di John T. SPIKE

Saint Francis of Assisi in Meditation by Caravaggio*

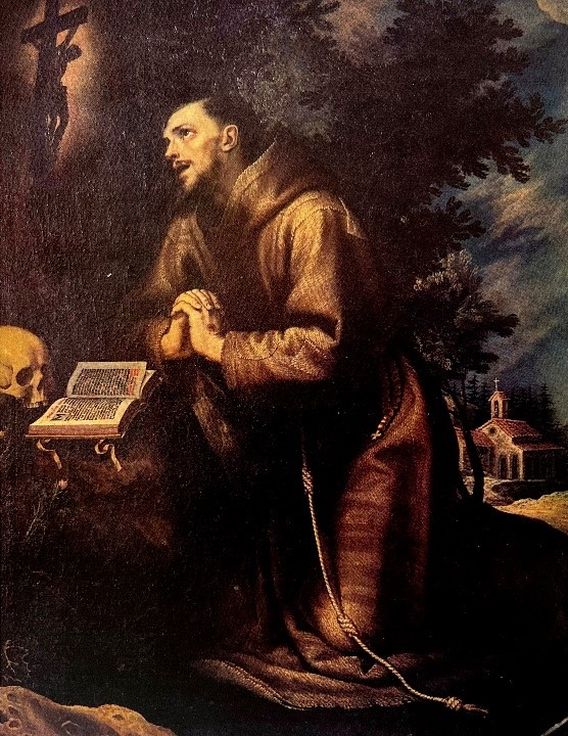

The Saint Francis in Meditation by Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio,[1] is widely recognized as one of the artist’s most spiritual paintings, and yet it remains one of his least studied (Fig. 1).[2]

As is often true of Caravaggio studies, the first recorded proposals as to the painting’s date and subject were voiced by the art historian Roberto Longhi. In his influential Ultimi studi sul Caravaggio…, 1943, Longhi dated the painting ‘all’ultimo e più affannato tratto della vita del maestro’.[3] Most scholars today agree with a late dating to the pivotal years of 1606 – 1607, when Caravaggio was a fugitive from Rome.[4] Longhi described this painting, which he considered a copy of a lost original by Caravaggio, as ‘forse un pensiero tragicamente autobiografico’ in which the saint seemed ‘in disperata meditazione sul Crocifisso’. Longhi’s interpretation has prevailed through the years without significant modifications by other scholars. On the other hand, it seems more likely that Caravaggio has depicted Saint Francis’s meditation as fervente, rather than disperata.

In this brief essay, I shall attempt to demonstrate that several unusual details in this painting represent Caravaggio’s efforts to visualize the spirit and teachings of Saint Francis. Probable sources for his knowledge of Franciscan ideas will be cited herein, including the epitaph of the saint’s tomb in San Francesco, Assisi, 1128; the biography and other writings traditionally ascribed to Saint Bonaventure (1221-1274); the Capuchin Constitution of 1536, and, finally, the Pauline Letters to the Corinthians and the Galatians, which are known to have influenced Francis deeply.[5]

My research in Franciscan iconography has been guided by the exegetical studies of two important Franciscan paintings of the 15th and 16th century: Giovanni Bellini’s Saint Francis in the Desert,[6] c.1475-78 (Cfr John V. Fleming, 1982),[7] and Caravaggio’s The Ecstasy of Saint Francis,[8] c. 1595, (Cfr Pamela Askew, 1962).[9] One of the crucial insights made independently by Askew and Fleming is the significance of even the smallest details in Franciscan paintings, evidently because the painters believed that Saint Francis viewed the world in this way. Through studies of these motifs in comparison with the writings of the Apostle Paul and Saint Bonaventure, in particular, Askew and Fleming were able to demonstrate that Bellini and Caravaggio deliberately informed their paintings of Francis with visual references to Franciscan ideas that were far more familiar to audiences in their time. It is also true that the writings and spiritual legacy of Saint Francis can be considered from more than one point of view, as has been true from the moment of his death in 1226. The Poverello d’Assisi combined an exalted elevation of thought with a uniquely picturesque mode of speech — as, for example, in his personification of “Sister Death” in the Canticle of the Sun, composed shortly before his death.

The scholar John Fleming drew upon texts and poems from Saint Bonaventure as a guide towards interpreting many heretofore overlooked details in Giovanni Bellini’s world-famous painting of Saint Francis in the Desert in the Frick Collection, New York. As an expert in medieval literature, Fleming was not seeking a specific text for these motifs, as art historians do, but, rather, he had concluded that “two great artists, one a poet and one a painter” (Bonaventure and Bellini) shared a “vocabulary of scriptural images in their meditation on the Franciscan Mystery.” With this approach, Fleming found that Bellini had composed his masterpiece with an “image by image” compilation of sacred ideas.[10] A similar pattern of interacting messages is detectable in Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Meditation, which is the subject of this article.

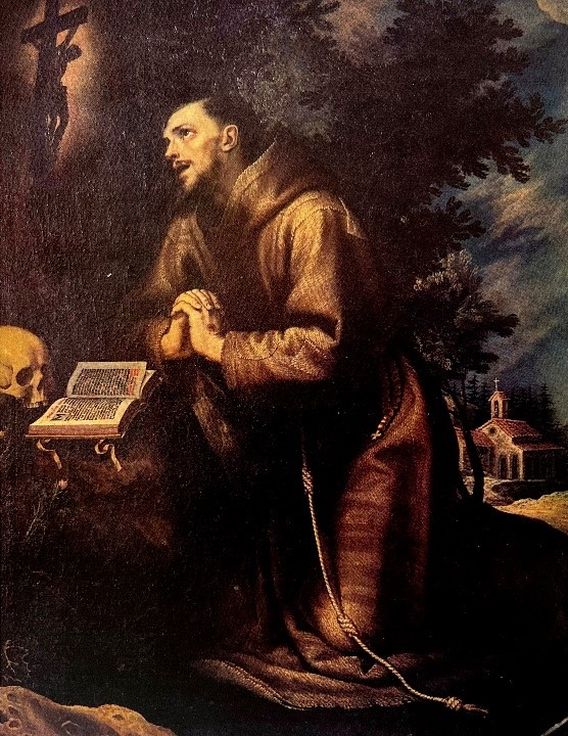

Some years before Fleming, Pamela Askew had independently arrived at nearly the same method in her exegesis of Caravaggio’s early painting of Saint Francis in Ecstasy (Fig. 2),[11] c. 1595.

Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneum

Askew’s research was inspired by her observation that the representation of Saint Francis in a reclining position, supported by an angel, was unprecedented in Franciscan iconography. Although Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Ecstasy has often been identified as a depiction of the saint’s stigmatization on Mount La Verna, the six-winged seraph recorded in the literature has been replaced with a youthful angel, a symbol of Divine Love. It appears that Caravaggio departed from the customary iconography in order to introduce additional and overlapping Franciscan themes into his composition. As Caravaggio’s Saint Francis falls backwards in prayer, he receives his vision in a state of ecstasy rather than with the joy mingled with sorrow described in the early sources. Askew notes that Caravaggio’s innovations coincide with Saint Bonaventure’s description of Saint Francis ‘rapt in such ecstasies of contemplation that he was carried out of himself, while perceiving things beyond mortal sense”.[12] Furthermore, Askew suggests that Francis’s prostrate position and ecstasy are recognizable metaphors of his yearning for death to this world and spiritual rebirth in Christ through his ardent love: Caravaggio

“pictorially elucidates Francis’s experience through association with familiar Pauline imagery… and the self-death for both saints that conforms them to the Passion of Christ”.[13]

Askew cites a passage in the Apostle Paul’s Second Letter to the Corinthians (5: 14-15) as one that Caravaggio appears to have been visualized in his Francis in Ecstasy in the Wadsworth Atheneum. This and other Pauline texts will be compared below in our examination of Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Meditation (Museo Civico “Ala Ponzone”, Cremona).

14 For the love of Christ overwhelms us when we consider that if one man died for all, then all have died; 15 Christ died for us all, so that being alive should no longer mean living with our own life, but with his life who died for us and has risen again’. (II Corinthians 5: 14-15).[14]

14 l’amore del Cristo infatti ci possiede; e noi sappiamo bene che uno è morto per tutti, dunque tutti sono morti. 15 Ed egli è morto per tutti, perché quelli che vivono non vivano più per se stessi, ma per colui che è morto e risorto per loro. (II Corinzi 5, 15).

The earliest depictions of Francis of Assisi were made within a few decades of his death, and mainly concentrated on a pictorial narration of his life.[15] The altarpiece of the Bardi Chapel in the Basilica of Santa Croce, Florence, is a masterpiece of these incunabula of Franciscan imagery, in which the saint’s portrait is flanked by twenty scenes of his life and postmortem miracles.[16] By the end of the 16th century, the stories of Francis’s life, especially of the Stigmatization, were known throughout Europe and abroad; in Italy, leading artists such as Federico Barocci, Annibale Carracci, Ludovico Cigoli and also Caravaggio began to enlarge the iconography of Saint Francis of Assisi with compositions devoted to the saint’s spiritual experiences in prayer and meditation.[17]

In the Cremona canvas, Caravaggio represented Saint Francis in solitary devotion, immersed in the impenetrable darkness that was distinctive to this artist’s new and innovative style. Deep in thought, his forehead furrowed, the Saint kneels in a posture of meditation, his head and beard resting on his clasped hands. Francis’s gaze is steadily focused downward to a wooden crucifix carefully positioned on a book of Gospels. At left, a white skull is prominently placed on the same smooth stone ledge.

These three elements were often depicted in Renaissance and post-Renaissance paintings of Saint Francis of Assisi:[18] the crucifix and the book were traditional symbols of Christ and of Sacred Scripture, respectively, while the skull is a universal symbol of mortality, invoking the fragility of life and the inevitability of death. Caravaggio appears to have expanded upon simple tradition, however, by purposefully arranging the three symbols in a kind of Passion still life with a central focus on the Cross of Christ, in accord with Francis’s profound devotion to the crucified Christ.[19]

The artist’s positioning of the crucifix to hold the Bible open, with its cover resting on the skull, has no precedent in the centuries of Franciscan iconography. The Saint meditates on a crucifix which is made to seem synonymous with the book that lies open before him. Caravaggio arranged the sacred objects in such an unusual and prominent way as to challenge the viewer to decide whether this remarkable Passion still life is simply a display of his creativity, or if it has been purposefully configured to convey a message. Perhaps both these results were intended. The fact is, Caravaggio’s obsession with intense expressions left him impervious to superficiality. In the pictorial vocabulary of Western art, by depicting these Passion symbols as a frieze, overlapping and touching, the painter has unified them. And much more can be said.

This unusual juxtaposition of the sacred Cross on top of an open book strongly recalls the Franciscan motto, “Christ, poor and crucified, is our book” (“Cristo povero e crocifisso è il nostro libro”). This thought is known in varying forms,[20] often ascribed to Francis personally, for example, in two of his Sayings,[21] N. 32, Contemplation is to be Preferred to Study:

“Being asked by a certain Brother what book he considered the most useful and profitable for him to read, the Saint replied : ‘Read the book of the Cross, and do not indulge in vain and curious studies.’[22]

Another Saying states: N. 50 How great is the Consolation of the Perfect in Meditating on the Passion of Christ

“At a time when the Saint was oppressed with constant suffering, he was asked why he did not have something read to him to recreate his mind, wearied by such constant suffering. ‘Nothing, he replied, is so delightful to me as the remembrance of the life and Passion of my Lord, on which I meditate daily and constantly; and were I to live till the end of the world, I should never want any other book.’“[23]

Closer to Caravaggio’s time, this early recorded idea was ratified in the Capuchin Constitution of 1536, in which the friars were instructed

“not to carry with them many books, so that they can study the most excellent book, the Cross”.[24]

And indeed Caravaggio has represented Francis immersed in his reading of “the book of the Cross.” When we realize this affinity with the Franciscan text, we see how clearly the painter’s invention has expressed it: the Cross and the Book are intertwined and unified. The Cross is given precedence.

