di Clovis WHITFIELD

Landscapes by Domenichino and the Agucchis.

The development of the landscape medium that Domenichino came to epitomise has been difficult to disentangle. Traditional attributions are frequently unreliable, for when it was invented it was a secondary element in a workshop that was still known as a Carracci business even after the last family member had died, and the compositional devices to accompany a story with small figures had been largely invented by Agostino Carracci as the teacher / manager of the firm, while the fame of the whole operation would be claimed by his younger brother, whose own pictures with this subject-matter bore little relation to the forms that characterised the new landscape idiom. The pictures themselves were usually part of a larger decoration, but the enthusiasm shown for them as separate paintings gave them a new life when the interiors were dismantled, and they moved on with the attribution to the name of the business that was responsible for the whole interior.

Domenichino, an obsessive student of the academy in Bologna where Agostino was the principal teacher, took it upon himself to extend the idiom of ‘landscape with small figures’ when he came to Rome, and achieved acclaim for this speciality particularly among an intellectual patronage that saw this use of narrative as a practical medium for expression of their own musings, something that would have a wide success as the century advanced. But as a painter his ambition was much more wrapped up in history painting on a grand scale, and the majority of his exercises in the genre date from the early years of the century, before he could command a patronage separate from the Carracci team that he belonged with. The course of his own landscapes was not just confused by the early date traditionally given to the landscapes of the Stanza del Partnaso at Frascati, which Spear recognised as dating instead from 1616/18 (and actually executed, so far as the landscapes were concerned, by his compatriot Viola), but also by the tendency to spread the surviving paintings through his Roman career. Firm attributions, like that of the Landscape with Silvia and the Satyr in Bologna (which is by Agostino Carracci), the Oberlin Flight into Egypt (which turns out to be a later derivation probably by Grimaldi) and of the Prado Triumphal Arch (actually by Francesco Brizio) were difficult to reconcile with other paintings actually by Domenichino. The Aldobrandini lunette of the Flight into Egypt, a work that illustrates[1] the key role he played in shaping the ‘classical landscape’ associated with the Bolognese, was instead wishfully attributed in modern times to Annibale. But the main anomaly consists in the failure to realise that Domenichino had a gifted assistant who was able to collaborate with him on many of the paintings that have figured prominently in his catalogue with his name as the sole author. When they were taken out of their original context, these productions were routinely attributed to the name of the firm of Bolognese artists hired to do the whole decoration. Not only did the special qualities that Viola brought to the landscape idiom that Domenichino pioneered get lost along the way, even the work of the former’s own pupil Pietro Paolo Bonzi would be identified as Domenichino‘s own because of the compelling association of these little history paintings with a naturalistic landscape with their original inspiration.

