di Clovis WHITFIELD

Caravaggio, from Prosperino to Finson and Vinck

Caravaggism is a unique phenomenon, the man represented a disruptive force in an industry the saw an exponential rise in production due to the inspiration of his example. We can see the proliferation of chiaroscuro pictures, the export of new imagery to the four corners of Europe, and many of these have very little to do with the technique that was at the foundation of this artistic revolution. Much of this activity was indeed attributed to Caravaggio himself, in the form of blame, when the idea of choosing subjects from life came to be thought of as evidence of his being unable to be creative or to use imagery as a vehicle for narrative, a kind of carelessness that started with still-life, tavern scenes, lowlife and sordid scenes and went on to paintings of battles and other iconography that has little to do with his work itself. But the promotion that his dealers and friends undertook, when he was present and active, has hardly been addressed, still less the extent to which the replicas and copies had the impact of the inventions themselves. It had the force of advertising, and the promotion generated even more attention than the artist could have done by himself.

For most of modern interest has concentrated on the few originals themselves, and not so much on their impact in their own time. The Caravaggesque is a phenomenon that starts, it would seem, more in the second decade of the century, with the host of Northern artists to whom the idea of painting directly (without conventional preparation or even apprenticeship) from life coincided with a generation of patrons who were struck by the possibility of visualising stories from the Bible as if they had happened in front of them. They were also struck by the force of capturing impressions of surfaces and materials, both new and old, rather than inventing such effects from their imagination. The vagaries of Caravaggio’s existence did not always allow him to complete a task, and there some hints that another hand – likely Prospero’s – is behind some details, like the carafe of flowers in the Corsini Portrait of Maffeo Barberini, the comb and ointment jar in the Detroit Martha reproving Mary for her Vanity, the violin in the Metropolitan Musicians, even maybe features like the carpet in the National Gallery Supper at Emmaus.

We now have Celio’s word that he saw Caravaggio painting a Lute Player in Orsi’s house, confirming the close relationship that existed between them, with Orsi acting as Caravaggio’s agent, promoter and provider of replicas. He and subsequent patrons played a part in steering his imagery which changed with a different requests and sometimes needed correction, even to make a subject recognisable.

But not so much attention has been given to the immediate interest generated in Caravaggio’s inventions, despite their wide distribution from a very early time. The numerous versions of some of the designs were not all done after the artist left the scene, and he must have been aware of this duplication, and even participated in it. Let us not forget that it was as a copyist he came on the scene in Rome, that he duplicated heads at ‘un grosso l’uno’ and that he was hired by Del Monte (according apparently to his earliest biographer, Gaspare Celio) because of his mimetic ability. And the early works, from the Boy peeling Fruit, and the Boy bitten by a Lizard, exist in multiple versions. There is evidently a possibility that some of the replicas done during Caravaggio’s period in Rome could have had some participation from the artist, and that some of the copies done by his agent Prospero were close enough to the pictures themselves to pass as originals. The difficulty of distinguishing the different hands is underlined by works like the ex-Barberini Lute Player, of which Claudio Strinati has recently spoken – https://www.aboutartonline.com/2018/01/29/claudio-strinati-dal-coro-caravaggio-ce-rivedere/ in terms that make it difficult to comprehend how it is featured in most of the modern monographs on Caravaggio as an original., while the enforced absence of the first version of the Capture of Christ has made it difficult to judge the rediscovered one in Dublin.

Caravaggio himself was associated more with the artisanal environment of the craftsmen belonging to the foundation of SS Trinità dei Pellegrini, rather than the more pretentious circles of the Accademia di San Luca. It was in this company that he encountered the champion of his peculiar talent for reproducing things accurately, Prospero Orsi, and it seems as though he needed some direction in order to be able to transform this ability, to apply the faithful replication of detail to new subjects, to portraiture and then to casually chosen forms, including those visible in the then revolutionary projected images from the camera obscura and the parabolic mirrors that enjoyed popularity at the time. The success of this change of focus was the realisation of a change of perception, from Caravaggio’s unprecedented ability in being able to create an image from the superficial features in front of him, rather than building one by imagination or recollection.