The particularity of Caravaggio’s “still life” with a crucifix, book and skull becomes evident when compared with a slightly earlier painting by Ludovico Cardi, called Cigoli, another leading painter of that time (Fig. 3).[25]

In the last years of the 16th century, 1598-99, Cigoli painted three versions of Saint Francis in Prayer before a Crucifix, in which the Saint is seen, full length, kneeling in adoration of the crucifix with a skull and an open book before him. In the background of each these canvases, Cigoli depicted a small chapel that recalls Monte La Verna. At least two of these canvases entered prominent collections in Rome, where Caravaggio very likely saw them; he knew Cigoli personally, as well. Indeed, Caravaggio’s painting follows the general outline of Cigoli’s influential precedent. However, even if Caravaggio knew Cigoli’s orderly, but inexpressive, arrangement of the crucifix, book and skull, he conspicuously improved upon it. As we have seen, Caravaggio’s intriguing Passion still life is incomparably more dramatic and more infused with a Franciscan meaning.[26]

Once our attention is alerted to look carefully at the details of Caravaggio’s composition, we can observe how he positioned the skull and the Saint’s face as two points of light in a triangle of darkness on the left side of the canvas. Indeed, the skull anchors this triangle and is the endpoint of a diagonal line that descends from the hollow tree in the background and passes through the Saint’s body. Caravaggio has distributed the shadows to make a visual correspondence between the Saint’s sunken, shaded eyes and the empty sockets of the skull.

As we have said above, a human skull is an age-old sign of humility and mortality, and has understandably always been read as such in studies of Franciscan paintings. And yet, while the themes of humility and mortality are inevitably present, and appropriate, Francis would not have viewed a human skull as only a sign of physical death, for the simple reason he did not view death as only earthbound mortality. And once again, it is reasonable to conjecture that Caravaggio was aware Francis’s thoughts about death and endeavored to visualize them in this portrayal of the Saint’s intense, but not suffering, meditations on the fundamental symbols of the crucifix/book and the skull. In his Canticle of the Sun,[27] usually dated to 1224, Francis sings of Sister Death as the portal to eternal heaven, the path for Christians to follow Christ to the Resurrection.[28]

And this lesson was clearly stated in the epitaph dictated by pope Gregory IX, his friend and mentor, on Francis’s tomb in Assisi.

“Before his death, he was dead; after his death, he lives” (“Ante obitum mortuus, post obitum vivus”).[29]

These words are usually credited to pope Gregory IX, who canonized Saint Francis in 1226 and was his friend for many years.[30] A similar phrase in the epitaph in Assisi responds to the saint’s view of the unity of death, the Stigmata and the Resurrection of Christ.

To the Seraphic , Catholic and Apostolic / Francis, eminent for his exalted Humility; / the Support of Christianity, / the Repairer of the Church; / whose Body, while neither dead nor alive, / received the Marks of Christ crucified. / The Pope, mourning, rejoicing, and exalting / at his new Birth by his command, his Hand, and his munificence, has erected this Monument 16 August 1228. Before his death, he was dead; after his death, he lives. [31]

V.S.C.A. (VIRO SERAPHICO CATHOLICO APOSTOLICO,

Francisci Romani celsa humiltate cospicui / Christiani orbis fulcimenti, / ecclesiae reparatoris. / corpori nec viventi nec mortuo, Christi crucifixi plagarum / clavorumque insignibus admirando. / papae novae foeturae collacrymans / laetificans, et exultans, / iussu, manu, munificentia posuit

Anno Domini MCC XXVIII. XVI. Kalendas Augusti / Ante. Obitum. Mortuus. Post. Obitum. Vivus.

Two passages from the Apostle Paul’s letters to the Corinthians provided the theological foundations for the Franciscan ideas cited here, “Sister Death” and the epitaph in Assisi, “Ante obitum mortuus, post obitum vivus”. As noted above, II Corinthians 5:14-15 had already been associated with Caravaggio’s earlier San Francesco in Ecstasy (Fig. 2), by Askew in a groundbreaking article of 1969. A comparable passage in I Corinthians (15: 21-22) is revealing for its relevance to our discussion of the significance of the skull for Saint Francis.

21 For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead came also through a human being. / 22 For just as in Adam all die, so too in Christ shall all be brought to life. (I Corinthians 15: 21-22)

21 For since death came through a man, the resurrection of the dead came also through a human being. / 22 For just as in Adam all die, so too in Christ shall all be brought to life. (1 Corinzi 15: 21-22)

This verse is possibly the source of the ancient tradition that Adam’s skull is the skull traditionaly represented at the foot of the Cross on Calvary. As there is ample evidence that Francis closely associated the skull with the Cross, it is reasonable to assume that he habitually identified images of skulls as specifically Adam’s.[32] Following the Apostle, it is reasonable to assume that Francis regarded Adam’s skull as a symbol of mortal death that opens the portal towards Resurrection through Christ.

In the last quarter of the 16th century, inscriptions of Biblical texts became a significant and influential addition to Franciscan iconography, especially through the paintings and engravings of the Carracci family in Bologna. Of particular interest to the present study are two examples of quotations from the Apostle Paul’s Letter to the Galatians. An engraving of Saint Francis, which is perhaps a copy by Francesco Carracci after his uncle Agostino Carracci, is inscribed in the margin:

Vivo autem, iam non ego : vivit vero in me Christus (Galatians 2:20): “But I live, and I am no longer: but Christ lives in me.”

In Annibale Carracci’s early painting, San Francesco penitente, c. 1585 in the Pinacoteca Capitolina, Annibale has represented looking down at a crucifix leaning on a skull. His stigmatized hands are pointed towards his chest as if he has just emptied his heart with a full confession. Inscribed on the book in the foreground, one reads: Absit mihi gloriari nisi in cruce domini mei, in qua est salus, vita et resurrectio nostra. This first nine words of this inscription are a motto of the Franciscan Minorites: an abbreviated variant of Galatian 6:14, which continues continues with the words: nostri Iesu Christi per quem mihi mundus crucifixus est et ego mundo. May I never boast except in the cross of our Lord Jesus Christ, through which the world has been crucified to me, and I to the world (Galatians 6:14).[33]

Non sia mai ch’io mi glori d’altro che della croce del Signor nostro Gesù Cristo, mediante la quale il mondo, per me, è stato crocifisso, e io sono stato crocifisso per il mondo (Galatas 6:14).

Annibale’s remarkable composition anticipates the Cremona Saint Francis in Meditation to such an extent that we may suspect that Caravaggio knew it. The quotation from Galatians 6:14 is valuable confirmation that Pauline Letters were considered as authentic interpretations of the themes and spirituality of Franciscan paintings.