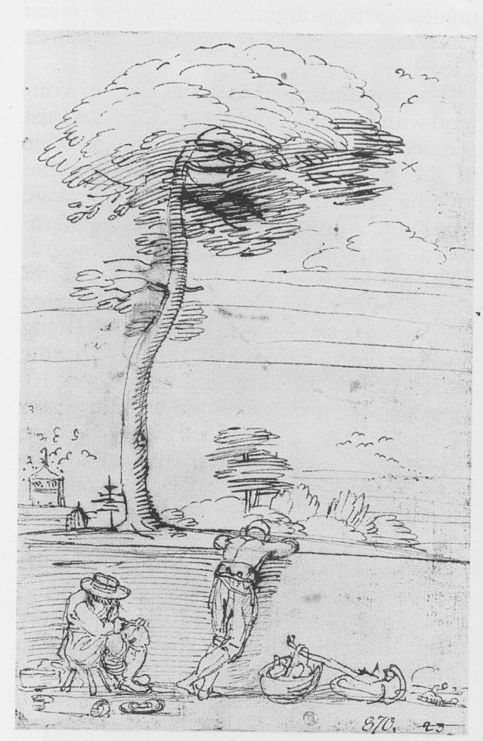

Among Domenichino’s earliest landscapes, those painted before he took part in the series of lunettes originally in the Palazzo Aldobrandini al Corso, there are both history subjects and ones where the subject is decorative but the figures are shown to be pursuing activities that marked these pictures as something special for the patrons who acquired them. Perhaps the first of these was the Landscape with Washerwomen, now in the Louvre, which Mancini (and Bellori) described, and said was bought by Annibale Carracci himself, and indeed it is one of the paintings that remained among his meagre possessions at the time of his death in 1609. It was unusual for a landscape subject to be peopled with characters showing azzione, and Annibale is said to have declared that he had not even paid the price of the likeness of the little boy who had spilled an amphora of wine in the stream, staining it. It is a fascinating painting, with a compositional arrangement that will become quite familiar in the Seicento, and a landscape that is carefully measured in perspective, with little figures calibrated according to their distances, many devices of alternating light and shade, recurring banks and stretches of water, a central building with a bridge set in front of a hill with a wooded bluff, seagulls hovering against the darker background, a flock of sheep on the far meadow, differing profiles of tree against the sky, and distant mountains whose blue peaks show that they are a good way away. The stream starts with a waterfall to the left, and is in a different plane than the stretch of water behind it, with a couple of boats giving another key to distance. But the central figures are meaningful, even though they are but washerwomen, the righthand one stands on tiptoe to take the basket of laundry she will wash on the board behind her. This was a subject that appealed to Annibale, who himself had done nothing of this kind since he had been in Bologna, and with that seal of approval the young man was to go far. We are fortunate in knowing quite a variety of landscapes by him that date from these first years in Rome, and they reveal an aspiring talent that was anxious to do something different from his colleagues, that would please the powerful patrons to whom he had an introduction. Some of these were decorative and probably from interiors where they would have been framed by architectural motifs, grotesschi and caryatids, but Domenichino tended to concentrate on interpreting narrative on a small scale, which found a ready appreciation from a new clientele that identified with his subject-matter.

The first documented landscape is the small copper with Abraham about to Sacrifice Isaac that has become better known since I published in the the exhibition England and the Seicento at Agnews in London in 1973, and which was painted in 1602 as it is already recorded in the January 1603 inventory of the Aldobrandini collection, drawn up by Mgr Gerolamo Agucchi, then maggiordomo to Cardinal Pietro. Although Bellori tells us that Domenichino spent two years, after his arrival in Rome, in Albani’s house the young painter must have been introduced to the Agucchi, soon after his arrival from Bologna and this was a new kind of history landscape that must have pleased the cardinal; it has a number of stylistic characteristics that make it a key piece of evidence in understanding the sheer application of this young painter, who gained the reputation of The Ox (il Bue) because of his hard work and determination.

Most of all it is the careful use of the landscape as a foil to the history subject, with the little figures assisting by gesture in the unrolling of the view as Abraham directs his son Isaac to the mountain top where would light the firewood that the young boy is carrying, in order to effect the sacrifice that God asked for in the Old Testament narrative (Genesis, 22). These are little figures, much the same proportion as in Agostino’s own painting (Paris, Louvre) that was presumably painted before his departure from Rome in the summer of 1600. We should bear in mind that Annibale’s own landscapes are without a history subject, and the idea of making it the setting for a narrative apart from the limited range of sacred stories was new.

Another history painting is the Landscape with St Jerome[2] in Glasgow, Museum and Art Gallery, is a prime example of his ability in the paese con piccole figure for which he gained fame in Rome almost as soon as he got there in 1602, this one with a real narrative theme. It was doubtless a private commission, done perhaps at the same time as his three fresco lunettes on the life of the same saint in the portico of Sant’ Onofrio on the Janiculum, which were commissioned by Gerolamo Agucchi. Like his brother Giovanni Battista’s request to Ludovico Carracci for a painting of Erminia and the Shepherds, where he saw himself escaping from the business world among shepherds, Jerome (in the lunette of the Temptation of St Jerome) reflects on his beguiling vision of dancing girls

(who figure in the background of the S. Onofrio fresco) and the delights of Roman life[3] as he suffers the loneliness of a hermit fasting in the midst of wild beasts and scorpions, as he writes to his patron Paula’s daughter Eustochium on the virtues of penitence and chastity.

