuseppe Cesari per il quale aveva dipinto il Ragazzo con canestra di frutta, ora alla Borghese, e il Bacco Borghese che forse acquisì attraverso il rivenditore Costantino Spada nei pressi di San Luigi dei Francesi. Questo fu anche il posto dove Del Monte acquistò i Giocatori di Carte e il Cesari il Bacco, presumibilmente mentre l’artista ebbe l’opportunità di lavorare in una stanza di Palazzo Petrignani.

Le poche settimane al servizio di Monsignor Petrignani, dopo il suo ritorno da Forlì, sembrano veramente poche per tutto questo lavoro. Il racconto di Celio enfatizza come fosse indigente l’artista – passando poveramente – quando Prospero lo trovò dopo averlo cercato per un intero giorno in giro per Roma. Anche se si perde il nome del cliente che potrebbe aver ispirato queste opere, è difficile pensare che non ci fosse qualcuno alle sue spalle che lo aiutasse, per esempio nell’acquisto del materiale per dipingere. Rimane sempre aperta la questione di chi fosse il committente dei dipinti privati come il Coridone e l’Amore vincitore, che sembrano scaturire da un entusiasmo particolare di un qualche privato collezionista. Tuttavia non sembra probabile che siano stati eseguiti per Girolamo, il nipote del vecchio Pietro Vittrice, la cui cappella nella Chiesa Nuova sarebbe stata decorata con la Deposizione, ora in Vaticano, perché questi era soltanto il sottoguardarobbiere di Clemente VIII, ed era poco probabile che potesse commissionare dei dipinti così ambiziosi e osé come quelli dipinti a Palazzo Petrignani. Tanto meno conosciamo i gusti personali di Petrignani, al quale nessuna opera di Caravaggio può essere associata.

Finora non è stata fatta nessuna riflessione sull’esperienza in guerra dell’artista.

Se avesse speso gli anni ancora ignoti, tra il 1592 e il 1596, combattendo in un territorio straniero, così come ha recentemente riaffermato Rossella Vodret[2], si potrebbe spiegare in qualche modo il suo accesso alle armi che aveva sempre con sé e che sapeva usare, e che più tardi avrebbe messo accanto al suo letto durante la notte, come sostiene Susinno. Da come andava in giro per le strade di Roma con la sua spada al fianco – ‘Faceva professione d’armi, mostrando di attendere ad ogn’altra cosa fuori che alla pittura’ – seguiva la professione delle armi e si guardava intorno come se la sua occupazione fosse tutt’altro che la pittura (Bellori, 1672, p. 208). In realtà Monsignor Fantino Petrignani, che diede a Caravaggio la commodità di una stanza in un momento cruciale della sua carriera, era coinvolto nella gestione delle buste paghe della soldatesca di Avignone nel 1574. Scelto per essere il Presidente della Romagna, tornò a Roma da Forlì nel 1597 per prendere la sua nuova posizione come Commissario Papale per l’esercito pontificio durante la Guerra Ottomana[3]. Ancora con l’ambizione del cappello cardinalizio (meno probabile dopo la morte del suo protettore Gregorio XIII nel 1585), rassegnò le dimissioni da questo lavoro non appena tornò nella capitale e prese a vivere nel palazzo che lui e suo fratello Settimio avevano comprato dai Santacroce nel 1591.

Questa potrebbe essere una delle ragioni per le quali il Caravaggio come veterano si rivolse a lui per una sistemazione. Petrignani era ben inserito a Roma – prelato molto noto nella corte e molto ricco – avendo lavorato con il tesoriere papale Benedetto Giustiniani poco prima che questi fosse eletto alla porpora nel 1586, e conosceva molti dei futuri clienti di Caravaggio, oltre ad essere una figura chiave negli affari della Chiesa. Come fu con Monsignor Pandolfo Pucci, l’artista evidentemente fece dei dipinti (copie di devotione) per il suo mecenate, ma aveva anche il permesso di produrre dipinti per altri, e questo potrebbe essere il caso anche di Palazzo Petrignani.

Ma la sua era una personalità volatile, e indipendentemente dal fatto che i dipinti realizzati a casa Petrignani fossero venduti a causa della bancarotta del suo patrimonio, o perché Caravaggio non aveva più un datore di lavoro di supporto, i dipinti andarono dispersi a prezzi stracciati, come nel caso degli otto scudi che si dice siano stati pagati per la Fuga in Egitto Doria.