A final observation can be made in the exegesis, image by image, of Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Meditation (Cfr Fig. 1). The hollowed out tree and branches with dry leaves in the background of Caravaggio’s painting is generally understood as a reference to Francis’s preferred sanctuary, the forested wilderness of the Sacro Monte della La Verna.[34] It has not previously been noted that Caravaggio has depicted an unusual hollow tree which was doubtless intended as a reference to Francis’s preferred sanctuary, the forested wilderness of the Sacro Monte della La Verna. A miraculous beech tree that is mentioned in the Little Flowers of Saint Francis.[35] While it was still alive, an apparition of the Madonna and Child was seen several times atop this tree, blessing the friars as they passed in Procession on the way to the site of the Stigmata. In 1607, Jacopo Ligozzi, an artist at the Medici court in Florence, climbed the rocky cliff of La Verna in order to make accurate drawings of the sacred places. Ligozzi’s drawings were engraved by Raffaello Schiaminossi and published in 1612 with texts by Fra Lino Moroni, provinciale dei Francescani osservanti, in a book entitled Descrizione del sacro monte della Vernia, Florence, 1612. A hollow tree similar to that in Caravaggio’s Saint Francis in Meditation is illustrated as The Venerated Beech Tree of the Madonna at La Verna. Faggio molto venerato dai Frati abitanti del Monte della Vernia. (Fig. 5).[36]

John T. SPIKE Firenze 30 Aprile 2023

*We are grateful to John T. Spike for his permission to post this essay, which was published in the Città di Vita, Bienniale della Basilica di Santa Croce in Firenze, Novembre-dicembre, 2022.

NOTE

[1] Oil on canvas; cm 130 x 90, Museo Civico ‘Ala Ponzone’, Cremona, inv. 234. Cf JT Spike, Caravaggio, 2nd revised edition with CD-ROM, New York and London, 2010, no. 61, pp. 208-211. For more recent bibliography, see Spike in Z. Dobos et al., Caravaggio to Canaletto, exh. cat. Budapest, 2013-14, no. 30, pp. 196-197.

[2] During his brief life, Michelangelo Merisi, called Caravaggio, (Milan 1571-1610 Porto Ercole), painted several paintings of Saint Francis of Assisi, four of which have been identified to date. Three of these paintings in this group have been extensively studied by art historians; they are the two versions of Saint Francis Meditating on a Skull, (Spike 2010, cat. nos. 9.1 (Carpineto, deposito Palazzo Barberini) and cat. 9.2 (Santa Maria della Concezione, Rome); and the Saint Francis in Ecstasy Consoled by an Angel (Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford; Spike 2010, no. 8); and the present Saint Francis of Assisi in Meditation (Museo Civico, Cremona; Fig. 1), The Saint Francis in Meditation in Cremona, which is the latest of the four, has received the least attention from scholars.

[3] R. Longhi, “Ultimi studi sul Caravaggio e la sua cerchia”, in Proporzioni, v. 1, 1943, p. 17.

[4] For this date, see M. Gregori, Caravaggio come nascono i capolavori, exh. cat., Firenze, 1991, p. 291. A Maltese provenance has also been proposed by Mgsr John Azzopardi, “Un ‘San Francesco’ di Caravaggio in Malta nel secolo XVIII, in S. Macioce, ed., Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio, 1996, pp. Rome, 195-211. Most recently, it has been suggested that the Cremona Saint Francis might have been made by Caravaggio for Monsignor Benedetto Ala, who was governatore of Rome (1604–1610) and the ancestor of the marchese Filippo Ala Ponzoni of Cremona. In a deposition of 1605, Caravaggio stated that Monsignor Ala had granted him permission to carry a sword. The following year, alas, Caravaggio used his sword to kill Ranuccio Tomassoni.

[5] Francis frequently cited the Pauline Letters in his writings. Saint Bonaventure, The Life of Saint Francis of Assisi, 1904, New York, Chapter IX, §3: “He regarded with the utmost devotion all the Apostles, and in especial Peter and Paul, by reason of the glowing love they bore toward Christ.”

[6] Giovanni Bellini, Saint Francis in the Desert, c.1475-78, Frick Collection, New York.

[7] J. V. Fleming. From Bonaventura to Bellini: An Essay in Franciscan Exegesis, Princeton University, 1982.

8 Caravaggio, The Ecstasy of Saint Francis, Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, CT. Cf. Spike 2010, no. 61, pp. 208-2011.

[9] P. Askew, “The Angelic Consolation of Saint Francis of Assisi in Post-Tridentine Italian Painting,”in Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes, 1969, Vol. 32, 1969, pp. 280-306.

[10] Fleming 1982, pp. 25 and 69.

[11] See Note 8 supra.

[12] Bonaventure, Life of Saint Francis of Assisi, Translated E.G. Salter, New York, 1904, Chapter 10, §2.

[13] Askew 1969, p. 288.

[14] Cf Askew 1969, p. 288.

[15] G. Kaftal, Saint Francis in Italian Painting, London, 1950, p. 22.

[16] A. Paolucci, San Francesco e il suo messaggio nella tavola della Cappella Bardi e nei dipinti di Giotto, in San Francesco visto e interpretato attraverso l’arte in S. Croce, Ciclo di conferenze, 2003, a cura di P. Antonio di Marcantonio, Rettore della Basilica di S. Croce, pp. 29-51; P. Scarpellini, Iconografia francescana nei secoli XIII e XIV, in Francesco d’Assisi: storia e arte, a cura di R. Rusconi, Electa, Milano, 1982, pp. 95-97.

[17] The contributions of Barocci, Carracci and Cigoli and other influential artists, are thoroughly discussed and illustrated in L’Immagine di San Francesco nella Controriforma, S. P. Valenti Rodinò and C. Strinati, eds., Calcografia, Roma, 1982.

[18] As well as many other saints, for example, Saint Jerome. Francis’s most distinctive attributes are of course the three wounds of the Stigmata, whose absence from the present painting means that the saint is portrayed prior about two years before his death. According to Bonaventure, Life of St Francis, 1262, it was during his meditations on Mount La Verna on or before the Feast of the Exaltation of the Holy Cross, September 14, 1224, that Francis received in his hands, feet and side the Sacred Wounds of the stigmata.

[19] Devotion to the Cross and the Crucified One were fundamental to Saint Francis from the moment of his conversion when he heard the voice from the Cross in the small, abandoned church of San Damiano in 1207. The early writers.

[20] A well known example is “Il Libro della croce di Cristo”. Cf La Civiltà cattolica, vol. 4, ottobre 1976, p. 11.