The solace is in the prospect before us, and the beautifully crafted view into the distance, with many passages of receding banks, hillsides streams and lakes, peopled with wild animals and distant sailboats, is an idealised setting for Jerome’s penitence. When we see a drawing by Agostino Carracci of the same subject (Louvre. Inv. # 7117) it shows how Domenichino was the principal beneficiary of this kind of composition, and while his teacher had in fact done very few painted landscapes, he was the inventor of this kind of composition with a new naturalistic setting for the themes that the Seicento would propagate.

And the young painter’s drawn landscapes are in Agostino’s preferred medium of pen and ink, it seems to be later in his career that he used the softer lines of pencil and charcoal. The cliff that is a foil to the saint both in the fresco at S. Onofrio and in the panel in Glasgow is related to Agostino’s wooded bluffs that are featured in several of his drawings, and in the Sacrifice of Isaac on copper in the Louvre. Domenichino not only inherited the lessons of landscape design that he had had in the Accademia degli Incamminati in Bologna, he knew how to personalise a subject so that it would appeal to a patron.

Another landscape by Domenichino, one that belonged originally to a member of the Rondinini family was described by Bellori: “In casa Rondenini [sic] sopra una picciola tela di sua mano è finto un fiumicello, col Barcaiuolo, che spinge à riva, dov’ è una donna con una cestella di granchi, la quale piegata à terra, addita un fanciullo piangente, morso da uno di quei granchi, che gli pende dalla mano. Dietro di essa un pescatore tiene un’anguilla per fargliela guizzar frà le spalle, e col ditto alla bocca, accena silentio ad una Signora, che col marito, viene à diporta al fiume.” Bellori, 1672 op. cit. pp. 356-7. Not known in the original to Richard Spear when he wrote his monograph on Domenichino, he recorded it from a copy then in a private collection in Albany, NY. The figures have their own action, although not apparently a story, with the fishermen bringing in their catch, and a child grimacing as a crab hangs from its hand. This Rondenini painting [4] has recently been at auction, and is in a private collection in the USA.

The poling boatman is a figure often found in Domenichino’s work, from the River Landscape presented by the late Sir Denis Mahon to the Pinacoteca Nazionale in Bologna, to the oarsman in the Calling of Peter and Andrew on the apse of Sant’ Andrea della Valle in Rome, which Domenichino painted between 1623-28. The buildings in the landscape are not the kind of huts from the Venetian lagoon preferred by Annibale (and derived from Titian and Campagnola) but buildings more reminiscent of the Castelli romani, and the clump of trees (with markedly different foliage) articulates the prospects on each side of the view. The perspective is facilitated by devices like the rider leading his horse to the water, partly obscured by the bank that he is descending, and by the proportionally receding boats in the stretch of water leading to the town: another boat is drawn up on land, yet another with a boatman mooring it in the arch, and further diminutive figures are seen against the walls of the town. The horsemen and shepherd and flock of sheep on the land side provide a complementary gauge of distance, but it is the main figures who are the key to the subject, and despite their small size, the narrative is telling, and like the Landscape with Washerwomen had its own fame that Bellori transmitted to us. Like the Louvre landscape, it has an improvised subject, entering around the sensation that the child experiences in being bitten by a crab, rather like Caravaggio’s Boy bitten by a Lizard, itself a very novel idea.