L’artista era un personaggio a cui si stava difficilmente dietro; perfino il suo amico Mario Minniti si decise a sposarsi per allontanarsene. Era ‘molto incline a duellare e fare baruffe’ [4] e nella sua casa nel 1605 aveva molte armi, tra cui spade, pugnali e coltelli[5]. Gli esempi che rappresenta nei suoi dipinti appartengono alla famiglia degli spadini, la spada da combattimento dei soldati del XVI secolo. Quello più dettagliato si trova nella Buona Ventura del Louvre [6].

La zingara cui fa riferimento Bellori è quella che l’artista chiamò dalla strada, ma poteva anche essere una incontrata tra i Rom in Ungheria, dove erano arrivati con i Turchi e che divennero il soggetto di proverbiali pregiudizi.

Naturalmente le spade nei dipinti di Caravaggio sono ritratte con molta accuratezza, con la stessa attenzione al dettaglio che avrebbe usato più tardi nel rappresentare gli strumenti musicali per il cardinal Del Monte. La Buona Ventura fu evidentemente dipinta a Palazzo Petrignani, che si trovava proprio di fronte alla casa di Prospero Orsi, con il placet di Monsignore che ‘gli dava la comodità di una stanza. L’arma che possedeva Caravaggio era l’esemplare disegnato da Capitano Pino il 28 aprile 1605, quando il pittore fu arrestato per porto abusivo d’armi.[7]

Anche l’elsa a canestro accanto a san Paolo nella Conversione di san Paolo Odescalchi somiglia alla spada che gli era stata confiscata.

Un esempio più leggero è lo stocco nelle mani della Santa Caterina (Madrid, Thyssen Collection);

un’altra è quella che usa san Martino per dividere la cappa nelle Sette Opere della Misericordia; un’altra è la spada tedesca con le iniziali del forgiatore incise sulla lama che Davide ha usato nel Davide e Golia della Borghese, dove nella parte che corre su tutta la lunghezza della lama è inscritto con le iniziali del forgiatore[8].

Non c’è bisogno di inventare simbolismi nelle lettere, queste sono armi reali, come gli strumenti musicali che Caravaggio riproduce come strumenti di scena, e riproduce con l’accuratezza del suo stile, dal naturale. Portava armi, come una pistola nel fondino, di cui giustificava la detenzione con la scusa di lavorare per il Cardinal Del Monte. Il 24 ottobre 1605 cadde presumibilmente sopra la sua spada e fu costretto a letto nella casa del suo amico Antonio Ruffetti. Quello che sembra un pugnale nei Giocatori di carte[9] è invece un compasso, sicuramente letale ma forse non proibito, mentre spade e pugnali lo erano. Quando fu arrestato il 3 maggio 1598, portava una spada, ma anche due compassi, che il birro determinò essere delle armi offensive.

Per contrasto la lama usata da Giuditta nella Giuditta e Oloferne Costa è un falcione o una scimitarra turca, con la lama curva con la parte più spessa collocata proprio nel punto esatto per uccidere la vittima, e di qui si potrebbe pensare che Caravaggio fosse stato associato alla campagna militare ottomana, con il tentativo di espellere i turchi fuori dall’Europa. Monsignor Fantino e suo fratello Settimio avevano acquistato nel 1591 Palazzo Santacroce a Piazza S. Martinello, con tutti i suoi debiti. Chiamarono l’architetto Ottaviano Mascarino nel 1592, ma subito dopo Fantino fu nominato Governatore della Romagna, che significava un trasferimento a Forlì. L’ambizioso palazzo Petrignani era collocato di fronte alla chiesa dei Trinità dei Pellegrini in quella che era allora Piazza S. Martinello[10] (di Mascarino sopravvivono i disegni del piano terra[11]). Si estendeva da Piazza S. Salvatore in Campo (ora Piazza del Monte di Pietà) a Piazza S. Martinello. Includeva una galleria verso la piazza della Ss. Trinità con una stanza completamente decorata con rasetto di Venezia rosso e giallo. Questo almeno ci dà un’indicazione che le pitture che aveva ideato per questi spazi erano tele, anziché affreschi che Caravaggio non sarebbe stato in grado di eseguire.