[21] The “Sayings of Saint Francis” (Apophthegmata Sancti P. Francisci) are usually attributed to Saint Bonaventure, his most authoritative biographer. Cf. J.T.H. Moorman, The Sources for the Life of S. Francis of Assisi, 1940, p. 12.

[22] Works of the Seraphic Father Saint Francis of Assisi, Translated by A Religious of the Order, London, 1882, pp. 190.

[23] Works of the Seraphic Father Saint Francis of Assisi, Translated by A Religious of the Order, London, 1882, pp. 198-199.

[24] Capuchin Constitution of 1536, Chapter 9, 121. Cf: J. Olin, The Catholic Reformation, Savonarola to Ignatius Loyola, New York, 1992, p. 175; Spike 2010, p. 334.

[25] Ludovico Cardi, il Cigoli (Cigoli 1559 – Roma 1613), Saint Francis in Prayer before a Crucifix, c.1598, cm 155 x 120

Galleria Nazionale d’Arte Antica, Palazzo Barberini, inv. n. 825, Rome.

[26] Francesco Villamena (Assisi c.1565 – 1624 Rome) was an excellent engraver, who came to Rome around 1596 and was admitted into the Accademia di San Luca in 1604. He made two engravings, unfortunately undated, of Saint Francis in Prayer before a Crucifix: Both prints are in the Museo Francescano, Rome, and are illustrated in L’Immagine di San Francesco nella Controriforma, 1982, nos. 108-109. Both of these prints display the crucifix, book and skull in close proximity or even overlapping. Without knowing their dates, the relationship between Villamena and Caravaggio cannot be determined. San Francesco penitente (No. 109) is sometimes dated to 1606, which suggests that it pre-dates Caravaggio’s painting. San Francesco in preghiera (No. 108) represents the crucifix held by the Saint in his hands on top of the open book, which suggests that Villamena saw Caravaggio’s painting in Rome and was influenced by it.

[27] Also known as Laudes Creaturarum (Praise of the Creatures) and Canticle of the Creatures.

[28] “Praised be my Lord for Sister Death from whom no living soul escapes. She brings the doom of endless woe to those who pass away in guilt of mortal sin. Blessed they who die in doing Thy most holy will. To them the Second Death can bring no ill.” The Canticle of the Sun, Works of the Seraphic Father Saint Francis of Assisi, Translated by A Religious of the Order, London, 1882, P. 148.

[29] Francesco Guadagni, De invento corpore divi Francisci ordinis minorum parentis, Prelis Rev. Cam. Apost. Rome, 1819, p. 113.

[30] By another tradition, this final line in the epitaph was added by Pope Innocent IV in 125l.

[31] Ante obitum mortuus, post obitum vivus.

[32] Saint Francis of Assisi once signed a blessing to Brother Leo with a small drawing of the Tau cross above a skull with a mountain below. On this ancient parchment, which is still preserved in Assisi, Brother Leo wrote: Similar modo fecit istrud signum thau cum capite manu sua. The words cum capite refer to the the skull found on Calvary beneath the Cross – by tradition, the skull of Adam. Cf Miscellanea francescana di storia, di lettere, di arti, Foligno, VI, 1895, p. 130.

[33] D. Posner, Annibale Carracci; a study in the reform of Italian Painting around 1590, London, 1971, vol. 2, p. 11. According to the Rev. Father Floriano da Morrovalle (Ibid., p. 11) , the second part of the inscription is from the liturgy of the Mass, namely the Introit for Holy Week, used until the recent liturgical reform.” s dwn from the liturgy of the

[34] Francis received a mountainous parcel of land in 1213 from Count Orlando Catani of Chiusi to use as a place of spiritual retreat. Deep inside the wilderness of the Casentino mountains, La Verna is covered with a forest of beech and fir trees.

[35] I Fioretti di San Francesco, Garzanti Editore, 1993, p. 150.

[36] This is the text assigned to this print: “Faggio molto venerato da i Frati abitatori del Monte della Vernia, mentre ancora / vegetava, o si conservava, perche sopra di lui fù vista più volte MARIA/ Vergine in modo di benedirli mentre andavano in Processione alle sacrate Stimate, ò vero neo modo che qui tenente/ GIESV bambino in grembo. ALSO EXPLAINS with letter keys to image: Frate che descrive à I Forestieri tal fatto.Fusto del Faggio alto braccia trenta. Grossezza del diametro braccia diciotto. Caverna dentro à tal Faggio dove coprivano cinque huomini.”

San Francesco d’ Assisi in Meditazione del Caravaggio*

Il San Francesco in meditazione di Michelangelo Merisi da Caravaggio[1] è ampiamente riconosciuto come uno dei dipinti più spirituali dell’artista, eppure rimane uno dei suoi meno studiati[2] (Fig. 1)

Come spesso accade per gli studi di Caravaggio, i primi suggerimenti sulla data e il soggetto del dipinto furono espresse dallo storico dell’arte Roberto Longhi. Nei suoi importanti Ultimi studi sul Caravaggio, 1943, Longhi data il dipinto “all’ultimo e più affannato tratto della vita del maestro”[3]

La maggior parte degli studiosi oggi concorda con una datazione tarda, negli anni cruciali del 1606-1607, quando Caravaggio era in fuga da Roma[4]. Longhi descrisse questo dipinto, che considerava una copia di un originale perduto del Caravaggio, come “forse un pensiero tragicamente autobiografico” in cui il santo sembrava “in disperata meditazione sul Crocifisso”. L’interpretazione di Longhi ha prevalso negli anni senza significative modifiche da parte di altri studiosi. Sembra invece più probabile che Caravaggio abbia raffigurato la Meditazione di San Francesco come fervente, piuttosto che disperata.

In questo breve saggio cercherò di dimostrare che molti dettagli insoliti di questo dipinto rappresentano gli sforzi di Caravaggio per visualizzare lo spirito e gli insegnamenti di San Francesco. Verranno citate le probabili fonti che sono all’origine della sua conoscenza delle idee francescane, tra cui l’epitaffio sulla tomba del Santo che si trova nella chiesa di San Francesco ad Assisi, 1228; la biografia e altri scritti tradizionalmente attribuiti a san Bonaventura (1221-1274); la Costituzione dei Cappuccini del 1536 e, infine, le Lettere Paoline ai Corinzi e ai Galati, che – com’è noto – hanno influenzato profondamente Francesco[5].