It was a genre that was usually characterised by collaboration, partly because this was the nature of the business, and no-one regarded it as a self-sufficient form of painting, because it was as yet seen mainly in the context of the decorative idiom practised by pittori doratori or decorators. It is fortunate that there a a number of references to early works by Domenichino that confirm his specialisation in this field, and are the basis for recognising his establishment of a genre of history paintings with small figures; but recognising originals from imitations was difficult from the start especially as the Carracci came to be thought of as a kind of generic style where no-one knew who had done what. While it is clear that the compositional framework of these pictures owes a lot to Agostino Carracci’s examples, particularly in the drawings that were obviously frequently brought out as examples to follow, the emphasis on narrative on a small scale was clearly one for which Domenichino gained a reputation, and which gave his early works appeal to new patrons. There are several instances of pictures that he did that display activities, both narrative stories and figures performing even strenuous motions, which we can associate with his earliest period in Rome. He was persistent and even obstinate in this chosen creative vein, and the association of figures with landscape features, watery prospects with buildings, crenellated castles, sailing boats. If we are right to see the muscular poses as stemming from his guidance from Ludovico Carracci in the Accademia degli Incanninati in Bologna where he received his training, we should look for the origins of formal landscape composition in that of Agostino. Works like Ludovico’s Flagellation at Douai, the series of painting of the Flight into Egypt done for Senator Bonfiglioli (La Barchetta), demonstrate Ludovico’s concern with understanding movement in the human form. Domenichino of all the pupils to come out of the Accademia degli Incamminati in Bologna had application, and contemporary references speak of his slow but determined character. For the composition of his landscapes we can see that the example of Agostino’s drawings was a key source, they show him as a teacher aiming to provide a complete composition, usually entered around a figure subject. It was this interest in figure subjects associated with a landscape setting, that characterised the decoration that was associated with the Bolognese artists in Rome.

The organised landscape prospect, arranged around the figure subject, was something that Agostino had frequently drawn, and Benedetto Morelli in his funeral oration for him in 1603 (also published by Malvasia) mentioned how he took his students out to sketch ‘alla villa’ so catering even for the decorative painter who might in this way cope with placing figures in a landscape setting – Domenichino in reality chose to make this a pitch for a speciality that would appeal to clients who would not just commission altarpieces, but even have paintings in their own domestic setting. But he was also sensitive to the idea of narrative on a small scale, expressing all sorts of action (azzione as Bellori called it)

and it was here that he listened to and observed Ludovico as much as his cousin Agostino. The enthusiasm the elder Carracci had for figures in motion, muscles stressed, conveying action rather than a static description, was what Domenichino picked up from the elder Carracci, and he did it once again on a small scale, as if there was a market for history subjects on a domestic scale. Mancini ci racconta ‘et essendo raccolto et abbracciato da Monsignor Agocchi, gli fu dato trattenimento in casa sua; et in quel tempo, ancor giovanetto, fece quell’ historie di San Girolamo che sono nel portico di S. Honofrio, e nel medesimo tempo fece in casa alcuni paesaggi di gran vaghezza e perfettione, che in simil sorte di pittura veramente eccedeva . And apart from the little Landscape with the Sacrifice of Isaac that is already recorded in the inventory of Cardinal Pietro Aldobrandini’s collection in January 1603, another magnificent Paesaggio con palazzo e festa in barca that evidently dates from the Agucchi period, has surfaced (published by this writer for an exhibition at Pienza. Museo Diocesano, 2012). While we read that it was a subterfuge by his brother of the painting of the Liberation of St Peter (now known only from the copy in its original location in San Pietro in Vincoli) that revealed the excellence of there young Domenichino to Gerolamo Agucchi, it does seem that the elder brother had quite a lot to do with him from the start, and the January 1603 Aldobrandini inventory was in reality drawn up by him in his role as maggiordomo to Cardinal Pietro, and it was probably he who was the Monsignor Agocchi that Mancini referred to.

Instead of mere staffage he represented figures in action, boatmen poling, fishermen pulling nets, washerwomen kneeling at their laundry in the stream, hunters shooting, a horseman tending his mount, huntsmen with dogs. One of the first must be the Landscape with Washerwomen and Hunters in the Ackland Art Centre, Chapel Hill, which is first recorded in the collection of the Earl of Bridgewater in the eighteenth century, and must have been one of the genuine Domenichinos (as opposed to the many imitations) that came to England in the ages of Gavin Hamilton and the Rev. Holwell Carr. Although the composition is dominated by a hill with fortified buildings, in the distance, the framing motif is not the tree at the right side of the Louvre Landscape with Washerwomen, but an escarpment on the left, with the tree placed off centre in the near foreground, an arrangement that is a common denominator in many Domenichinesque landscapes. The figures are all strenuously occupied with various tasks, and are in at least six planes, from the washerwomen in the foreground to the riders with dogs hunting deer in the far background.