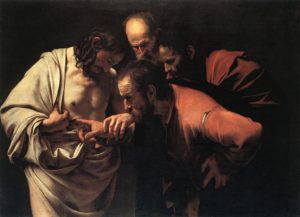

The results of this process were sensational, nothing like it had been seen before, for despite the illusionistic appearance of artificial perspective, there was nothing to prepare the viewer for such life-like imagery. Where these paintings were accessible, their likenesses were in demand, so much so that there are more than fifty known versions of the Incredulity of St Thomas. Prospero certainly did a version of it for the Mattei, as it is recorded in the family archive, and he was likely the author of the one that Cardinal Del Monte had. While Baglione says Caravaggio did the work for the Mattei, the main contender for the prime  version remains one that goes back to Benedetto Giustiniani’s patronage and is now in Potsdam.

version remains one that goes back to Benedetto Giustiniani’s patronage and is now in Potsdam.

He evidently took it, or a version of it, to Bologna, where he was Papal Legate from 1606 to 1611. We know that Prospero Orsi worked for the Mattei, and did versions of Caravaggio’s paintings – like the two Ambassador Béthune took back with him to Paris in 1605, of the Incredulity and the Supper at Emmaus. Before this it is clear that there were replicas of the latter subject, for the National Gallery Supper at Emmaus is clearly earlier than the painting that was painted for the Mattei and paid for in January 1602. It looks quite likely that Orsi also did a version of the Supper at Emmaus for one of the Mattei nephews in Palermo, Giovanni de Torres. This is the version now in the Galleria Regionale in Palermo, and it has many characteristics in common with the Béthune version now in Loches, suggesting that through Prospero’s agency these works were distributed through family connections and to important patrons, who clearly regarded them as representing Caravaggio’s work.

Not only was the Mattei Supper still in Palazzo Mattei long after Scipione Borghese’s death in 1634, but the original itself represented such a clamorous piece of illusionism – it a painting that belongs with the obsessively accurate naturalism of the pictures of 1597/98 – that it led to several replicas that Caravaggio may have done himself, or must at least have known because they came into existence during his stay in Rome. Apart from the Mattei version, which is untraced, Scipione Borghese evidently had two editions of the composition, of which the first is undoubtedly the painting in the National Gallery, and hung in Palazzo Borghese through the eighteenth century. Another was in his villa on the Pincio and Bellori seems to differentiate between the two, one being more tinta in his description (Vite, 1672, p. 208), and as the replica made – in all likelihood by Prospero – for Ambassador Béthune shows Christ bearded, this could show that it derived from the other Borghese picture. It looks as though Scipione Borghese acquired the National Gallery painting, which dates from well before his collecting experience (that started after the election of his uncle as Paul V in 1605) from a previous owner, and secured a second version probably through the agency of Prospero for the the walls of the Villa Borghese. This may have looked like the version of the composition known from the painting that passed through Sotheby’s, New York in 2005 ( Lot 559, Jan. 28, Lilian Rojtman Berkman Collection, 140 by 178,4cm) which shows Christ bearded. It may well be that Caravaggio collaborated with his promoter in producing versions of the Mattei paintings, where the realism was seen as a telling interpretation of the Gospel narrative that could be shared with privileged members of the family. Some of these duplicates must have been produced with Caravaggio’s participation, and he was not shy of exploiting an invention when it suited him, as the several versions of the Boy bitten by a Lizard or the St Francis in Adoration show.

In Naples Caravaggio seems to have found a sponsorship similar to that of Prospero Orsi, It seems likely that it was Louis Finson and his partner Abraham Vinck who offered Caravaggio refuge when he arrived in the city, gave him a place to work, and also found clients to purchase his paintings. The two Flemish artists were well established in Naples, with great social connections. Born probably in the early 1570s (his mother died in 1580), Finson’s Italian journey must have begun some time before he is recorded in Naples in 1604, i0n line with most of the Northerners who came to Italy, like his near contemporary Rubens (born 1577) who set out from Antwerp in May 1600, while Van Dyck arrived in Genoa when he was twenty-two. His partner in Naples was the Flemish merchant and painter Abraham Vinck (Antwerp c. 1575 – Amsterdam 1619) who settled in the city about 1600, married a Neapolitan – Vittoria Obechini – there and raised a family before going back to the Netherlands in 1610. This partnership meant that the two Flemish artists were already established in their career, and indeed they had a reputation as portraitists, copyists and agents: by 1608 they had a studio in Piazza Toledo in the centre of the city (the present Piazza Carità), next to S. Anna dei Lombardi for which Caravaggio painted three pictures in the Femaroli chapel,