La mia ricerca nell’iconografia francescana è stata guidata dagli studi esegetici di due importanti dipinti francescani del XV e XVI secolo: San Francesco nel deserto di Giovanni Bellini[6], c.1475-78 (Cf John V. Fleming, 1982)[7], e ‘L’estasi di San Francesco’ di Caravaggio[8], c. 1595, (Cfr Pamela Askew, 1962)[9].

Una delle intuizioni cruciali, fatte indipendentemente l’uno dall’altra, da Askew e Fleming si ritrova nel significato attribuito ai più piccoli dettagli dei dipinti francescani, evidentemente perché i pittori credevano che San Francesco vedesse il mondo in questo modo. Attraverso lo studio di questi motivi e dal confronto con gli scritti dell’apostolo Paolo e di San Bonaventura, Askew e Fleming hanno potuto dimostrare che Bellini e Caravaggio hanno deliberatamente integrato nei loro dipinti su Francesco, con riferimenti visivi a idee francescane che erano molto più familiari al pubblico del suo tempo, anche se è vero che gli scritti e l’eredità spirituale di san Francesco possono essere considerati da più punti di vista, come è avvenuto a partire dal momento della sua morte nel 1226.

Il Poverello d’Assisi coniugava un pensiero sofisticato con un modo di parlare autenticamente pittoresco – come, ad esempio, nella sua personificazione di “Sorella Morte” nel Cantico di Frate Sole, composto poco prima della sua morte.

Lo studioso John Fleming ha attinto dai testi e dagli scritti di San Bonaventura per interpretare molti dettagli, finora trascurati, del famoso dipinto di Giovanni Bellini ‘San Francesco nel deserto’ nella Collezione Frick di New York. Da esperto di letteratura medievale, Fleming non cercava un testo specifico per questi motivi, come fanno di norma gli storici dell’arte, ma, anzi, aveva concluso che “due grandi artisti, uno scrittore e uno pittore” (Bonaventura e Bellini) condividevano un “vocabolario di immagini scritturali nella loro meditazione sul mistero francescano”. Con questo approccio, Fleming ha scoperto che Bellini aveva composto il suo capolavoro con una raccolta “immagine per immagine”[10] di idee sacre. Un modello simile di messaggi interagenti è rilevabile nel San Francesco in meditazione di Caravaggio, oggetto di questo articolo.

Alcuni anni prima di Fleming, Pamela Askew era arrivata, attraverso un percorso personale, quasi con lo stesso metodo, alla stessa conclusione nella sua esegesi del primo dipinto di Caravaggio, il San Francesco in estasi[11] (Fig. 2), c. 1595.

Hartford, Wadsworth Atheneume

La ricerca della Askew era stata guidata dall’osservazione che la rappresentazione di San Francesco in posizione sdraiata, sorretto da un angelo, non aveva precedenti nell’iconografia francescana. Sebbene il San Francesco in estasi di Caravaggio sia stato spesso identificato come una rappresentazione della stigmatizzazione del Santo sul monte della Verna, il serafino a sei ali descritto in letteratura è stato sostituito con un angelo giovane, simbolo dell’Amore Divino. Sembra che Caravaggio si sia allontanato dall’iconografia tradizionale per introdurre nella sua composizione temi francescani aggiuntivi e sovrapposti. Il San Francesco di Caravaggio cade all’indietro mentre prega e riceve la sua visione in uno stato di estasi invece che con la gioia unita al dolore, come descritto dalle prime fonti. La Askew osserva come le innovazioni di Caravaggio coincidono con la descrizione di San Bonaventura: un San Francesco rapito in una tale estasi contemplativa da estraniarsi da sé stesso, mentre percepiva cose al di là del senso mortale[12]. Inoltre, la stessa Askew suggerisce che la posizione prostrata e l’estasi di Francesco sono metafore riconoscibili del suo anelito alla morte in questo mondo e alla rinascita spirituale in Cristo, attraverso il suo amore ardente. Caravaggio illustra pittoricamente l’esperienza di Francesco attraverso l’associazione con le più familiari immagini paoline… e alla morte del sé per entrambi i santi che li conforma alla passione di Cristo[13].

Askew cita un passaggio della seconda Lettera ai Corinzi dell’apostolo Paolo (5: 14-15)[14] come quello che Caravaggio sembra aver visualizzato nel suo Francesco in estasi nel Wadsworth Atheneum. Questo e altri testi paolini verranno qui di seguito, confrontati nell’esame del San Francesco in meditazione di Caravaggio (Museo Civico, Cremona).

Perché l’amore di Cristo ci spinge, al pensiero che uno è morto per tutti e quindi tutti sono morti. Ed egli (Cristo) è morto per tutti, perché quelli che vivono non vivono per se stessi, ma per colui che è morto e risuscitato per loro” (II Corinzi 5, 15)[15].

Le prime raffigurazioni di Francesco d’Assisi furono realizzate entro pochi decenni dalla sua morte e si concentrarono principalmente su una narrazione pittorica della sua vita. Capolavoro di questi incunaboli di immaginario francescano, è la pala d’altare della Cappella Bardi nella Basilica di Santa Croce a Firenze, in cui il ritratto del santo è affiancato da venti scene della sua vita e dei miracoli post mortem[16]. Alla fine del XVI secolo, le storie della vita di Francesco, in particolare della stigmatizzazione, erano conosciute in tutta Europa e all’estero; in Italia artisti di spicco come Federico Barocci, Annibale Carracci, Ludovico Cigoli e anche lo stesso Caravaggio iniziarono ad ampliare l’iconografia di San Francesco d’Assisi con composizioni dedicate alle esperienze spirituali del santo in preghiera e in meditazione[17].

Nella tela cremonese, Caravaggio rappresenta San Francesco in devozione solitaria avvolto nell’oscurità impenetrabile che caratterizzava lo stile nuovo e innovativo di questo artista. Immerso nei suoi pensieri, la fronte corrugata, il Santo si inginocchia in una posizione di meditazione, la testa e la barba appoggiate sulle mani giunte. Lo sguardo di Francesco è costantemente concentrato verso il basso in direzione di un crocifisso accuratamente posizionato sul libro dei Vangeli. A sinistra, un teschio bianco è posizionato in rilievo, sulla stessa sporgenza di pietra liscia.