The figures are all doing tasks that are challenging to represent – from the couple crossing the stream, the man lending his arm in support of the woman balanced on the plank the fishermenpulling in their nets, their helpers on land pulling them to shore, the woodsman chopping with his axe, the washerwomen passing their load while the other is kneeling to wash the clothes in the stream. All are united with a carefully thought out perspective, with the central water feature being reinforced with a secondary pool in the background, and recurring banks so that some of the figures, and the donkey, are placed strategically behind into to convey recession. The building across the water was almost a trademark of this new classical landscape, and gave a far more familiar keynote than the alpine views and elaborate port scenes that Northern competitors made fashionable, using features that were essentially fantastical. Domenichino is here a pioneer in the framework of a landscape with figures, and it was a discipline that had immediate success – with artists because they got to see how perspective could be applied to natural features, and with patrons like the Agucchi brothers who could relate to the narrative of a figure subject in a natural setting. His landscape structure here is usually essentially similar, as the fresco he painted in the Casino Ludovisi in 1621, just as the Landscape with a Fortified Building now in the National Gallery is an echo of the Aldobrandini lunette of the Flight into Egypt. Domenichino was however more interested in becoming a successful figure painter, and although the discipline that he elaborated was a very successful part of ‘Bolognese’ decoration in Rome, he was more impressed with his own success as a history painter and was content to share the creative landscape speciality with others among the Bolognese contingent in Rome. But just as the apprentice in the sixteenth century learnt to draw anatomy from life so that when he came to create a painting he had no need for a model, being able to work entirely from his imagination, so Domenichino worked on the complete poses of many figures in movement so that he could essentially represent any narrative without any need to study them further. Bleary summed it up when praising his viva efficacia di esprimere gli affetti che fù suo proprio , destando i moti e movendo i sensi (1672, p. 290).

The Ackland painting is almost a demonstration piece, animating the people in the landscape who might otherwise, in saleroom parlance, be seen as ‘passing the time of day’. But it is interesting that the accentuated musculature is such a recognisable characteristic in this painting, as it will also be in works like the kneeling Narcissus in the Palazzetto Farnese fresco, the bystanders moved to take their shirts off in the Landscape with the Baptism in the Jordan (Zurich, Kunsthaus), the same subject in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, or the bather on the left of the little landscape in the Prado. It is interesting that Richard Spear regarded the Ackland painting as the copy, preferring the version at Christchurch, maybe because he was impressed also with the more suffused character of the Oberlin Flight into Egypt, that the museum bought on his advice in the 1970s. The Oxford painting is equally much more in character with the later imitations of Domenichino’s early landscapes, and no-one was better placed to produce them than Grimaldi who a generation later saw himself as the true successor of the ‘Bolognese’ landscape genre, and sought out early examples at a time when his French patrons were determined to secure examples of what had become a trendy decoration.