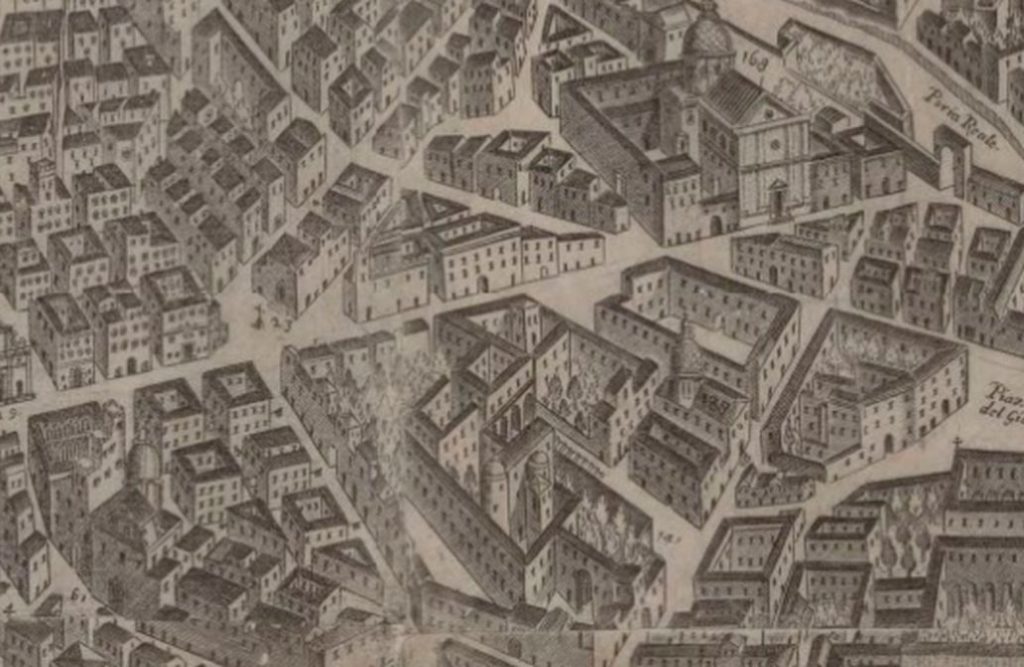

and just by the palazzo of Giambattista della Porta, the author of Magiae Naturalis and one of the most progressive scientists of the time; just beyond the church in Via Monteoliveto is Palazzo Gravina, where Ferrante Imperato had his Museum. [Detail from Alessandro Baratta’s Map of Naples, 1628: #23 is the Church (and Piazza) S. Maria della Carità, 188 is S. Anna dei Lombardi, behind it is Palazzo Gravina; 168 is the complex of Santo Spirito next to Porta Reale].

Their agency seems as fruitful as that of Prospero Orsi in Rome: the first Caravaggio they replicated was the Mary Magdalene, which Caravaggio is believed to have painted in Zagarolo. Even though he was a fugitive from justice and the revenge of the Tommassonis, his months there in 1606/07 were extremely productive, and he must have had good introductions as well as safe shelter as he painted major pieces like the Seven Acts of Mercy. It seems logical to assume that they were instrumental in an introduction to Alfonso Femaroli, for whom Caravaggio painted three paintings – the Stigmatisation of St Francis, St John the Baptist, and the Resurrection, for his chapel in the neighbouring S. Anna sei Lombardi (all lost in the 1805 earthquake). Among Finson’s clients was Niccolò Radolovich (A.E. Denunzio, Per due committenze di Caravaggio a Napoli, Nicolò Radolovich e il vicerè VIII conde-duca di Benavente (1603-1610) in Napoles y España Collecionismo y mecenazgo virreales en el siglo XVII, ed J.L Colomer, Madrid 2009, p. 175- 194) for whom Caravaggio painted a (lost) altarpiece. Other clients of Finson’s included Vincenzo and Tommaso de Franchis, for whom Caravaggio painted the Flagellation in San Domenico Maggiore, which was paid for in May 1607. Perhaps even more significantly he must have had a close relationship with the Viceroy, Duca de Benavente, who took away with him several Caravaggios when he left for Spain in July 1610.