Si può tentare di credere che Monsignor Petrignani avesse piani ambiziosi per sviluppare il suo palazzo[12], incluse le decorazioni, di cui sappiamo che dovevano svilupparsi in molte altre stanze oltre alla galleria già progettata (illustrato da M. Moretti, 2017, p. 126). Il palazzo si trovava di fronte alla casa di Prospero Orsi e di Maffeo Barberini, quest’ultima frequentata dai membri della perugina Accademia degli Insensati. La morte improvvisa di monsignor Fantino, nel 1600, sfortunatamente determinò un arresto nei lavori. Sopravvive ancora la facciata su piazza San Martinello ma il resto è stato lasciato incompleto, fino a che gli eredi della famiglia Petrignani vendettero il palazzo incompiuto al Monte di Pietà[13] nel 1603. Quello che rimane della facciata è il portale principale, ora Comando Carabinieri (Piazza Farnese), all’angolo con Via dell’ Arco del Monte che è un’estensione di Via di Ponte Sisto.

Fu quello il culmine della carriera di Monsignor Fantino, ma la sua morte il 10 aprile 1600 fu un disastro assoluto, seguita dalla perdita del palazzo di Roma e di quello della famiglia ad Amelia. L’edificio romano fu venduto nel 1603 al Sacro Monte; per il Monte di Pietà era protettore il Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini, la cui nipote Olimpia comprò nel 1650 per un prezzo nominale i dipinti da Caterina Vittrice.

L’uso della stanza da parte di Caravaggio, aiutato da Prospero Orsi, significava che aveva trovato uno spazio per lavorare e in questo modo aveva una grande opportunità per sviluppare il suo lavoro dalla scala più piccola dei primi ritratti, agli studi dal naturale per i quali aveva un talento innato. Il Riposo dalla fuga in Egitto che Caravaggio aveva dipinto a Palazzo Petrignani fu venduto, come si diceva, per soli otto scudi, ed erano diventati di comune conoscenza i prezzi bassi delle sue opere, ormai divenuti pezzi leggendari per la generazione di Giulio Mancini, che ammirava principalmente opere come la Buona Ventura. Sembra possibile che Petrignani possa essere stato il committente fantasma che aveva ispirato quelle incredibili invenzioni che l’artista aveva eseguito l’anno prima di muoversi a Palazzo Madama nell’estate del 1597.

Caravaggio lavorava velocemente: Mancini scrisse a suo fratello Deifebo a Siena di un dipinto che l’artista aveva realizzato raffigurante il Giudizio di Nostro Signore, con dieci figure a grandezza naturale, in soli cinque giorni, e che aveva dipinto l’ambizioso Sdegno di Marte del Marte che castiga amore che lo stesso Mancini aveva ambito possedere, ma che fu invece acquistato dal Cardinal Del Monte.

Le restanti ‘opere Vittrice’ non sembra fossero accessibili ai connoisseurs a Roma, anche quando furono ereditate da Girolamo Vittrice; poi passarono al figlio Alessandro, Governatore di Roma e dopo la morte di questi, avvenuta nel 1650, alla sorella Caterina la quale li vendette prontamente ad Olimpia Aldobrandini, che aveva sposato il principe Camillo Pamphilj nel 1647, e dopo che furono appesi per un breve periodo nel Casino del Belrespiro a Villa Pamphilj, arrivarono a Palazzo Aldobrandini al Corso, dove sono rimaste (con l’eccezione della Buona Ventura, donata a Luigi XIV nel 1665). Sembra però possibile che il palazzo di fronte alla Trinità dei Pellegrini fosse la destinazione originaria di questo rivoluzionario gruppo di dipinti che riflettono il gusto di qualcuno che aveva avuto un occhio acuto e tollerante. Le invenzioni che elaborò, come il Coridone, sono talmente idiosincratiche che sembrano provenire da un ambiente culturale completamente differente da quello cattolico.

Io credo che Caravaggio abbia realizzato nelle stanze prestategli dal Petrignani i dipinti privati come il Coridone, e l’Amore Vincitore Quest’ultimo rimase nelle mani dell’artista fino a che non fu acquistato da Benedetto / Vincenzo Giustiniani, dopo che iniziarono a collezionare l’arte moderna nel 1600.

Clovis WHITFIELD Umbria 3 aprile 2022 (traduzione di Consuelo Lollobrigida)

NOTE