The Ackland painting is also key to understanding the authorship by Domenichino of the little Landscape with the Rest on the Flight into Egypt formerly in the collection of the late Mrs T.G. Winter, which has often been called Annibale (it was loaned to the 1962 Ideale Classico show in Bologna), and whose oldest history dates back to William Young Ottley who bought it from the Corsini collection in Rome[5]. Instead of a watery prospect, the subject figures are here the centre of a landscape that alternates from one side to the other, with lesser figures like the man lading the horse, the two men partly behind a bank in the middle distance, as well as the grazing donkey being close to their counterparts in the Ackland painting. They are scattered too in one of the most famous of Domenichino’s early landscapes, the Ford (Il Guado) in the Galleria Doria Pamphilj. which has a measured prospect over the water, punctuated by figures in boats leading the eye to the picturesque buildings in the background. This is the same kind of articulation as is to be found in Domenichino’s little Landscape with the Rest on the Flight in the Musée Mandet, Riom, one of the many Bolognese lands apes that made its way to France in the 17th and 18th centuries. It is right to see a correspondence in these details, as also in the buildings that are painted identically in the Louvre Landscape with Washerwomen., and the straining oarsmen who people these streams (or the one that is clearer in profile in the Palazzetto Farnese Death of Adonis). Although this is generally dated much later, it seems to me that that the Doria picture may well also be quite early, and actually correspond with the other landscape that is listed in the Aldobrandini inventory of 1603. The arrangement of the figures is a classic Agostino device, the diagonal placement on each side drawing the eye toward the rest of the landscape, whose harmonious recession is as carefully orchestrated as the view behind the Holy Family in the Winter picture, or the two Palazzetto Farnese frescoes.

The panel Paesaggio con palazzo e festa in barca (52 by 71 cm, Private Collection) ) which I published on the occasion of its exhibition at the Museo Diocesano in Pienza in 2012, is another of the genre of paese con figure piccole, most likely one of those that Mancini recalled when he said ‘e nel medesimo tempo (when he was staying with the Agucchis) fece in casa alcuni paesaggi a olio di grande vaghezza a perfettione, che in simile sort di pittura veramente eccedeva’. It is worth saying that these small paintings are of a different destination to the larger compositions that Domenichino and others did as members of the Carracci school in Rome, for more decorative destinations, and they were obviously regarded as something special. Like the Kimbell Landscape with Abraham about to Sacrifice Isaac, this is painted with meticulous attention to detail, and one can almost hear Giovanni Battista Agucchi asking, as he did in the context of the Erminia and the Shepherds, ‘ E per far il paese al più naturale, che fosse possible, sarebbe ben di mettersi delle palme de platani, sicomori, lentische, serrebenti, genebri, ole qualcheduno di più domestici. che ulivi, alori, quercie, e frassano, e pomo, e fichi, ma perché non potrebbero ne discernersi tutti basteria più facili da riconoscersi, come le Palme, i Platani, e pieni i Olivi, e Alori’ [6]. The passage is testimony to Agucchi’s ability as a landscape gardener, and indeed the palazzo itself is reminiscent of the Villa Aldobrandini at Frascati, where he worked with his patron Pietro Aldobrandini to direct the lavish fountains at the Teatro delle Acque that were being installed in 1603 by Ippolito Buzzi.

The landscape background, finely defined with a crenellated castle in the middle distance, is closely comparable to that of the Kimbell painting, which we know was painted in 1602, and the figures are characteristically full of movement and life. The figure leaning against the foreground wall recalls one of Agostino’s pen and ink drawing in Stockholm, while the fishing net once again recalls Agucchi’s request for such a feature in the Erminia and the Shepherds he wanted ‘et apogiata ad un’ degli alberi stasse una rete da pescare’. As for the boating party that is evidently reminiscent of the well-known drawing [7]in Cleveland, (traditionally called Annibale) which was used again by Domenichino for the same feature in the ex- Mahon River Landscape now in Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale. As I will argue in a forthcoming article on Agostino Carracci, this is a characteristic work of this artist, and it demonstrates how close the young Domenichino remained to the work of his teacher in the early years in Rome. But Domenichino makes the figures his own, all with things to do, like the child running towards its mother, the gard ener saluting as he emerges from the pergola, the fisherman about to launch his net, the musicians playing as they reach the dock.