Finson’s father was a decorative painter in Bruges, and would have been regarded as a pittore doratore in Italian practice, but both Louis’s brothers were painters too and there was less emphasis on the rigid guild distinctions that would have otherwise limited their activity as artists. But it is perhaps no coincidence that Louis’s chief profession was that of a portraitist, like that of his partner Vinck, ‘amicissimo del Caravaggio’ who evidently had a wide clientele in Naples, and they must have already achieved an established profession and style. The workshop included other assistants, like Andrea Perciabosco, and from 1611 probably Martin Faber, who continued to work with Finson in France. So it is possible to see different hands in versions of the same composition that originated in this studio. Vinck shared the ability to capture likeness, to copy from life or from other works of art, which was something that Caravaggio himself traded on, for he was taken on by Cardinal Del Monte for precisely this ability. Vinck dealt in antiquities but was also a painter of still-lives and market scenes, and although there is nothing documented of this activity it might be that the prominent still-life in paintings like Finson’s Adam and Eve in Marburg is by him. And it can seem as though the studio did turn out repetitions of some of the paintings produced there: there are other versions of the Viceroy’s Crucifixion of St Andrew that Finson had, there was a (untraced) version of the Madonna of the Rosary in Amsterdam, and several versions of Caravaggio’s Mary Magdalen. The two versions of the Judith and Holofernes, the subject of a Caravaggio that Frans Pourbus saw with the Madonna of the Rosary in what is evidently the Finson/Vinck studio in Naples in 1607 were evidently not far apart, as seems to be documented by their identical supports. Perhaps more significantly these merchants must have had a close relationship with the Viceroy,, who took away with him several Caravaggios when he left for Spain in July 1610: they included the Crucifixion of St Andrew (now in Cleveland Museum of Art). Finson was able to make copies of the painting, as many as three versions of it are known, including a version that was for sale in Amsterdam in 1619, from Finson’s estate, as an original Caravaggio. Like the copy of the Madonna of the Rosary that was for sale in Amsterdam in 1630, some of them undoubtedly were marketed with the attribution to Caravaggio, and the realisation that these copies are not all by the same hand points to the replication that went on in the Finson / Vinck studio. Another work done by Caravaggio for Benavente, the San Gennaro with the instruments of his Martyrdom, is known from Finson’s copy of it now in the Palmer Museum, Pennsylvania State University (bequest of Morton and Mary Jane Harris), while another work for him, a Christ Washing the Feet of the Disciples, is still unknown. This patronage however points to Finson’s (and Vinck’s) close links with the Spanish community in Naples, and we know that Finson was intending, when he left Rome for the South of France in 1613, to go on to Spain, where he evidently thought there was fertile ground for the new naturalism. There were already Caravaggios in Madrid, for the Conde de Villamediana had bought (as Bellori tells us) a ragazzo con fiore di melarancio in mano and the David with the Head of Goliath (now in Vienna, Kunsthistorisches Museum) where the Flemish composition under the painting points to a used panel that was made available to the artist in the same workshop. It is the privileged access that these Flemish merchants had to the works that Caravaggio produced during his months in Naples that strongly suggests that it was their studio that he worked while he was there.

Through these links we can begin to distinguish the business of promoting what was evidently a sensational innovation: both Prospero Orsi and the Finson / Vinck firm devoted the second part of their careers to exploiting the imagery that Caravaggio had invented. Wherever Caravaggio’s inventions arrived they had a tremendous impact, even when they were translations like Ambassador Béthune’s pictures, or Finson’s own creations like the Resurrection he painted in Naples and parted with in Aix-en-Provence. How much this promotion was done with Caravaggio’s participation is of course unclear, but some of it must have been achieved knowingly and in his presence.

Clovsi WHITFIELD London March 2018