Questi tre elementi sono stati spesso raffigurati nei dipinti rinascimentali e post-rinascimentali di San Francesco d’Assisi:[18] il crocifisso e il libro erano simboli tradizionali rispettivamente di Cristo e della Sacra Scrittura, mentre il teschio è un simbolo universale di mortalità, evocando la fragilità della vita e l’inevitabilità della morte. Caravaggio sembra aver ampliato la tradizione disponendo di proposito i tre simboli in una sorta di natura morta della Passione con un focus centrale sulla Croce di Cristo, in accordo con la profonda devozione di Francesco al Cristo crocifisso[19].

Il posizionamento del crocifisso con la Bibbia aperta e la copertina appoggiato sul teschio, non ha precedenti nei secoli dell’iconografia francescana. Il Santo medita su un crocifisso che pare sinonimo del libro che gli sta aperto davanti. Caravaggio ha disposto gli oggetti sacri in un modo così insolito e con un tale rilievo come a sfidare lo spettatore a decidere se questa straordinaria rappresentazione della Passione è semplicemente un’esibizione della sua creatività o se è stata volutamente concepita per trasmettere un messaggio. Forse aveva in mente entrambe le cose. Il fatto è che l’ossessione di Caravaggio per le espressioni intense, ha fatto sì che non si fermasse all’aspetto superficiale. Nel vocabolario pittorico dell’arte occidentale, raffigurando questi simboli della Passione come un fregio, sovrapposti e tangenti come sono, il pittore li ha unificati. Si potrebbe aggiungere molto altro.

Questa insolita giustapposizione della sacra Croce sopra un libro aperto richiama fortemente il motto francescano: “Cristo povero e crocifisso è il nostro libro”. Questo pensiero è noto in varie forme[20], e spesso è stato attribuito a Francesco stesso, ad esempio, in due suoi scritti:[21] il N. 32, ‘La contemplazione è da preferire allo studio: «Interrogato da un confratello su quale libro ritenesse più utile leggere, il Santo rispose: ‘Leggi il libro della Croce, e non indulgere in studi vani e bizzarri.’[22] Secondo un altro scritto (N. 50) ‘Quanto è grande la consolazione dei perfetti nel meditare sulla passione di Cristo’: «In un tempo in cui il Santo era oppresso da continue sofferenze, gli fu chiesto perché non avesse qualcosa da leggere che potesse ricreare la sua mente, stanca di tanta sofferenza.

«Niente, mi rispose, è così delizioso per me come il ricordo della vita e della passione del mio Signore, sul quale medito quotidianamente e costantemente; e se dovessi vivere fino alla fine del mondo, non vorrei mai nessun altro libro».[23]

Più vicino al tempo di Caravaggio, questa prima idea fu inserita nella Costituzione dei Cappuccini del 1536, in cui si ordinava ai frati di «non portare con sé molti libri, perché possano studiare il libro più eccellente, la Croce».[24] E infatti Caravaggio ha rappresentato Francesco immerso nella sua lettura del «libro della Croce». Quando ci rendiamo conto di questa affinità con il testo francescano, vediamo con quanta chiarezza la creatività del pittore l’ha realizzata: la Croce e il Libro sono intrecciati e unificati. La Croce ha la precedenza.

La particolarità della “natura morta” di Caravaggio con crocifisso, libro e teschio diventa evidente se confrontata con un dipinto di poco precedente di Ludovico Cardi, detto il Cigoli, altro pittore di spicco dell’epoca[25]. (Fig. 3)

Negli ultimi anni del XVI secolo, 1598-99, Cigoli dipinse tre versioni di San Francesco in preghiera davanti a un Crocifisso, in cui si vede il Santo, a figura intera, inginocchiato in adorazione del crocifisso con un teschio e un libro aperto davanti lui. Sullo sfondo di ciascuna di queste tele, Cigoli dipinse una piccola cappella che ricorda il Monte La Verna.

Almeno due di queste tele entrarono in importanti collezioni romane, dove molto probabilmente le vide Caravaggio che conosceva personalmente anche Cigoli. In effetti, la pittura di Caravaggio segue lo schema generale dell’influente precedente di Cigoli. Tuttavia, anche se Caravaggio conosceva la disposizione ordinata, ma inespressiva di Cigoli del Crocifisso, del libro e del teschio, la migliorò notevolmente. Come abbiamo visto, l’intrigante natura morta della Passione di Caravaggio è incomparabilmente più drammatica e più intrisa di significato francescano[26]. Una volta che la nostra attenzione è sollecitata ad osservare i dettagli della composizione di Caravaggio, possiamo notare come l’autore ha posizionato il teschio e il volto del Santo come due punti luminosi in un triangolo di oscurità sul lato sinistro della tela. Il teschio, infatti, contiene questo triangolo ed è il punto finale di una linea diagonale che scende dall’albero cavo sullo sfondo e passa attraverso il corpo del Santo. Caravaggio ha distribuito le ombre per creare una corrispondenza visiva tra gli occhi infossati e sfumati del Santo e le orbite vuote del cranio.

Come abbiamo detto sopra, un teschio umano è un segno secolare di umiltà e mortalità ed è comprensibilmente sempre stato letto come tale negli studi sui dipinti francescani. Eppure, mentre i temi dell’umiltà e della mortalità sono inevitabilmente presenti e appropriati, Francesco non avrebbe visto un teschio umano solo come un segno di morte fisica, per il semplice motivo che non vedeva la morte solo come mortalità terrestre. E ancora una volta, è ragionevole ipotizzare che Caravaggio fosse consapevole dei pensieri di Francesco sulla morte e si sia sforzato di visualizzarli in questo ritratto delle intense, ma non sofferenti, meditazioni del Santo sui simboli fondamentali del crocifisso/libro e del teschio. Nel suo Cantico del Sole[27], solitamente datato 1224, Francesco canta ‘Sora Morte’ come la porta del Paradiso eterno; cammino dei cristiani per seguire Cristo fino alla risurrezione[28].

E questa lezione era chiaramente enunciata nell’epitaffio dettato da Papa Gregorio IX, suo amico e mentore, sulla tomba di Francesco ad Assisi. “Prima di morire, era morto; dopo la sua morte, vive” (“Ante obitum mortuus, post obitum vivus”)[29]. Queste parole sono solitamente attribuite a Papa Gregorio IX, che canonizzò san Francesco nel 1226 e fu suo amico per molti anni[30]. Una frase simile nell’epitaffio di Assisi, corrisponde alla visione del santo dell’unità della morte, delle stimmate e della risurrezione di Cristo.