The little boy Isaac in the Kimbell painting is a close companion of the figures with their backs to us leaning against the wall. The figures are all carefully studied, and have rightly been compared with those of the Landscape with a Boating Party, from the Mahon collection and mow in the Pinacoteca Nazionale, Bologna. This also has a central perspective, but provided by the the river on which the boats are set in alternate distances, and we can appreciate the care with which each of the figure groups, set diagonally in relation to the central vanishing point, are proportioned so that it is a fascinating combination of human activities in a natural setting. This was what Passeri described when he said that the artist ‘procurò d’erudirsi della perfetione della buona symmetry dell’ Ottica e della prospettiva, tanto necessaria a chi desidera collocare saggiamente e a suo luogo le figure in un copioso componimento e saperlo distribuire regolatamente in un piano’. The Agucchis will have admired the variety of foliage, and the reflections in the water, the banks covered with rushes and bushes seen against the lighter setting of the water ‘le ripe coperte di frasca, e verde erbetta con qualche cespuglio, overo arboscello, come Tamarisco, Saliceneri, e canne‘ as Giovanni Battista wrote in his programme for Erminia and the Shepherds. The art of composing these sophisticated landscapes was elaborated by Domenichino from his original lessons he had from Agostino in Bologna, and would form the basis of a tradition taken up with particular attention by other Bolognese hands, but especially by Nicolas Poussin after he arrived in Rome. It was not an apprenticeship in the traditional sense, but a skill that required the knowledge that was inherent in this new genre, and one of the many aspects of painting that the French painter studied attentively in order to have this skill.

Although there are relatively few of these landscapes with small figures, which clearly launched Domenichino to favour with the intellectual patrons who sustained him through his career, there are a few others that make a solid foundation to his early career, like the companion to the Mahon landscaper, Landscape with Hunters, now also in Bologna, Pinacoteca Nazionale, the pair formerly in the Colonna collection of Tobias and the Angel, (National Gallery, London) Moses and the Burning Bush (Metropolitan Museum, New York); the Landscape with the Calling of Peter and Andrew (on loan to Princeton University Art Museum) and its companion Christ and the Woman of Samaria (Wellesley College), the well-known Landscape with a Ford (Il Guado) in the Doria Pamphlilj Gallery in Rome, andthe Landscape with the Baptism in the Jordan formerly in the Cook collection and now in the Fitzwilliam Museum, Cambridge, not to mention the fresco over the door of the Farnese Gallery with the Virgin and the Unicorn. These were the intense masterpieces with which he launched himself on the Roman scene, and they precede the single contribution he made, as I have already argued, to the series of the Aldobrandini lunettes, painted for the upper segments of the chapel in the Corso from 1605 onwards. The Landscape with the Flight into Egypt is the single most successful design of the series, and although it was still a minor element in an obscure location, its adoption as a final work of Annibale Carracci, who no longer had the energy nor the inclination to devote himself to such a controlled design has deprived its real author of the credit for such a successful management of figures and their natural setting, while introducing a wholly uncharacteristic side of a personality who himself actually came to recognise the virtues of a genre that was quite at odds with his own genius. In many ways the lunette of the Flight into Egypt is a pivotal work, for although it is such a successful design, it was part of a decorative interior and as such it was a contribution to a genre where collaboration was the norm. Although there is no indication that the Doria picture itself is a work of collaboration, as Domenichimo became more successful and was in demand to undertake commissions for important patrons, Scipione Borghese who had him paint the fresco with the Flagellation of St Andrew for the Oratory of St Andrew at San Gregorio al Celio (1608) Vincenzo Giustiniani at Bassano Romano (1609) and Odoardo Farnese at the Abbazia di San Nilo at Grottaferrata, (1609/12) the major altarpiece of the Last Communion of St Jerome for S. Giroamo della Carità (1611/14), he was obviously more inclined to collaborate with other colleagues when it came to what was still considered a minor genre. For him it was the figures that really counted, and so even if the background landscape could be materially executed by others, the paintings maintained the attribution to the master who had contributed these important elements. And it can be said that the collaboration with his colleague Giovanni Battista Viola, who had come to Rome at the same period with his mentor Albani, was a most successful one, and he would have a really meaningful role to play in the development of the new landscape. But it was the early demonstration of little landscapes ‘di grande vaghezza e perfettione’ by Domenichino that Mancini admired chez the Agucchis that really started the tradition, and this is the point of this note.

Clovis WHITFIELD London December 2017

NOTE