Ai Serafici, Cattolici e Apostolici / Francesco, eminente per la sua esaltata Umiltà; il sostegno del cristianesimo, / il Riparatore della Chiesa; / il cui Corpo, mentre né morto né vivo, ricevuto i segni di Cristo crocifisso. / Il Papa, in lutto, gioendo ed esaltando / alla sua nuova Nascita per suo comando, la sua Mano, e la sua munificenza, ha eretto questo Monumento il 16 agosto 1228. / Prima della sua morte, era morto; dopo la sua morte, vive[31].

V.S.C.A. (VIRO SERAPHICO CATHOLICO APOSTOLICO, Francisci Romani celsa humiltate cospicui

Christiani orbis fulcimenti, ecclesiae reparatoris. / corporinecviventinecmortuo, / Christi crucifixi / plagarum / clavorumque insignibus admirando. / papae novae foeturae collacrymans / etificans, et exultans, / iussu, manu, munificentia posuit

Anno Domini MCC XXVIII. XVI. Kalendas Augusti Ante. Obitum. Mortuus. Post. Obitum.

Due brani delle lettere dell’apostolo Paolo ai Corinzi, hanno fornito le basi teologiche per le idee francescane qui citate, “Sora Morte” e l’epitaffio ad Assisi, “Ante obitum mortuus, post obitum vivus”. Come notato sopra, II Corinzi 5:14-15 era già stata associata al precedente San Francesco in estasi di Caravaggio (Fig. 2), da Askew in un articolo rivoluzionario del 1969. Un passaggio simile in I Corinzi (15: 21-22) è rivelatore per la sua rilevanza nella nostra discussione, del significato del teschio per San Francesco.

21 Poiché la morte è venuta per mezzo di un uomo, anche la risurrezione dei morti è avvenuta per mezzo di un essere umano. 22 Infatti, come tutti muoiono in Adamo, così anche in Cristo tutti saranno riportati in vita. (I Corinzi 15: 21-22)

Infatti, siccome per mezzo di un uomo è venuta la morte, così anche per mezzo di un uomo è venuta la risurrezione dei morti. 22 Perché, come tutti muoiono in Adamo, così tutti saranno vivificati in Cristo. (1 Corinzi 15: 21-22)

Questo passo è forse la fonte dell’antica tradizione secondo cui il teschio di Adamo è il teschio tradizionalmente rappresentato ai piedi della Croce sul Calvario. Poiché vi sono ampie prove che Francesco associasse strettamente il teschio alla Croce, è ragionevole presumere che identificasse abitualmente immagini di teschi come simbolo specifico di Adamo[32]. Seguendo l’Apostolo, è ragionevole presumere che Francesco considerasse il teschio di Adamo come un simbolo di morte che apre la porta verso la risurrezione, attraverso Cristo.

Nell’ultimo quarto del XVI secolo, le iscrizioni di testi biblici divennero un’aggiunta significativa e influente all’iconografia francescana, soprattutto attraverso i dipinti e le incisioni della famiglia Carracci a Bologna. Di particolare interesse per il presente studio sono due esempi di citazioni dalla Lettera ai Galati dell’apostolo Paolo. Un’incisione di San Francesco, forse copia di Francesco Carracci dallo zio Agostino Carracci, è iscritta a margine: Vivo autem, iam non ego: vivit vero in me Christus (Galati 2,20): “Vivo già non io, ma Cristo vive in me”

In un dipinto giovanile di Annibale Carracci, San Francesco penitente c. 1585, che si trova nella Pinacoteca Capitolina, Annibale ha rappresentato San Francesco che guarda un crocifisso appoggiato a un teschio. (Fig. 4) Le sue mani stigmatizzate sono puntate verso il petto come se si fosse appena svuotato il cuore con una confessione piena. Iscritto nel libro in primo piano si legge:”Absit mihi gloriari nisi in cruce domini mei, in qua est salus, vita et resurrectio nostra”. Queste prime nove parole di questa iscrizione sono un motto dei Minoriti Francescani: una variante abbreviata di Galati 6,14[33], che continua con le parole: nostri Iesu Christi per quem mihi mundus crucifixus est et ego mundo. “Possa io non vantarmi mai se non nella croce di nostro Signore Gesù Cristo, per mezzo della quale il mondo è stato crocifisso per me e io per il mondo (Galati 6,14).

La straordinaria composizione di Annibale anticipa a tal punto il San Francesco in meditazione di Cremona che si può sospettare che Caravaggio la conoscesse. La citazione di Galati 6,14 è una preziosa conferma che le Lettere Paoline erano considerate come autentiche interpretazioni dei temi e della spiritualità della pittura francescana.

Un’ultima osservazione può essere fatta nell’esegesi, immagine per immagine, del ‘San Francesco in meditazione’ di Caravaggio (Cfr Fig. 1).

L’albero scavato e i rami con le foglie secche sullo sfondo del dipinto di Caravaggio sono generalmente intesi come un riferimento al santuario preferito di Francesco, il bosco selvatico del Sacro Monte della Verna[34]. Non è stato notato in precedenza il fatto che Caravaggio abbia raffigurato un insolito albero cavo, che allude senza dubbio al santuario preferito di Francesco, il folto boscoso della Verna. Un faggio miracoloso è menzionato nei Fioretti di San Francesco[35].

Mentre era ancora in vita, in cima a quest’ albero è stata vista più volte un’apparizione della Madonna con il Bambino, che benedice i frati mentre passano in processione sulla strada per il luogo delle Stimmate. Nel 1607 Jacopo Ligozzi, artista alla corte dei Medici a Firenze, si arrampicò sulla rupe rocciosa della Verna per realizzare accurati disegni dei luoghi sacri. I disegni di Ligozzi furono incisi da Raffaello Schiaminossi e pubblicati nel 1612 con testi di Fra Lino Moroni, Ministro provinciale dei Francescani Osservati, in un libro intitolato ‘Descrizione del sacro monte della Verna’, Firenze, 1612. Un albero cavo simile a quello del San Francesco in meditazione di Caravaggio è illustrato come “Il venerato faggio della Madonna alla Verna”. (Figura 5)

[1] Per tutte le note successive, si rimanda al testo in lingua inglese, di seguito riportato

[17] »